FATAL CHARGE AT GALLIPOLI

The Story of one of the Bravest, and Most Futile, Actions of

the Dardanelles Campaign

This edition published in 2015 by Frontline Books,

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS

Copyright John Hamilton, 2004

The right of John Hamilton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-84832-902-7

eISBN 9781473847644

First published as Goodbye Gobber, God Bless You

by Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Ltd., 2004

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

For more information on our books, please email: info@frontline-books.com,

write to us at the above address, or visit:

www.frontline-books.com

To all the men who lived and died

in the Gallipoli campaign of 1915.

Lest we forget.

Contents

8th Light Horse

By Cuthbert Flynn

Lengthening shadows on lonely graves, blistering bones in the sun,

And I work here at a dreary desk, with a pen instead of a gun.

And yet I belonged to the 8th Light Horse, of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade,

You remember us clattering through the streets, the workmanlike show we made;

And dont you remember the waving flags, and the crowd, and the storm of cheers,

The women that laughed, and prayed, and wept the maidens who smiled through tears;

And I rode then, with Peter and Ben, their knees pressed hard to mine,

Pete never came back from bloody Anzac, Ben died at Lonesome Pine.

And the shadows lengthen on Peters grave; Bens bones bleach in the sun,

And I sit here, with a pen in my ear, while they fall one by one.

I wonder how many are left of the men, of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade,

How many have fallen of those brave chaps, who fought as hard as they played,

Its not so long since we laughed at the men who plugged along per boot,

But the 8th Light Horse wouldnt stay behind when the guns began to shoot.

With scarcely a thought for the horses they brought, they went on board with a cheer,

They blazed their track at grim Anzac and I sit lonely here.

Out of six hundred and fifty men, answered the roll-call a score,

The horses may wait on the lines awhile, their riders will come no more.

Tiny and Lofty, Peter and Mick, all of us comrades true,

We lived and loved, and worked and played, and quarrelled as comrades do.

And I remember how Lofty laughed, and the way Mick brushed his hair;

They all of them fell in that one mad rush bar me, and I wasnt there.

Ill bet they were first in that frenzied burst when the 8th Light Horse went down

In a hail of shell, and a blast from hell, that won them a heros crown.

Lofty lies broken on Turkish soil, Micks eyes stare at the sun;

And Tiny has gone to his last account, with his fingers clutching his gun.

The skies are blue, and the air is clear, and the sun shines overhead,

But I could choke when I think of the smokes Ive borrowed from men who are dead.

The dearest mates that a man could have, are numbered among the slain.

The men that turned out to stables with me will never do stables again.

No more will reveille awake Jim McNally he too is gone with them all;

Tis easy to die, do you wonder that I was silent at dutys call?

But the shadows still lengthen on lonely graves, the bones still bleach in the sun,

And I sit here at a dreary desk, with a pen instead of a gun.

So shed me a tear for the gallant 8th, of the 3rd Light Horse Brigade,

Who went to their death with as steady a nerve as they rode out on parade,

And if they discarded a few odd clothes if they didnt look pretty well,

They sewed a patch on the back of their shirts, and they charged like the hammers of hell.

They didnt hang back, on the slopes of Anzac through a solid wall of lead;

They dashed and then they died like men God rest their gallant dead.

And I wonder whatever they think of me, in their shallow graves in the sand,

That I didnt charge with them at grim Anzac,

That the tears of a woman held me back,

And the clutch of a babys hand.

Introduction:

The Hill of Valour

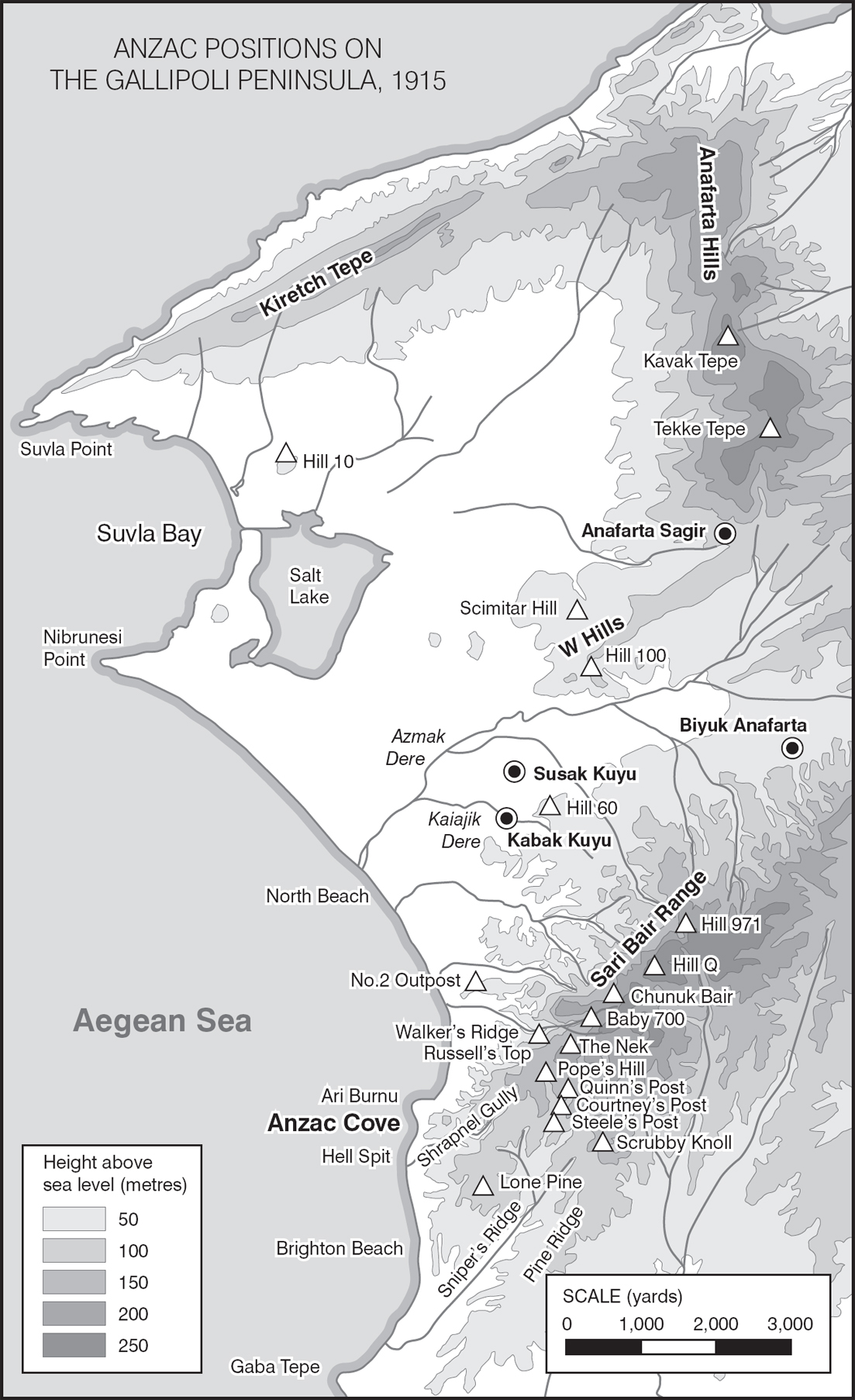

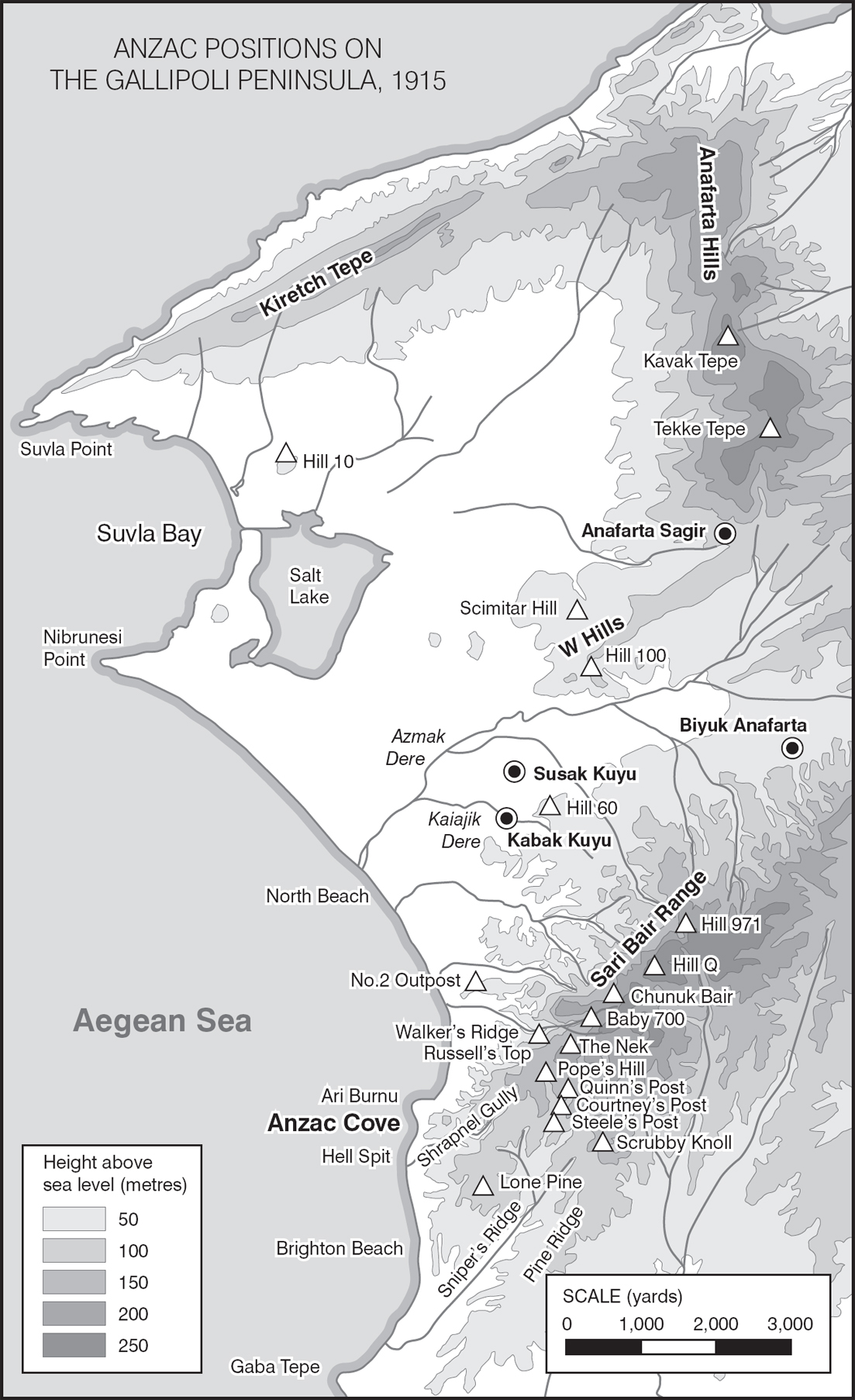

H igh above Anzac Cove on the Gallipoli peninsula is a place where few visitors stop because there is so little to see: a tiny war cemetery called The Nek at Russells Top, up Walkers Ridge.

Most Australians and New Zealanders knew of the bloodstained Walkers Ridge once. It was as famous and familiar in battlefield despatches as the Dardanelles campaign itself.

Today you dont have to climb the ridge to get to The Nek. You can drive there, taking a small turn-off from the road that now snakes its way along the front lines between the battlefields halfway up the Sari Bair Range.

You can walk much of this road in less than an hour. Famous names like Lone Pine and Quinns Post are marked, other stop-off points, and you stride on from them, up the hill past The Nek, to the bushy bumps known as Baby 700 and Battleship Hill, and then on further up to the commanding hump of Chunuk Bair. Everything is so close here. Chunuk Bair is only a few kilometres from where the first Australians landed at the Cove on 25 April 1915, way down there below the wrinkled crevices and to the left.

The Anzacs front line here was reached from North Beach below by the long and dangerous climb up this rough and jagged spur. Men toiled up and down here constantly with food, ammunition and water. Or they waited it out, simply existing in shallow burrows and on ledges on the sides of Walkers Ridge. They were under constant threat by snipers hidden in the crags around them and by sudden, vicious bursts of exploding shrapnel, as they waited their turn to go up, yet again, and fill the trenches facing the Turks only a matter of metres away at the top.

At the end of that first day, 25 April, there were 2,000 men dead or wounded, and on the beach the gravel and the rocks were slippery with their blood.

By the end of eight-and-a-half months of the Gallipoli campaign, nearly 60,000 men would have lived on the heights, the slopes and the valleys here, like rodents, scuttling along the maze of trenches and saps, with the flies forming a constant blue-green spread on their food to match the colour of the swollen corpses in No Mans Land. A trench life of bullets and bombs, snipers and shrapnel, blood and bayonets, diarrhoea and enteric fever.

![Lt Col C. G. Powles - THE NEW ZEALANDERS IN SINAI AND PALESTINE [Illustrated Edition]](/uploads/posts/book/399129/thumbs/lt-col-c-g-powles-the-new-zealanders-in-sinai.jpg)