To the Men and Women Who Made this Book Possible

Wreck hunting is an unusual occupation. As the reader will discover in the chapters to come, lost ships are found either by extensive research and field work, or in somewhat bizarre contrast they may be discovered by sheer luck and outrageous good fortune.

I have had both experiences. In the first instance the search is based on known history balanced against the challenge of a geographical unknown. This process may take years. In the second case a diver eyes wide open in amazement realizes that he has stumbled quite by accident on an old shipwreck. The discovery may take place in literally one historic moment. Then the research follows afterwards as a natural sequence.

In either case we need to know the name of the ship and the circumstances in which she was wrecked. Did her people die with her or were there survivors? In that eventuality, what was the fate of the castaways often at the end of the known earth?

And there is always the inevitable question: was she carrying gold and silver, or valuables on her fatal voyage? Chests of pieces of eight, Dutch ducatons, or Spanish silver dollars ? Treasure which might still lie in the bones of the wreck to send the heart of a discoverer beating wildly!

The research in archives, diaries and old newspapers is often an individual quest. But once an expedition takes the field it becomes a numbers game. Teamwork is the key to success and the people involved their energy, skills, companionship, and their personal contributions play an important part in the result. I have been extremely fortunate in my half century of wreck diving to be associated with some outstanding people whose efforts have resulted in triumphs for all concerned.

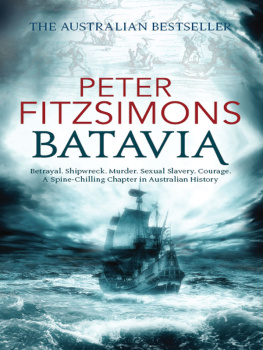

Some names spring to mind at once my newspaper comrade and cameraman Maurie Hammond; fisherman and saltwater hero Maurie Glazier; Batavia partner and Geraldton icon Max Cramer; passionate Batavia researcher and author Henrietta Drake-Brockman; and Zuytdorp author Phillip Playford; all played major roles.

The divers, the wetsuited warriors who formed our expeditions, are acknowledged too. They are noted here, sometimes with their pictures but always with their names, together with my thanks, through the pages as the chapters roll by like ocean waves.

There are also people who have been of significant importance on the book side. My sister, Elizabeth McDonald, of impeccable judgment, tested all the manuscripts. Through the years publishers Phil Mathews, Denis Cornell, Mike and Dudley Scott, James Herd, John Ferguson, Les Moss, Tom Saggers, and Jon Warren have had important roles. I am grateful for the part played by HarperCollins publishing director, Shona Martyn, associate publisher Julian Gray, senior editor Mary Rennie, and editor Russell Thomson, in this publication of Dead Mens Silver.

There were also those who kept the home fires burning while I was off and out of sight over a wave-spiked horizon. My first wife, Jennifer, and second wife, Marilyn, both displayed admirable patience and tolerance in testing circumstances. Marilyn was involved in the university Batavia expedition of 1970 and is the mother of our daughter, Petrana. Jenny is the mother of Christopher and Caroline.

As a result we now have the extended bonus of six grandchildren in Evan, Alex, Kate, Abby, Noah and Olivia. Boys and girls in equal numbers.

While there have been causes for celebration through the years, the support of the right people at the right time was always essential. Without that factor little of what the reader will discover in the following pages would have been possible.

Apart from the successes, I greatly enjoyed the company of the people concerned. Thank you one and all.

Hugh Edwards,

Swanbourne, Western Australia, 2011

Contents

Dead Mens Silver

Like so many other small boys through the years, I encountered my first pieces of eight in Robert Louis Stevensons novel Treasure Island. Wide-eyed, I drank in the adrenalin flow of adventure surging through the pages. Never dreaming that one day I would find my own pieces of eight in a 17th-century shipwreck lying at the bottom of the sea.

I identified with the young hero Jim Hawkins. Sometimes I felt that I knew Treasure Islands characters like that roguish devil Long John Silver better than some of the real flesh-and-blood people of my own acquaintance. I heard the tap-tap of his crutch a deadly weapon when he was aroused and saw the fluffed feathers of Capn Flint, the bright-eyed parrot clutching his shoulder, who was wont to lustily flap his wings and shriek Pieces of eight! Pieces of eight! at any provocation at all.

Stevensons story has become one of the best-loved British novels through the years since it was first published in 1881. It has become even more popular in modern times, with more than 50 film, television, stage, and musical adaptations, including the screen adventures of Pirates of the Caribbean.

Stevenson himself described the recipe:

Schooners, and islands, and maroons

And buccaneers and buried gold

And all the old romance re-told!

The final paragraph of Treasure Island has stayed in my own mind since I first read it. Young Jim Hawkins much older in experience than when he first shipped aboard the Hispaniola tells us:

The bar silver and the arms still lie, for all I know, where Flint buried them, and certainly they shall lie there for me. Oxen and wain-ropes would not bring me back again to that accursed island; and the worst dreams that ever I have are when I hear the surf booming about its coasts or start upright in bed with the sharp voice of Captain Flint still ringing in my ears: Pieces of eight! Pieces of eight!

When I read Treasure Island it was as a work of fiction. Certainly I never expected to find pieces of eight myself. But that would be changed forever as a diver one autumn day with a big sea rolling in from the Indian Ocean in the west. In that watery world, as my silver bubbles rose towards the surface and the surf pounded on the reef above like a roll of drums, it was as though the waves themselves were announcing, opera-style as in The Ride of the Valkyries, the start of a great new adventure. It might have been something coming straight from Stevensons own inspired pen. But what was happening here was real. The silver heavy in my hand confirmed the magic moment.

My breaths came quickly though the rubber mouthpiece gripped between my teeth. My first piece of treasure was as real as my own escalating heartbeat thudding beneath the breast of my wetsuit. And all the while my brain shouting, It cant be!

But it was no dream. No trick of the imagination. Nor was it that occasionally reported phenomenon of diving, the raptures of the deep.

The diving site was south of the small fishing village of Ledge Point on the West Australian coast, in an underwater cave below the rocky ledge of a little-known reef. Local fishermen called the reef the Three Mile, and the old Dutch of old had named it Draeckensriff (Dragon Reef) after the Vergulde Draeck (Golden Dragon) ship which was wrecked there in 1656.

A legendary East Indiaman, she was lost 124 years before James Cook sighted Botany Bay from the poop deck of the barque Endeavour, and 174 years before the first European settlers arrived on the west coast.

The better part of a lifetime later I still recall the current threatening to tear my fins off my ankles while I struggled to hold onto the muzzle of one of the Draecks cannon, fighting to stay in one spot while the fizzing spiracles of foam from the breaking waves above came reaching down from the surface.

From below they looked like dead mens crooked fingers!

A little higher on the reef face and up to the right I saw the dark mouth of the cave. I drifted into it, mouthpiece clenched between my teeth and trailing my silver hookah airline after me like an umbilical cord.