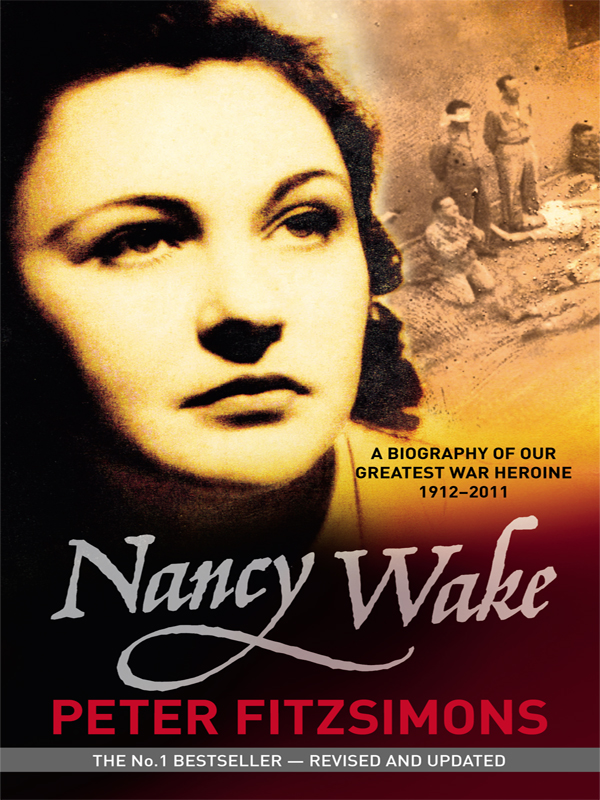

To my late parents, who proudly served Australia in the Second World War, as Lieutenant Peter McCloy FitzSimons, 2nd/4th Light Anti Aircraft of the Ninth Division, AIF (North Africa [El Alamein], New Guinea [Finchaven and Dumpu]) and Lieutenant Beatrice Helen Booth OAM (AIF Physiotherapist in Darwin and Bougainville). And to all the brave men and women who served with them. We dips our lids.

One hour of life, crowded to the full with glorious action, and filled with noble risks, is worth whole years of those mean observances of paltry decorum.

W ALTER S COTT

D uring the mid1980s, while living and playing rugby in la France profonde at the tiny village of Donzenac, in la Corrze I often used to have a drink at Madame Salesses caf with my aged friend Martin, the local garage proprietor. A fairly meek and mild bloke he might have been when I knew him, but not during World War II. Then, his nom de guerre had been Tin-Tin and, as one of the most ferocious fighters of the local Resistance movement, he had been the scourge of the Germans.

Et lAustralienne, Nonc-eeeee Wake, Peterrrr, he asked me once, early in our friendship. Tu la connais?

No, I didnt know Nancy Wake, or at least I had never met her. But Martin knew a lot about her. She was a legend, he said, one of the hardest fighters the partisans had ever had, a leader, a great organiser, fearless, fantastic. And also trs belle , he mentioned with a twinkle, even all those years on. He had not fought with her side-by-side, he said, as she was with the partisans in the neighbouring region of Auvergne, but her fame knew no borders, and he had been very proud to meet her once at a safe house in Aurillac, about one hundred kilometres away.

From time to time over the next four years, I would hear her name from the old ones this amazing Australian woman who, to the locals, went by her own nom de guerre of Madame Andre. She had been in this region four decades before me and had covered herself in so much glory, that I would always walk a little taller that my countrywoman had acquitted herself so well and was remembered so fondly. Yet, even when working back in Australia as a journalist for the Sydney Morning Herald, I never came across her, though I do remember hearing somewhere that she was living quietly up in Port Macquarie on the New South Wales north coast. One day, I thought, Id really like to meet her if the opportunity ever presented itself

More than a decade passed. Then, a phone call to me at the Herald out of the blue from my old rugby coach, Peter Fenton the coach, incidentally, of the Sydney team with whom I first landed in France in 1984. Did I remember Bob Cowley, he wanted to know, who once scored a famous intercept try against Northern Suburbs for Parramatta?

No.

Oh, well anyway, Bob had a brother called Jim who lived in Port Macquarie and he was a very close friend and keen supporter of Nancy Wake, the most decorated heroine of the Second World War. Jim wanted to know if I would give him a call, because he wanted to talk to me about Nancy, and about a possible story for my newspaper. On my way, chief!

I indeed met the woman in question in her Port Macquarie apartment, and conducted the interview for a Herald story for Anzac Day. But that was not all so impressed had I been when I met her, so riveted by even the barest rudiments of her life story, that even as I was about to embark from Port Macquarie airport that afternoon for the last flight to Sydney I called my commissioning editor at HarperCollins, Alison Urquhart, and said: Im going to write a book on Nancy, and youre going to publish it.

I did, they did, and here it is At its conclusion, my chief hope is that I have done her story justice.

A Cry in the Night

The good stars met in your horoscope,

Made you of spirit and fire and dew.

R OBERT B ROWNING

Quoted on the title page of Nancy Wakes favourite book,

Anne of Green Gables , by Lucy Maud Montgomery.

I n a dingy little room at the back of a modest weatherboard home in the suburb of Roseneath, the air was thick with exhaustion, the sheets and floor nearby lightly spattered with blood and wetness. On the bed, a woman was just starting to recover from the searing waves of pain that had been washing over her during the supreme effort of giving birth. Even though this was her sixth child yet her first for eight years it never seemed to get any easier, only ever made her progressively more tired. In the gusty heights of windy Wellington, on the thirtieth day of August 1912, the timeless scene of human birth had just taken place and Ella Wake lay back exhausted, totally spent. A woman hovered close a tapuhi, the Maori word for midwife and she was positively beaming with happiness. Cradling the babys head in the crook of her bountiful arms, she pointed to the thin veil of skin which covered the top part of the infants head, known in English as a caul.

This, she said softly tracing a gentle finger across the fold of extra membrane, is what we call a kahu and it means your baby will always be lucky. Wherever she goes, whatever she does, the gods will look after her.

The mother groaned and lay back in the bed.

If so, so be it. At that particular time Ella was simply too tired to care and had room only for relief that her exhausting effort was over though she would at least tell her daughter the story of the Maori midwifes predictions many times for years afterwards.

Ella Rosieur Wake came from an interesting ethnic mix, her genetic pool bubbling with material from the Huguenots, the French Protestants who had famously fled France so they could pursue their religion freely, and Maori, as her English great-grandmother had been a Maori maiden by the name of Pourewa. She had been the first of her race to marry a white man, in the person of Nancys English great-grandfather Charles Cossell, and they were wed by the Reverend William Williams at Waimate Mission Station on 26 October, 1836. Legend has it that the great Maori chieftain, Hone Hoke, had loved Pourewa himself, and had sworn death to them both, but had been killed in the Maori Wars before fulfilling his threat.

In sum, Ellas people went a long, long way back in New Zealand, and physically she was like the land itself, rustically beautiful. As to personality though, the least that can be said is that she seemed to have inherited very little of the famous French joie de vivre or perhaps it had simply been drained out of her over the long, hard years of child-raising. Rather, she always seemed to project a kind of long-suffering religious rectitude, a dowdy air that life was duty and duty was hard; hard was her lot and lots of children made it harder still.

Young Nancys father, Charles, however, was of solid English stock and was an entirely different sort of person. An extremely good-looking, tall man of easy, extroverted charisma and enormous warmth, he was a journalist/editor by trade, then working on a Wellington newspaper. He was a dapper dresser who never seemed to have a worry in the world, and there must have been some wonder from others how such a different pair as he and Ella could have managed to marry and make it, but their large brood seemed testament to the commitment they had to each other.

True, Nancy cannot remember her parents ever showing affection for each other, but that may well have been because she could simply never see past the affection her father showed her . In her young life, she loved nothing better than sitting on her fathers lap in his big easy chair, with him either reading stories to her, or dancing around the room to the sound of an ancient gramophone, or just cuddling and chatting gaily. In her memory at least, the two would laugh and joke and carry on for hours on end, and just as she instinctively felt that she was her fathers favourite, she also had a vague sense that her other brothers and sisters, not to mention her own mother, resented her for it. Not to worry, life was too good to care.