GALLIPOLI VICTORIA CROSS HERO

The Price of Valour: The Triumph and Tragedy of Hugo Throssell VC

This edition published in 2015 by Frontline Books,

an imprint of Pen & Sword Books Ltd,

47 Church Street, Barnsley, South Yorkshire, S70 2AS

Copyright John Hamilton, 2012

The right of John Hamilton to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

ISBN: 978-1-84832-903-4

eISBN 9781473847576

First published as The Price of Valour: The Triumph and Tragedy of a Gallipoli Hero,

Hugo Throssell, VC

by Pan Macmillan Australia Pty Ltd., 2012

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in or introduced into a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means (electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording or otherwise) without the prior written permission of the publisher. Any person who does any unauthorized act in relation to this publication may be liable to criminal prosecution and civil claims for damages.

CIP data records for this title are available from the British Library

For more information on our books, please email: info@frontline-books.com,

write to us at the above address, or visit:

www.frontline-books.com

To Hugo Vivian Hope Throssell

To you, all these wild weeds

And wind flowers of my life,

I bring, my lord,

And lay them at your feet;

They are not frankincense

Or myrrh,

But you were Krishna, Christ and Dionysos

In your beauty, tenderness and strength.

Katharine Susannah Prichard

Contents

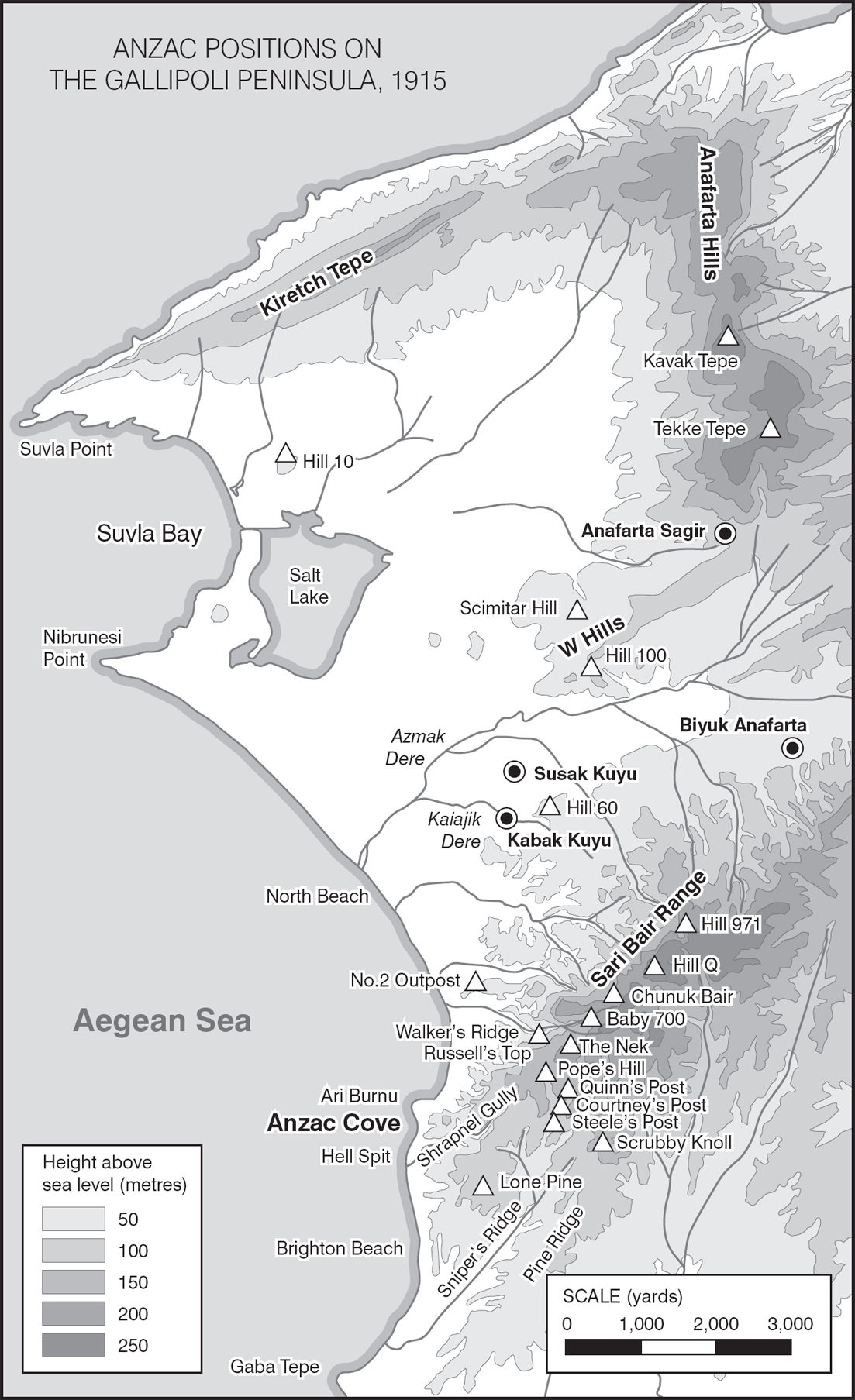

Introduction:

Bomba Tepe

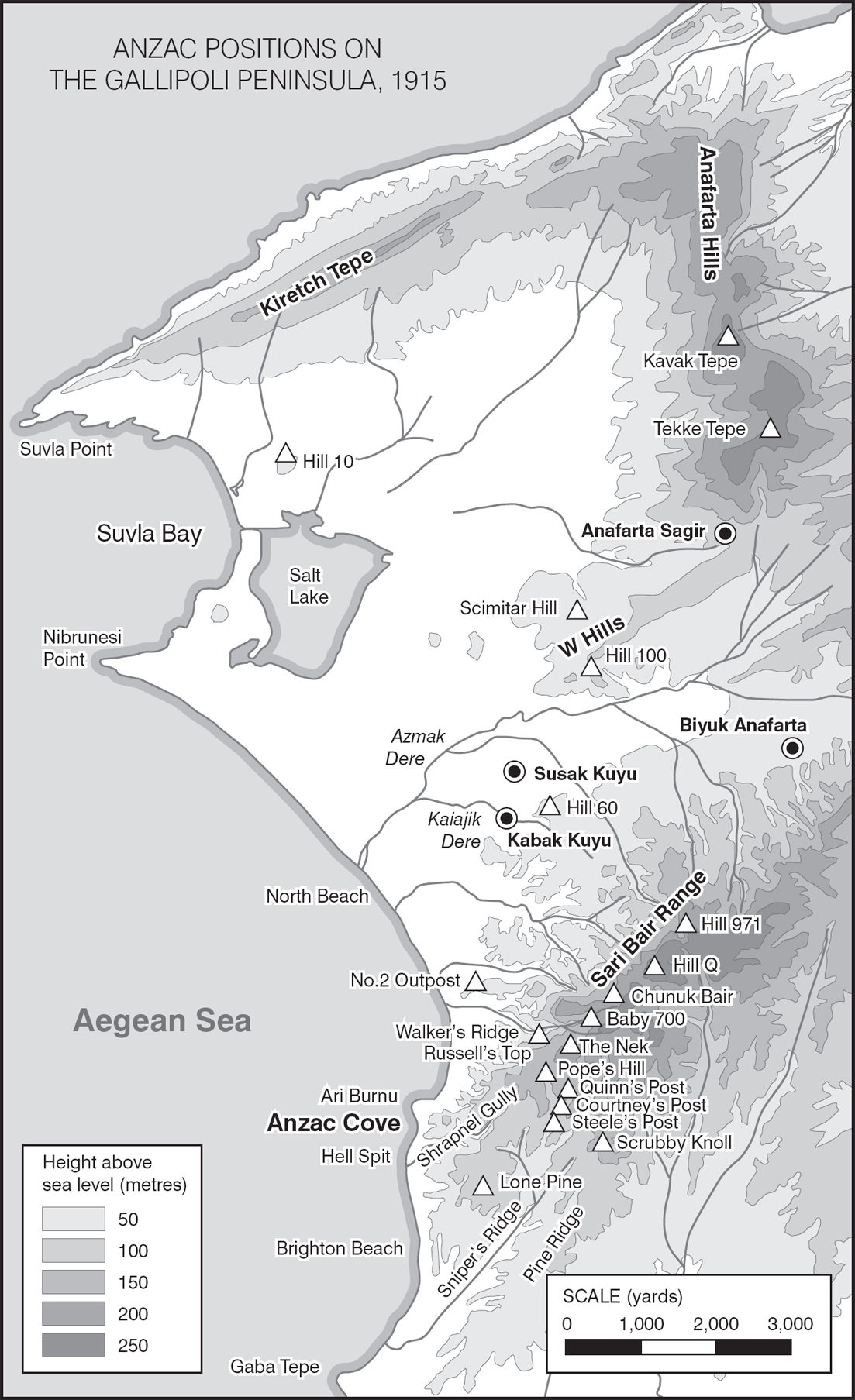

I n the records of the First World War, the Suvla campaign on Gallipoli has come to mean failure, the well-tended war cemeteries, with their row upon row of flat markers, reminders of Allied disasters. Not many visitors come to this great plain now, with its gentle foothills climbing through thick, thorny, bush-covered spurs to the commanding heights of Sari Bair. Not many come to its war cemeteries, either. The flowers are tended and the grass is mown between the rows of headstones by Turkish workers employed by the Commonwealth War Graves Commission, but there are no worn footpaths here as there are at Anzac, marking the annual passage of thousands of Australian and New Zealand pilgrims. Few of these visitors bother to travel northwards on and up to Hill 60.

In winter Suvla is a forbidding place, bleak, windswept and very cold. In summer the great salt lake by the sea shimmers white in the heat, the fields are parched and brown with stubble, the scrub is thorny and impassable, and there is heat, more heat, and plagues of flies. That is when Hugo Throssell and the foreigners fought here, when the days were hot and the nights were often bitterly cold.

Yet springtime in Suvla is a warm, welcoming season when the plain and the foothills are green and beautiful, larks sing, the air hums with bees droning about their business, and wild crimson and dark, black-centred poppies sprinkle the landscape like drops of blood. It is springtime on Gallipoli when I visit; there has been a long, cold winter followed by heavy rains. The weather is still very changeable as the sap oozes white from fresh green shoots in the sunshine and the earth stirs for another season. It is cool and drizzly one day, warm and soft the next. Boot-clogging mud that drags your feet down dries out quickly and puffs up like dust as you walk along the same track twenty-four hours later.

The fields have been ploughed into thick brown furrows. Wheat is already vivid green, and other crops are being planted. When the battle for the hill and has its own memorial, a big cross in the centre of the cemetery recording the names of 182 officers and men who have no known graves. The main flat memorial stone in front of the cross provides a convenient table for compass and maps, to help you to get your bearings as you near the summit of Hill 60.

Kenan leads the way out of the cemetery and heads onwards up the slight hill. Suddenly, the evidence of war is everywhere. Lead shrapnel balls sit in furrows like round grey slugs, squares of rusty iron bomb fragments lie as neat as chocolate blocks, twisted scraps of spent green copper bullet casings pepper the soil, and short lengths of barbed wire sprout from the ridges. Then we see traces of a lost generation. A shirt button. The eyelet from a soldiers boot, still with a shred of leather attached. And then the human remains. Bone shards at first, some looking like pieces of white honeycomb, but brittle, and crumbly like aged cheese, others smooth, like creamy marble. And, in a deep furrow, unmistakably part of a femur.

The wind sighs again as Kenan leads me into a thick patch of pine forest. We push our way between branches that whip at our faces, our footsteps deadened by the thick brown carpet of pine needles. Kenan points. The forest floor is a maze of deep indentations: the trenches.

I try to imagine here, on this spot, Second Lieutenant Hugo Throssell in the immediate aftermath of the battle early on an August morning in 1915. Still in the trench he had charged, captured and held against the enemy in the darkness, now in the dawn, dazed, wounded and bloody, refusing to leave. A fellow officer, Captain Horace Robertson, described him:

I gave him a cigarette and ordered him to the dressing station. He took the cigarette, but could do nothing with it. The wounds in his shoulders and arms had stiffened and his hands could not reach his mouth. He wore no jacket, but had badges on the shoulder straps of his shirt. The shirt was full of holes from pieces of bomb, and one of the Australias was twisted and broken, and had been driven into his shoulder. I put the cigarette in his mouth and lighted it for him.

In August 1915, Hill 60 had become of increasing strategic importance for both sides. For the Allies, capturing the hill would mean that they held an unbroken line between Anzac and Suvla. From the hills summit the generals could keep an eye on what the Turks were up to around the two Anafarta villages. There were also two wells close to the hill, of vital importance during that hot, dry summer.

Today one of them is down the hill from an olive grove. The locals weather settles more, black irrigation piping will be put into some fields, and the village women will be out, in their head coverings and baggy pants, stooping low as they plant tomato seedlings. In the little villages where they come from, like Biyuk Anafarta and Anafarta Sagir, the men will wait to take them home, sitting outside the town cafe in the shadow of the minaret, stirring lumps of sugar into their glasses of strong tea or cups of thick, sludgy coffee, talking as they always have of weather and crops, religion and politics.

There may be the distant thunder of Turkish Air Force jet fighters on patrol overhead. The Dardanelles remains strategically important. Like the bees guarding their hives on the Suvla plain, the Turks are suspicious and alert, welcoming visitors but still wary. The red Turkish flag with its white crescent moon and star flaps proudly from many flagpoles. In every cafe, every business, every home, there is a plaque or portrait of Mustafa Kemal Atatrk, the first president and founder of modern secular Turkey, the wartime colonel with eyes like a hawk who once gazed down on Hill 60 and directed the battles against the invaders, the infidels, from the heights above.