About the Book

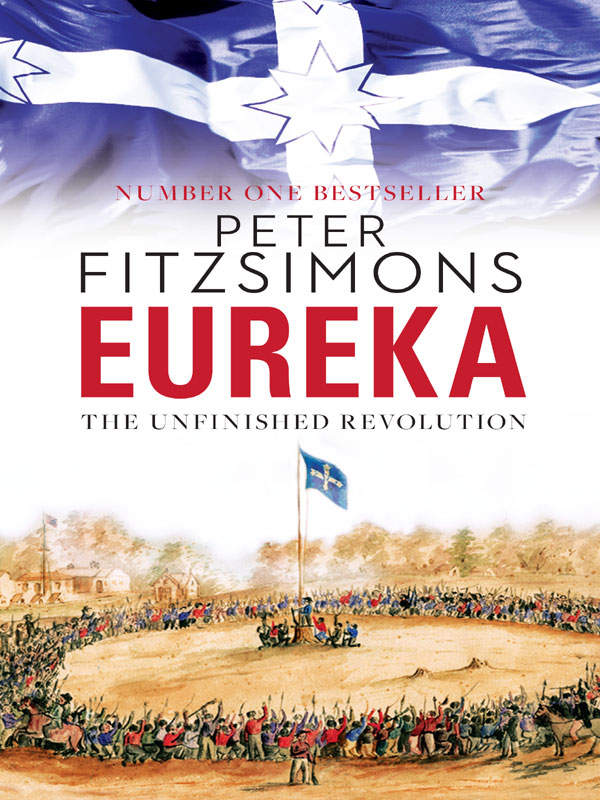

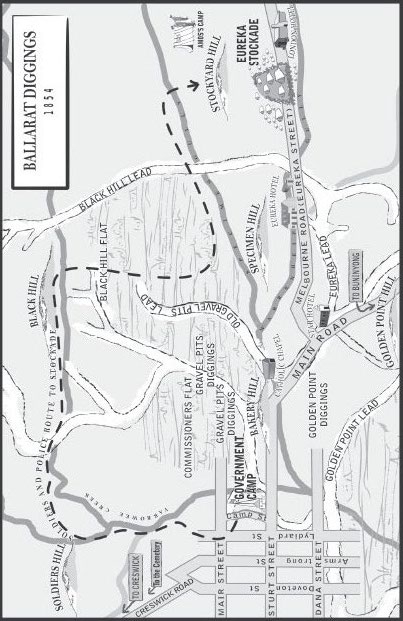

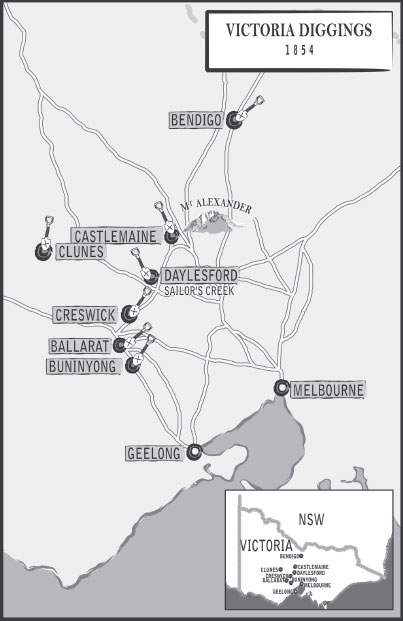

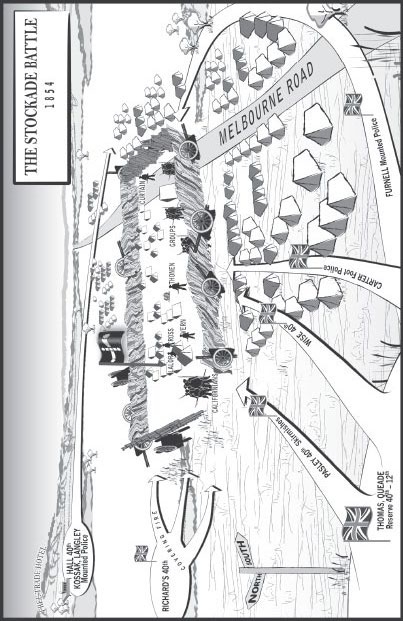

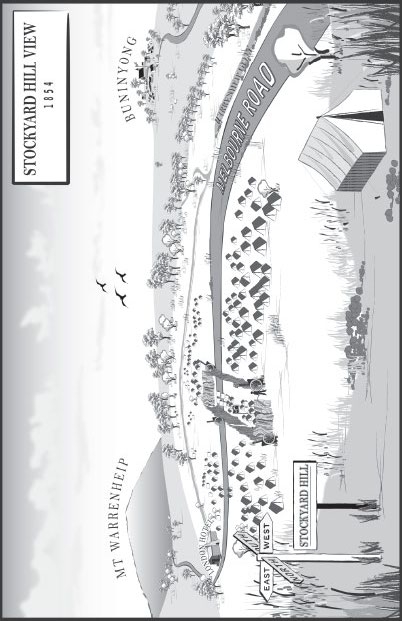

In 1854, Victorian miners fought a deadly battle under the flag of the Southern Cross at the Eureka Stockade. Though brief and doomed to fail, the battle is legend in both our history and in the Australian mind. Henry Lawson wrote poems about it, its symbolic flag is still raised, and even the 19th-century visitor Mark Twain called it a strike for liberty, a struggle for principle, a stand against injustice and oppression.

Was this rebellion a fledgling nations first attempt to assert its independence under colonial rule? Or was it merely rabble-rousing by unruly miners determined not to pay their taxes?

In his inimitable style, Peter FitzSimons gets into the hearts and minds of those on the battlefield, and those behind the scenes, bringing to life Australian legends on both sides of the rebellion.

Contents

To Raffaello Carboni, Mrs Ellen Clacy, William Craig, Samuel Huyghue, Samuel Lazarus and William Bramwell Withers, whose contemporary and, in the case of Withers, near-contemporary accounts I have most enjoyed and relied upon in the formation of this book. And to all those diggers who fought so valiantly

By and by there was a result, and I think it may be called the finest thing in Australasian history. It was a revolution small in size; but great politically; it was a strike for liberty, a struggle for principle, a stand against injustice and oppression It is another instance of a victory won by a lost battle. It adds an honourable page to history; the people know it and are proud of it. They keep green the memory of the men who fell at the Eureka Stockade, and Peter has his monument.

Mark Twain after visiting the Victorian goldfields in 1895

Eureka was more than an incident or passing phase. It was greater in significance than the short-lived revolt against tyrannical authority would suggest. The permanency of Eureka in its impact on our development was that it was the first real affirmation of our determination to be masters of our own political destiny.

Ben Chifley, Labor Prime Minister

The revolt at Eureka is the one picturesque bloodstain on the white pages of Australian history. British officials referred to it as a trifling affair but the little fight was big with results, for it helped to shatter official tyranny and to establish democratic rule in Australia.

The Lone Hand , January 1912

BACKGROUND AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Like most Australians, the saga of the Eureka Stockade is in the very marrow of my bones. As a primary school kid in the late 1960s, I recall both the fun of participating in a mock Eureka Stockade re-enactment at the Mangrove Mountain Community Fair, and being pleased that I got to dress up as a good rebel and not in the red coat of a bad British soldier. We learnt about the subject briefly at Peats Ridge Public, and it was almost as much fun a legend from Australias past as the bushrangers not that I was particularly interested in the Eureka saga academically.

Nevertheless, in Mr Rex Wards history class at high school in Sydney in the mid-70s, that changed. On one particular sleepy afternoon I was doing what I usually did in history class multiplying the number of bricks on the wall from top to bottom, by the number of bricks from left to right when Mr Ward started his lesson on the Eureka Stockade. Remembering Mangrove Mountain and the excitement of it all, my ears pricked up and, for the first time in months, I not only sat up straight but went further. Out of pure bloody-mindedness I began to listen , and it was right there and then that my love of Australian history began my enthrallment with that particular story sparked a wider, burning passion. The action! The characters! The fact and this was perhaps the key that this was a real Australian story!

The leap forward to this book, however, was only relatively recent. A couple years ago, at a meeting of the directors of Ausflag in the Sydney suburb of Crows Nest, we were sifting through many worthy submissions from our fellow citizens of what a modern Australian flag should look like when the thought struck me: what a pity we Australians dont have our own version of the Americans legendary Betsy Ross story, that countrys purported maker of the first Stars and Stripes flag during the Revolutionary War.

While the designs we were seeing were mostly admirable, I had my doubts as to whether the Australian people as a whole would ever choose a flag designed last Tuesday ahead of one designed at the beginning of the last century, one that had been fluttering ever since.

And that, of course, led me to thinking about the Eureka story as the possible subject for a book. Look, I certainly didnt think that the flag of the Southern Cross would ever be embraced as the answer in the 21st century it is too associated with either right-wing racist rednecks who brandish it as a symbol of white Australia or hard left-wing members of the union movement who, far more admirably, wave it for workers rights. But, against that, Eureka was certainly a saga that encompassed our oldest and best-known flag after the national flag, and so it might be worth exploring anyway. All this happened in roughly the same time frame that my friend and researcher Henry Barrkman started suggesting that Eureka would be a good subject for me, and a producer from SBS Radio in Melbourne, Yvonne Davis, wrote to me, pointing out that the multicultural aspects of the saga had never been truly explored. (Multicultural aspects? What multicultural aspects? I wasnt really aware that there were any?) And then, the breakthrough Out of the blue, two brothers, Peter and Ron Craig, wrote to me saying they were the great-grandsons of William Craig, who had not only come out on the ship from Ireland with the hero of the piece, Peter Lalor, but also penned a long-forgotten book about Lalor and his experience in the Eureka Stockade. Given that I was interested in writing books on Australian history, they wondered if I would like to read their great-grandfathers original manuscript?

I would, and I did. We wined, we dined, we talked. I was hooked, and soon afterwards I began.

Rarely have I been so enthused while working on a book. Yes, I have been equally passionate about other stories, just as stories, but with this one I felt I was getting to uncover the very foundation stones of what it is to be an Australian from multiculturalism to mateship, from our broad distrust of the elites who would seek to rule over us, to our wide embrace of egalitarianism and insistence on a fair go, mate, to the very use of the word mate! In the diggers willingness to roll up their sleeves and just get on with it, whatever the appalling conditions, and their propensity to pull together to overcome hardships, I recognised much of the spirit that the country was built on. In their refusal to cower before power most particularly their loud insistence to the government of no taxation without representation and backing that up with their willingness to fight for their rights, even against overwhelming odds, I found fascinating parallels with the Boston Tea Party that I had never before appreciated.