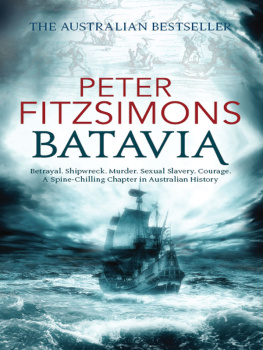

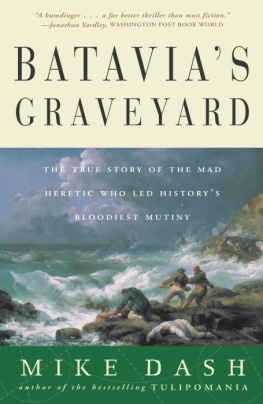

Batavia is a story of human nature at its absolute darkest I couldnt put the book down FitzSimons lays it out with admirable clarity he is excellent on those details that add necessary texture Sydney Morning Herald

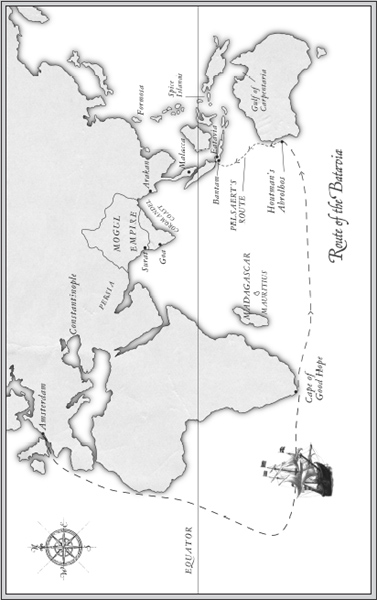

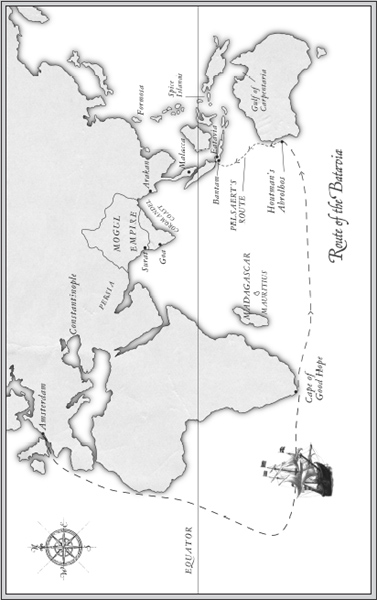

In 1629, the magnificent Batavia pride of the Dutch East India Company is on her maiden voyage from Amsterdam to the Dutch East Indies, laden down with the greatest treasure to ever leave the Dutch Republic. She is already boiling over with a mutinous plot that is just about to be put into action when, just off the coast of Western Australia, she strikes an unseen reef in the middle of the night.

While Commandeur Francisco Pelsaert decides to take the longboat across 2000 miles of open sea for help, his second in command, Jeronimus Cornelisz, takes over, quickly deciding that 220 people on a small island is too many for the scant amount of supplies they have. Quietly, he puts forward a plan to 40-odd mutineers to save themselves by killing most of the rest, sparing only a half-dozen or so women, including his personal fancy, Lucretia Jans one of the noted beauties of the Dutch Republic to service their sexual needs.

A reign of terror begins, countered only by a previously anonymous soldier, Wiebbe Hayes, who begins to gather to him those prepared to do what it takes to survive hoping against hope that the Commandeur will soon return with the rescue yacht.

Extraordinary and terrible as it seems, it all happened, long ago, and it is with very good reason that Peter FitzSimons has long maintained that this is one of the greatest stories in Australias history.

Contents

To Hugh Edwards OAM, Max Cramer OAM and

Henrietta Drake-Brockman, who did more than any in

the modern era to bring this stunning story to light.

Australian history is almost always picturesque; indeed, it is also so

curious and strange, that it is itself the chiefest novelty the country

has to offer and so it pushes the other novelties into second and

third place. It does not read like history, but like the most beautiful

lies; and all of a fresh new sort, no mouldy old stale ones. It is full

of surprises and adventures, the incongruities, and contradictions,

and incredibilities; but they are all true, they all happened.

Mark Twain, 1897

Preface

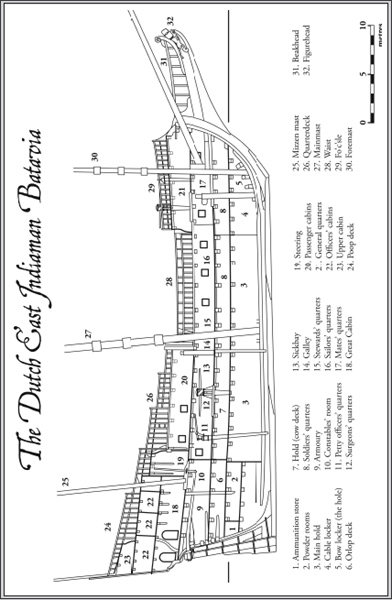

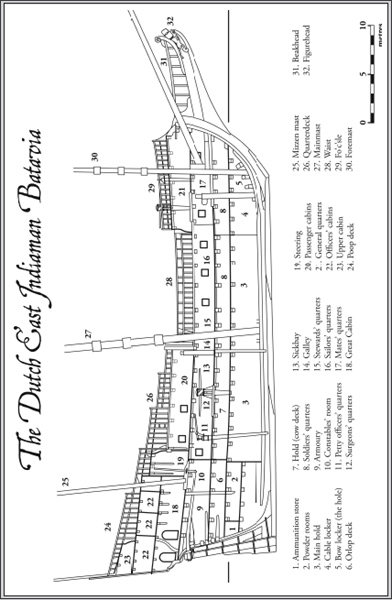

In a chance lunch conversation with my two then publishers, Shona Martyn and Alison Urquhart, late in 1999, they mentioned the seventeenth-century story of the shipwreck of the Batavia and how it might possibly lend itself to a great book. That afternoon, I went back to the library of the Sydney Morning Herald and dug up some stuff on it. I was instantly and totally absorbed. Among other things, I was stunned to read of the grandeur of the ship herself and that when her replica had sailed into Sydney Harbour a couple of months previously, to get to her berth at the Maritime Museum in Darling Harbour, she had needed to do so during an exceptionally low tide so the top of her mighty mast would fit under the Sydney Harbour Bridge. And this was a ship that was originally built nearly 400 years earlier. Staggering!

The true wonder of the story, though, had little to do with the physical dimensions of the ship and everything to do with the personal dynamics of the Batavia s company once she got into strife. Sure, a lot of the details might have been well known to many Australians, particularly in Western Australia, but they were totally unknown to me and I remember thinking at the time that the whole astonishing saga made the story of the sinking of the Titanic look like a Sunday School picnic. I frankly couldnt believe that such a fantastic story wasnt as well known in this country as Ned Kelly or the Eureka Stockade and decided then and there to write a book on it.

In short order, I had a contract to do exactly that, and I began my research. A lot of water has passed beneath the bridge since then I have been involved in many other projects, including many other books, and have changed publishing houses yet I have returned again and again for further bursts of work on the Batavia story before dedicating myself to its completion. What you hold in your hands is the result.

Over the last 400 years or so, many other authors have also been bitten by the bug of the Batavia , with the first accounts of the 1629 shipwreck appearing in the 1647 Dutch work Ongeluckige Voyagie, Vant Schip Batavia ( Unlucky Voyage of the Ship Batavia ), published by Jan Jansz. A bestseller of its time, this book was predominantly a third-person treatment of the original journal of Francisco Pelsaert, Commandeur of the fleet in which the flagship Batavia made her maiden voyage, which explains why it was frequently (and incorrectly) known as Pelsaerts Journal.

Pelsaerts actual journal describing this sorry saga from beginning to end is now kept in the Netherlands National Archives in The Hague, and it was a special thrill in the researching of this book to have held it in my hands. I am indebted to Lennart Bes of the National Archives for facilitating my access to it.

The first of the more modern Australian books on it, The Wicked and the Fair , was a fictionalised account written by Western Australias Henrietta Drake-Brockman and published in 1957. Her seminal non-fiction book Voyage to Disaster (1963) came out of her research for The Wicked and the Fair and took ten years to write. Her tireless research helped lead to the actual discovery of the Batavia by Max Cramer and his little band, working with Hugh Edwards and local fishermen, in the same year. Edwardss Islands of Angry Ghosts came out in 1966 and, among other things, describes the wonderful tale of how the two men finally came to pinpoint the site of the wreck. All of us who follow owe Henrietta Drake-Brockman, Cramer and Edwards a great debt, and I am grateful for the extent to which the two men were able to assist me in my research.

Hugh squired me around the Abrolhos Islands, where it all took place, showed me things that only a man of his deep background in the subject would know and, thereafter, was constantly steering me towards different pieces of information. As to Max Cramer, who organised the trip for Hugh and me, his eyes were the first to see the Batavia in 334 years, and he became an acknowledged world authority. Max, too, was wonderfully generous in sharing his knowledge, and he and his wife, Ines, were also warm hosts when I visited Geraldton, the nearest mainland town to the Abrolhos Islands. I was in constant touch with Max throughout the course of this book and was deeply saddened when he died in mid-August 2010. Vale , Max.

And then there is the craggy cray fisherman who wishes to be known only as Spags and actually lives on those islands, loving and caring for them with an abiding passion. I met him on my visit with Hugh Edwards, and he, too, couldnt have been more generous in sharing his deep local knowledge.

In recent years, interest in the Batavia has slowly grown, and a slew of books on the subject appeared just after the millennium, as did a well-received Batavia -related opera. Yet, generally, the passion of the writers for the wonder of the story has not been remotely matched by the awareness and enthusiasm of the reading public. As I speak at various events around Australia, I frequently ask for a show of hands as to how many people know of it, and, on the east coast particularly, it is usually between five and ten per cent of the audience. The story of the Titanic is a thousand times better known.