BACKGROUND AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Gallipoli and I go back a long way.

As the youngest of seven kids, born to parents who had returned from serving in the Second World War to carve out a farm in the bush at Peats Ridge just an hour north of Sydney the very name Gallipoli resonated for me like no other. A place of extraordinary deeds, of inspiring courage and sacrifice, it made you proud to be an Australian. Knowledge of it went with being an Australian. I learned about it at primary school; I heard about it every Anzac Day service up at Central Mangrove RSL; and I frequently thought about it, at the going down of the sun, and in the morning

Sure, I was sort of proud of Mum and Dad and their service in the Second World War Mum as an army physiotherapist, helping rehabilitate the veterans of Milne Bay and Kokoda; and Dad at El Alamein and in New Guinea but it wasnt as if they had been at Gallipoli, where I knew the real action had taken place.

I studied it quite seriously at high school, I read about it on my holidays and wrote an essay on it while at the University of Sydney. My reverence for it blossomed to the point that, as a rugby player living and playing in Italy in the mid-1980s, on my 84/85 Christmas break, I drove my tiny little Fiat all the way through the Iron Curtain, through Yugoslavia and Bulgaria to first Istanbul, and then of course down to Gallipoli.

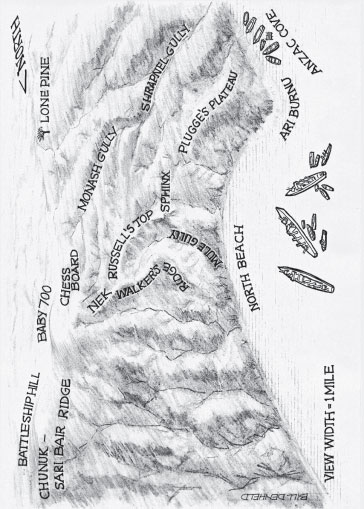

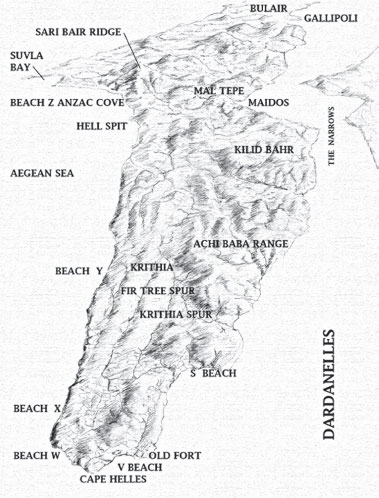

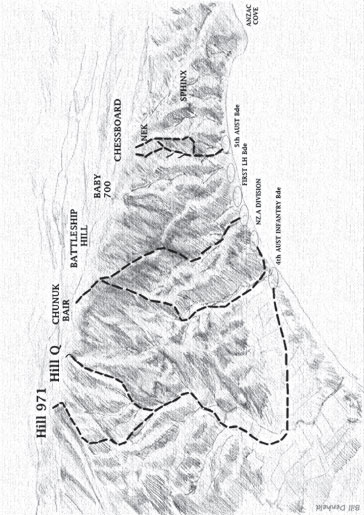

Alone long before visiting these battlefields had become something of a rite of passage for many young Australians I wandered around, awe-struck at the savagery of the terrain, how the cliffs rose all but straight from the shore, how the trace of the trenches meandered in parallel lines so close together, how some of the gullies theyd fought in and for looked rather more like abysses to my eyes.

Standing on the beach below the spot known as The Sphinx, I noticed a great deal of erosion in the landscape all around, and wondered about it until I suddenly realised. That was not mere erosion, it was the scars of thousands of artillery shells hitting those hills!

At Lone Pine Cemetery, amid all the gravestones marked with such words as DUTY NOBLY DONE, HE DIED IN A FAR COUNTRY/FIGHTING FOR/HIS NATIVE LAND, A MOTHERS THOUGHTS OFTEN WANDER TO THIS SAD AND LONELY GRAVE I noted an epitaph that quite shocked me, going something like DIED IN A FOREIGN FIELD. AND FOR WHAT?

Coming back from the battlefield towards the nearest town Gallipoli itself I gave three hitchhiking Turkish workers in blue overalls a lift up to the next town, and though the language barrier between us was insurmountable, I was a tad amazed that they seemed extremely friendly, even after I identified myself as steady, fellas, steady an Australian.

Would I be so hail-fellow-well-met with someone from a nation that had come to my shores and killed 90,000 of my countrymen?

No.

I returned home to Australia, proud that I had made my pilgrimage to sacred soil, and then embarked on a journalistic career, covering many subjects but always with an eye out for Anzac Day stories. I was particularly stunned by the reaction I received to a yarn I wrote about a cricket match played on the shores of Gallipoli, even while Turkish shells were bursting all around. Letters, phone calls, people stopping me in the street, expressing their wonder at the Diggers bravery

Many years on, stories of Gallipoli were still striking so many chords with the Australian people you could play an anthem to it. In the late 1990s, for no reason I can think of, I suddenly started taking my kids to Anzac Day services in town.

In April 1999, I was in my car heading down Sydneys Market Street, about to turn left onto Sussex Street, to the Sydney Morning Herald building, when some highbrow historian on ABC Radio used the phrase when the Australians invaded Turkey, at Gallipoli.

Invaded? Such an ugly, aggressive, non-reverential word! Yes, I suppose, technically, Gallipoli was on Turkish soil even though it was GALLIPOLI and, strictly speaking, if you wanted to really get pernickety about it, our blokes didnt really have the Turkish blessing to land on their shores. So, if your measure was hoity-toity historical, then it just possibly could be construed as an invasion, so long as you put some monster quotation marks around it. But it sat very uncomfortably with me, and was the first time I had been obliged to think of the whole idea of the landing on Gallipoli shores in less than holy terms. But the more I thought about it as the years passed, the more I drifted into a rather more sober view.