About the Book

Down came our barrage onto the enemy lines and Pozires village, the Germans replying with artillery and machine-gun fire. As we lay out in No-Mans Land we could see the bullets cutting off the poppies almost against our heads

Lance-Corporal Harold Squatter Preston of the 9th Battalion

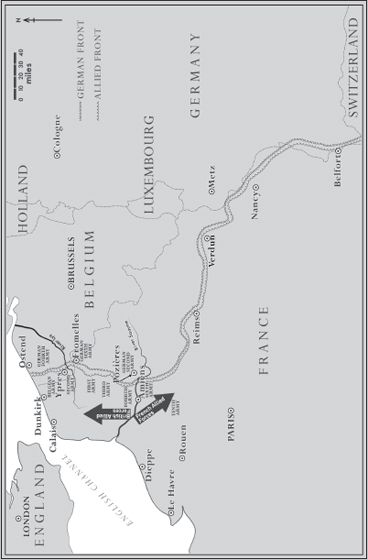

On 19 July 1916, 7000 Australian soldiers in the first major action of the AIF on the Western Front attacked entrenched German positions at Fromelles in northern France. By the next day, there were over 5500 casualties, including nearly 2000 dead a bloodbath that the Australian War Memorial describes as the worst 24 hours in Australias entire history.

Just days later, three Australian Divisions attacked German positions at nearby Pozires, and over the next six weeks they suffered another 23,000 casualties. Of that bitter battle, the great Australian war correspondent Charles Bean would write, The field of Pozires is more consecrated by Australian fighting and more hallowed by Australian blood than any field which has ever existed

Yet the sad truth is that, nearly a century on from those battles, Australians know only a fraction of what occurred. This book brings the battles back to life and puts the reader in the moment, illustrating both the heroism displayed and the insanity of the British plan. With his extraordinary vigour and commitment to research, Peter FitzSimons shows why this is a story about which all Australians can be proud. And angry.

BACKGROUND AND ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

Fromelles? Pozires? Something to do with the Western Front in the First World War, werent they?

I mean, as a little boy, my Second World War veteran father taught me the most famed First World War poem In Flanders fields, the poppies blow,/ Between the crosses, row on row,/ That mark our place; and in the sky/ The larks, still bravely singing, fly/ Scarce heard amid the guns below and I gathered Fromelles was in French Flanders, yes?

And, yes, later on at high school, there might have been passing reference to both battles in Rex Wards Modern History class, but after that faded, there was little left in my memory, let alone my heart, other than a vague presentiment that they had been important conflicts. While Gallipoli came up again and again in conversation, on the TV, in the papers, in books Fromelles and Pozires were no more than names that occasionally I would see referred to in passing, in the same breath as Bullecourt, Passchendaele, Polygon Wood, Villers-Bretonneux and the like you know, key battles in the fight for the whole Western Front?

No?

Well, me neither. As a younger man, I could never quite get my head around what the whole thing had been about, beyond the fact that our own weird mob were with the Allies on one side, and the Germans were on the other side. And I gathered the slaughter had been unimaginable.

Interest slowly grew, however.

For the 80th anniversary of Armistice in 1998, I interviewed for The Sydney Morning Herald Paul Fischer, a 101-year-old former French soldier on the Western Front whod become a Professor at the Sorbonne, before moving to Australia with his wife in the early 1960s to be close to their only daughter. He lived just 50 metres down the hill from my home on Sydneys Lower North Shore, and his story quite stunned me.

I remember many things, he told me. The bombardments, the screaming, the death, ctait terrible, mais vraiment terrible! Le capitaine would lift his arm to signal to make ourselves ready to attack, and when he dropped it, we had to scramble up and out and follow our bayonets towards les Allemandes .

Back then, he said, he looked on every sunrise as if it would be his last, and for the vast majority of his comrades, it was. And yet here he was, eight decades later, still going strong ish apart from the nightmares still powerful enough to wake him in the night, with only his wife of 63 years, Lynette, able to hold him, to calm him, to assure him, cherie , that it was over, that he was not back there once more.

This, clearly, was a man who had known things, seen things, experienced things, of which I had not the slightest conception.

A couple of years later, while writing the biography of Wallaby captain John Eales, I was entranced by the words with which Wallaby coach Rod Macqueen had inspired his charges before the 1999 World Cup Final. In the dressing room with just two minutes to go before going out onto the field at Cardiff, Macqueen cited the teams visit to Villers-Bretonneux the previous year, before quoting the special order of one-time Victorian clergyman Lieutenant F. P. Bethune to his men before the battle: This position will be held, and the section will remain here until relieved The enemy cannot be allowed to interfere with the programme. If the section cannot remain here alive, it will remain here dead, but in any case it will remain here. Should any man, through shell shock or other cause attempt to surrender, he will remain here dead. Should all guns be blown out, the section will use Mills grenades, and other novelties. Finally, the position, as stated, will be held.

For the second time, I felt a flicker of interest in the Western Front, and yet still that interest was nothing as to how absorbed I subsequently became in doing a biography on Nancy Wake, and books on Kokoda, Tobruk and Gallipoli. It was the book on the Anzacs at the Dardanelles, of course, that got me interested in Fromelles and Pozires. For while researching the reminiscences of many Gallipoli veterans whod gone on to those battles, a constant theme was that the Dardanelles was a picnic compared with those first two battles the Australians had engaged in in France.

I knew how bad Gallipoli was, so what must the Western Front truly have been like for them to say that? And so it began. From first reading up on those battles, I was stunned at just what occurred, and went from there with the same aim as always: to bring the whole thing back to life. The late, great American novelist E. L. Doctorow once noted, The historian will tell you what happened. The novelist will tell you what it felt like.

It is for you to judge my success or otherwise, but I strain to do both. As noted in my previous work, I want to make my account read like a novel filled with accurate, raw detail and quotations, perching on 2000 or so firm footnotes to show that it is nevertheless real. For the sake of the storytelling, I have occasionally created a direct quote from reported speech in a newspaper, diary or letter, just as I have changed pronouns and tenses to put that reported speech in the present tense and occasionally assumed generic emotions where it is obvious, even though that emotion is not necessarily recorded in the diary entries, letter, etc. I have also occasionally restored swearing words that were blanked out in the original newspaper account due to the sensitivities of the time. Always, my goal has been to determine what were the most likely words used, based on the documentary evidence presented, and what the feel of the situation was. Once again in this book, as noted in the endnotes, I have taken documented detail from one time frame and placed it in a slightly later time as the situation was almost exactly the same.