The rough-and-ready fighting spirit of the Australians had become refined by an experienced battle technique supported by staff work of the highest order. The Australians were probably the most effective troops employed in the war on either side.

Major General John ORyan, US 27th Division

CONTENTS

A medieval town in ruins: the remains of St Martins Cathedral, Ypres, 8 October 1917. AWM E01117

FOREWORD

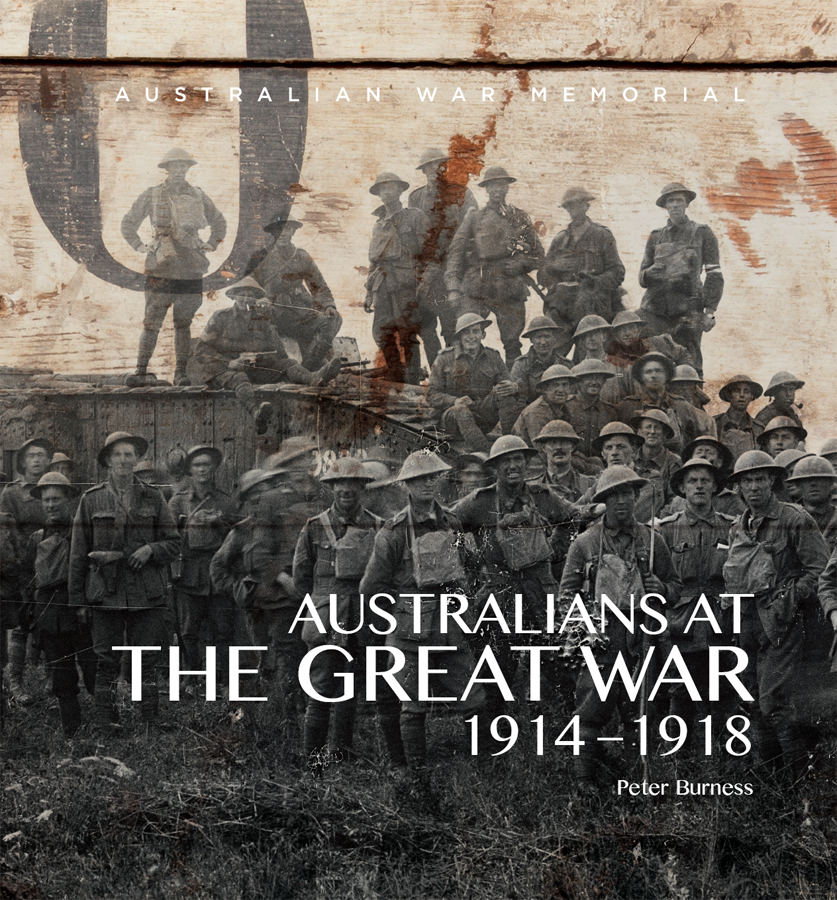

A century ago Australia became swept up in the First World War, and a period of commitment, physical stress, and emotional pain descended upon the nation. There had never been armed conflict on such a scale before, and it became known as The Great War. When it finally ended, four years later, the war left shattered nations, destroyed empires, ruined communities, displaced civilians, huge debt, and a terrible loss of life. Decades of grief and mourning followed in its wake.

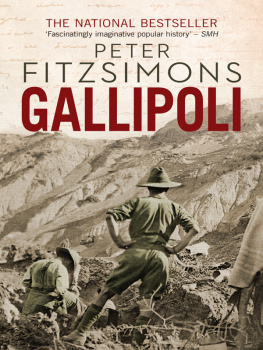

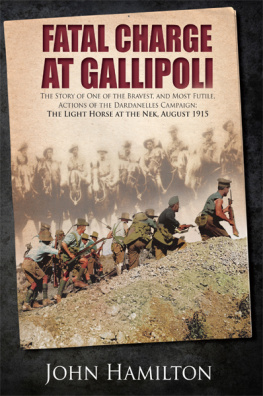

Australia was pledged to the allies cause right from the start. Most notably, hundreds of thousands of its citizens became soldiers, sailors, airmen or nurses for the duration of the struggle. They were all volunteers. More than 350,000 of them went off to serve on foreign battlegrounds, or in the air, or on far-off seas. On the shores of Gallipoli, the sands of the Sinai, and the muddy fields of France, they took part in some of the wars most famous battles, winning praise for their courage and irrepressible spirit. But the cost was high. Tragically, more than 60,000 failed to return; almost one in five of those who fought had been killed in battle, died of wounds, or succumbed to sickness or disease. Many of those who did survive would continue to bear mental and physical injuries.

The losses sustained by our young nation, and the stories of its countrymens suffering, their inspirational deeds, and their many brave achievements, ensured that Australias experience of the war became a dominant story in our history.

More than a decade has passed since the death of the last Anzac of the Great War. But that war remains with us still. It is not only present in the local memorials and the annual national commemoration of Anzac Day, but also in small rituals: the use of the poppy for remembrance, words in our language such as digger and Anzac, and the symbolism of the soldiers slouch hat. It is also seen in the many acts of remembrance, both public and private, in publications and other commemorative programs, and in the continuing pilgrimages to the former battlefields.

Australias First World War official historian and founder of the Australian War Memorial was Charles Bean. He landed with the Australian troops on Gallipoli and stayed with them at the front until the wars end. To conclude his final volume of the official history, he said this:

What these men did nothing can alter now. The good and the bad, the greatness and smallness of their story will stand. Whatever of glory it contains nothing now can lessen. It rises, as it will always rise, above the mists of ages, a monument to great-hearted men; and, for their nation, a possession for ever.

Australias national anthem calls on us as a nation to rejoice that we are young and free. We are also as a nation grateful for the legacy given us by these men and women, a legacy born of idealism and forged in bloody sacrifice.

Few people know more than Peter Burness about the role Australians played in the First World War. Australians at the Great War 19141918 represents the distillation of many years spent researching, and reflecting on, this important story. During the writing of this work Peter was generously funded by The De Lambert Largesse Foundation, and it is with deep gratitude that I acknowledge this support.

This highly illustrated book provides a clear explanation of Australias role in the battles of the Great War. It is a story that should never be forgotten. As Charles Bean observed, it is indeed our possession for ever.

Dr Brendan Nelson

Director, Australian War Memorial

AUSTRALIA JOINS THE WAR

Australia entered the twentieth century as a newly federated nation brimming with optimism and hopes of peace and prosperity, but it soon had to face a world war that brought four years of hardship, commitment, and terrible loss of life. In 1914, on the other side of the world, events in the Balkans and across Europe plunged the world into a dreadful international conflict that would change the course of history and leave a legacy of grief, debt, and waste.

Australia was a young, progressive, and largely urban nation. The population was still under 5 million. Most of its citizens maintained an interest in European matters and had a close affection for Britain. There was never a doubt that it would stand with the rest of the British empire in time of strife. Once Britain declared war on Germany on 4 August after its invasion of Belgium and France, Australia was committed too.

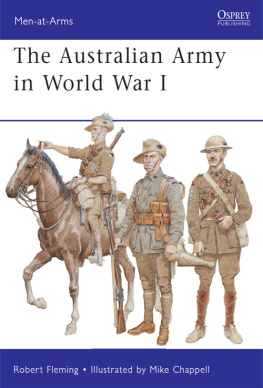

The military machinery was soon under way. The Australian navys ships began coaling, and inside the Defence Department heads were bent over plans to raise, equip, and despatch an army of volunteers to be called the Australian Imperial Force, under the command of Major General William Bridges, to stand beside Britain on the battlefields of Europe. Meanwhile, a small separate force, called the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (AN&MEF) was sent off to seize the German New Guinea colonies.

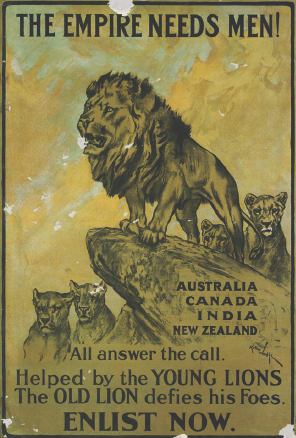

Arthur Wardle, The empire needs men (1915, lithograph on paper, 74.8 x 50.4 cm, AWM ARTV00819)

The British lion calls on her dominions and colonies to provide troops for the war.

The 20,000-strong AIF contingent began leaving its home ports in September to assemble in St Georges Sound at Albany, Western Australia. Twenty-six troopships were joined by ten from New Zealand, while two more took on local troops in Fremantle. On 1 November they were all under way, a convoy of eager men destined for the fighting front. But instead of going to Europe, as they had expected, these troops were diverted to defend Egypt and the Suez Canal, because Turkey had just joined the war on Germanys side.

The first contingent was just a beginning for the AIF. It would eventually grow into a large force comprising five infantry divisions and virtually two of light horse.

THE AIF

In 1914 military service was compulsory for young males in Australia, but it was only part-time. This militia was for local defence and not available for use beyond Australia. Following the outbreak of the war, it was necessary to raise a separate army for overseas service. Regarded as a part of the empires overall effort, the new all-volunteer expeditionary force was named the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) by General Bridges. A similar thing was done in the Second World War, and that force became known as the Second AIF.