Contents

Guide

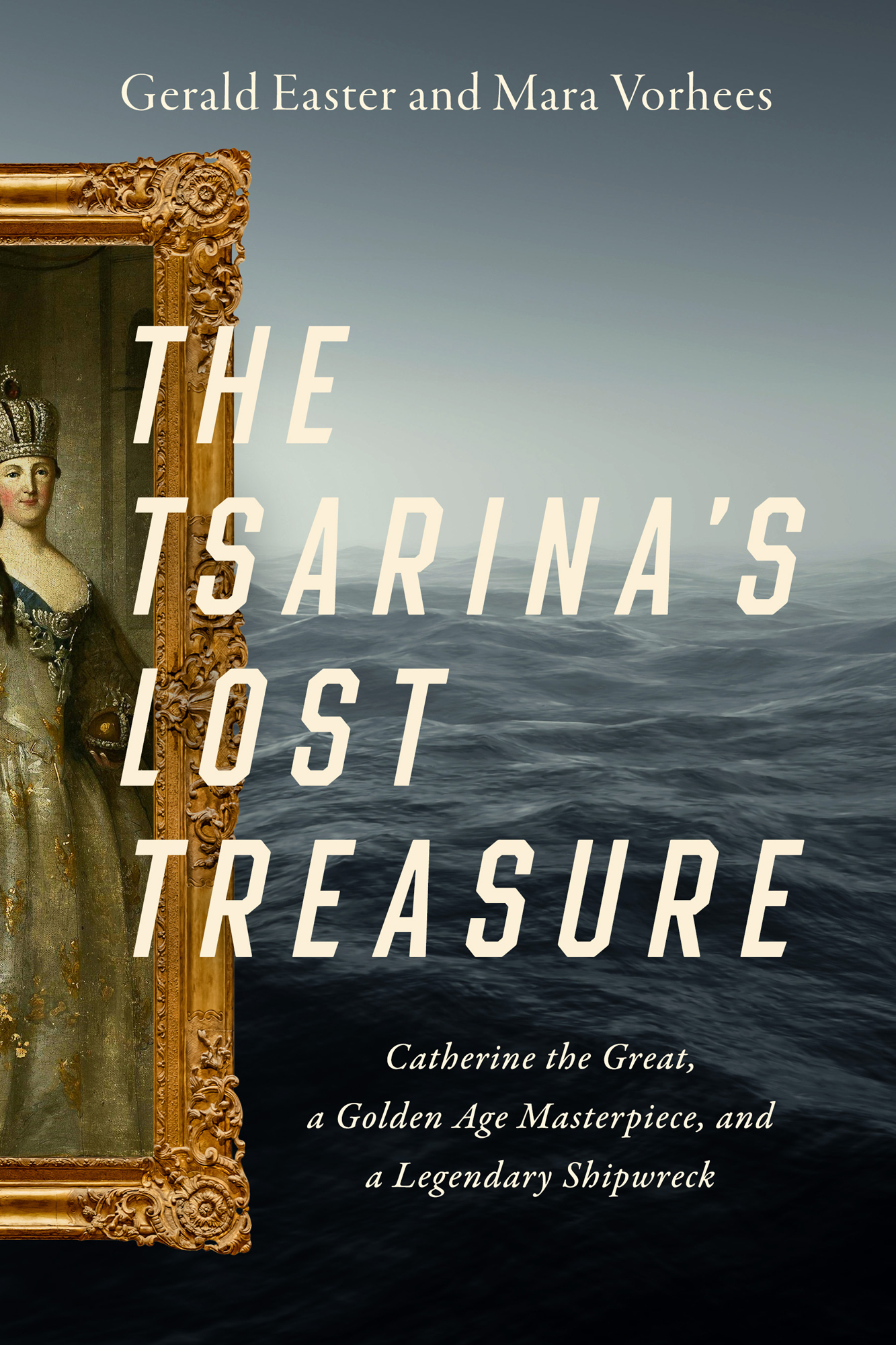

Gerald Easter and Mara Vorhees

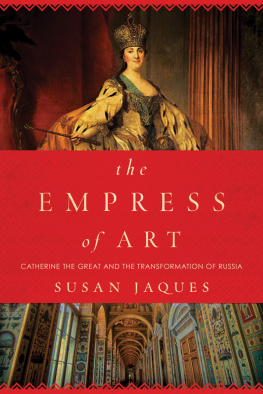

The Tsarina's Lost Treasure

Catherine the Great, a Golden Age Masterpiece, and a Legendary Shipwreck

THE TSARINAS LOST TREASURE

Pegasus Books Ltd.

148 W 37th Street, 13th Floor

New York, NY 10018

Copyright 2020 by Gerald Easter and Mara Vorhees

First Pegasus Books hardcover edition September 2020

Interior design by Maria Fernandez

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in whole or in part without written permission from the publisher, except by reviewers who may quote brief excerpts in connection with a review in a newspaper, magazine, or electronic publication; nor may any part of this book be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted in any form or by any means electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or other, without written permission from the publisher.

Jacket design: Brock Book Design Co. / Charles Brock

Cover imagery: Portrait of Catherine the Great by Ivan Argunov (17291802).

Frame & ocean: Deposit Photos

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available.

ISBN: 978-1-64313-556-4

ISBN: 978-1-6431-3557-1 (eBook)

Distributed by Simon & Schuster

www.pegasusbooks.com

For our Finnish family

Outi & Kauko Ojala

The world is full of great and wonderful things for those who are ready for them.

Tove Jansson, Moominpappa at Sea

Prologue THE WRECK

T he approaching vessel struck sail before the bronze battery, reminding all captains that further passage required payment to the Danish king. Through sallow mist the towers of Castle Kronborg loomed. The citadel of Elsinore, home to Hamlets ghosts, and gateway to the Baltic Sea.

The young skipper deliberately maneuvered his brig past Kronborgs steep sandstone walls and brawny earthen ramparts, mindful of his secret cargo. Beyond the fortress, the towns cascading red-tiled roofs and jabbing rust-green spires came into sight. The cramped harbor swayed and rattled with the spars and rigging of two dozen jostling merchant ships. English and Dutch colors snapped in the breeze. The captain secured an outlying berth and set down a launch in the direction of Tollbooth Quay, the central dock leading to the Customs House.

From King Erics time, in the 15th century, all ships passing through the Soundthe narrow strait separating Scania, the southern tip of Sweden, from Zealand, the central isle of Denmarkwere required to stop and pay an entry fee, the Sound Dues, or risk the wrath of Kronborgs gunners. Fixed between 1 and 2 percent of the value of a ships cargo, this royal protection racket was the main source of wealth of the Danish state for four centuries. The two-hundred-foot walk down Tollbooth Quay presented its own challenges as dues-paying shipmasters navigated a human surge of longshoremen at work, sailors at liberty, and thieves on the prowl. Approaching the dock, the captain clutched a leather satchel; his demeanor stiffened.

The anxious skipper was fortunate to catch the attention of one of the uniformed customs officers patrolling Tollbooth Quay, and was hurriedly escorted past the touts and thugs. Elsinore was in good form, decorated with half-timbered row houses, cobblestoned alleyways, and a newly renovated harbor front. The centerpiece was the new mansard-capped Customs House, delivered in a restrained rococo style that suited Lutheran sensibility. The captain entered and declared his business.

He was Reynoud Lourens, master of the Vrouw Maria, a merchant vessel out of Amsterdam, en route to Saint Petersburg. The ship was an eighty-five-foot snow-brig, double-masted and square-rigged. Sturdy, steerable, and spacious, the snow-brig was a favored craft among Baltic traders. A customs officer drew up a new document: Dutch ship, no. 508; September 23, 1771. From his satchel, Lourens produced an itemized cargo list and a stack of letters embossed with diplomatic stamps. Lourens was impatient to expedite the transaction. He was already a week behind schedule because of late summer winds in the Atlantic. Lourens was more so anxious about the prize hidden in the ships hold, the property of Russian empress Catherine the Great.

The officer looked down at the authoritative documents and up at the awkward captain. It was an exotic and expensive list of goods, intended to affirm the elite status of Russian high society. Sugar and coffee, indigo and brazilwood from the Americas; fine linen and woven fabric from the Low Countries; silver, zinc, and mercury for Saint Petersburgs master craftsmen; but that was not all. The officer readily surmised there was additional cargo of special interest. His inquiry met brusque resistance. It was the business of monarchs only. The Danish king was zealous about collecting the Sound Dues, except from fellow sovereigns, who were extended the courtesy of a royal exemption. Dropping the matter, the officer wrote and assorted merchandise into the ledger, then returned his attention to the cargo list. The Vrouw Maria was assessed a hefty passage bill of nearly four hundred Danish rigsdalers for the items declared. Lourens paid without protest and departed with haste.

Returning to the vessel, Captain Lourens was accompanied by a navigation pilot provided by the Customs House, a standard procedure. The crew rowed the ship away from its harbor mooring until, catching a breeze, the Vrouw Maria gained momentum. Starboard, Lourens admired the hillside rising over the town, where bursting late summer flora embraced the neoclassical Marienlyst Palace. Portside, he glimpsed a Danish Man-of-War, a fierce sixty-gun ship of the line deterrent to would-be toll evaders. The channel through the southern Sound was tapered and twisted; the pilot stayed aboard for two days until the ship reached the safety of deep water and the Baltic Sea. Lourens scrutinized the pilot as he rowed back to shore, satisfied that his secret cargo was not betrayed.

To the unsuspecting, the Vrouw Maria was an ordinary trader, hauling barrels of rye grain or salted herring. In fact, she was a treasure ship. Concealed in the hold was a cache of more than a dozen masterpiece paintings, destined for the collection of Catherine the Great. The Russian empress was unrestrained when indulging her favorite passions, one of which was art. The Vrouw Marias secret cargo was the tsarinas most recent splurge: the highest-priced items from the estate sale of renowned Amsterdam wine merchant and art collector Gerrit Braamcamp. It was the most dazzling assemblage of Flemish and Dutch Old Masters ever to reach the auctioneers block. Included in Catherines treasure trove was the auctions biggest prize, Gerrit Dous oak-panel triptych, The Nursery. Dou was Rembrandts student, who surpassed his master to become the premier artist of his time. And Dous triptych was the most admired and coveted artwork produced during the Dutch Golden Age.

Shipmaster Reynoud Lourens was only twenty-four years old. He had commanded the Russia Run three times previously, twice at the helm of the Vrouw Maria. For Dutch investors in the Saint Petersburg trade route, Lourens was valued for his experience with unpredictable Baltic tempests and petulant Russian princes. His business at the Customs House concluded, Reynoud stood braced against the laurel-carved oak rail and surveyed the stark shoreline. Along the waters edge, a clattering of jackdaws quarreled, swirled, and settled, then quarreled, swirled, and settled again as they came together for a winter roost. It was a reminder that the