CATHERINE

THE GREAT,

CEO

7 PRINCIPLES TO GUIDE &

INSPIRE MODERN LEADERS

ALAN AXELROD

STERLING and the distinctive Sterling logo are registered trademarks of Sterling Publishing Co., Inc.

2013 by Alan Axelrod

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system (or transmitted, in any form or by any means, electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise) without prior written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-4549-0561-5

For information about custom editions, special sales, and premium and corporate purchases, please contact Sterling Special Sales at 800-805-5489 or specialsales@sterlingpublishing.com.

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

www.sterlingpublishing.com

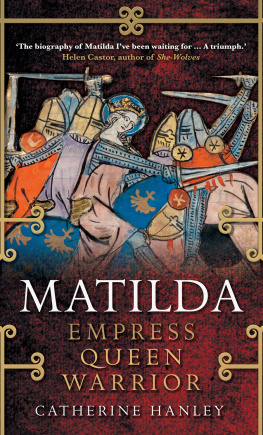

Frontispiece: Portrait of Catherine II (1763) by Russian painter Fyodor Rokotov (17361809). Picture Credits: image following cover is Courtesy of Wikimedia Foundation; dedication page: Catherine II of Russia (17291796), engraved by R. Woodman and published in The Gallery of Portraits with Memoirs encyclopedia, United Kingdom, 1835. Shutterstock/Georgios Kollidas. Chapter openers: Antique engraved portrait of Catherine the Great of Russia, iStockphoto/FierceAbin

For Anita and Ian

CONTENTS

Introduction

Whats So Great about Catherine?

Since 1999, I have written a dozen books on business leadership, based on some of historys most notable leaders. Of these, Catherine the Great, CEO is only the second devoted to a woman leader. The first was Elizabeth I, CEO.

The fact is that historians generally cite just two towering woman monarchs, Elizabeth I of England (15331603) and Catherine II of Russia (172996), invariably comparing the second to the first. That there is such a dearth of writing and research available on historical female leaders is unfortunate both for todays women leaders and for writers in search of subjects that appeal to them. The popularity of Elizabeth I, CEOa BusinessWeek bestseller in 2000attests to the vigorous demand for historical, strategic, female leadership role models. So, after twelve years, it seemed high time for another.

But is Catherine the right one?

She has certainly attracted a great deal of interest, from her own eighteenth century to our twenty-first. Most recently, she has been the subject of a major New York Times bestseller biography by Robert K. Massie (2011) and an acclaimed PBS docudrama (2006), but these are just the latest in a long succession of biographies, histories, novels, and biopics, which even include some early silent films.

Except for the most recent works, the majority of books and films devoted to Catherine have hardly focused on issues of leadership. Accounts of her harrowing adolescence and young womanhood in the court of Russias Empress Elizabeth, her arranged marriage to the psychopathic, profoundly deranged, and ineffably repugnant Grand Duke Peter (later, Czar Peter III), and her love life (more to the point, her sex life) have dominated virtually all popular and literary treatments of Catherine, including a surprising number of academic (or at least learned) studies as well.

Certainly, the sex has crowded out everything else in the purely pop culture portrait of Catherine the Great. Even during her own lifetime, Catherinethis empress who seized the throne from her husband and may even have been complicit in his murderwas often portrayed as a nymphomaniac. The scurrilous embellishments became more numerous and sensational as time went on, culminating in the persistent legend that she died trying to appease her sexual appetite by means of intercourse with a stallion. Suspended by a system of ropes and pulleys above her bed (the legend goes), the steed was lowered too quickly and crushed her to death.

Lets clear the air: This never happened.

The empress died of a cerebral hemorrhage, or strokeat the time called apoplexyand she was alone in her bedroom at the time. It is quite true that she had a lifelong passion for riding horses, and, as a superb horsewoman, she defied convention by riding astride rather than sidesaddle. While living in the court of St. Petersburg under the watchful eye of Empress Elizabeth and her many minions, Catherine even invented a unique convertible saddle. It could be configured as a sidesaddle when she set off on a hunt or a ride while Elizabeth and others looked on; and then, far from prying eyes, it could be reconfigured on the fly for riding astride. She outrode most men. Was there a sexual element in this? Well, she certainly took great pleasure in it. Did she therefore have sex with her horses? No.

As for human lovers, a dozen men have been thoroughly documented, including one she made the king of Poland, one who was her adviser at the highest level, and the redoubtable Grigory Potemkin, who was virtually her consort and may even have been secretly her wedded husband. During her own lifetime, many people in her court and throughout Europe believed she had far more than twelve liaisonsthe vast majority with very young men. During her own lifetime and afterward, she was the subject of pornographic novels, magazine stories, and engravings. Today, most reputable historians have settled on the twelve documented lovers over the course of some thirty yearsa lively but hardly sensational romantic rsum for three decades in the life of a widow.

Of course, disproving nymphomania does not in itself qualify a woman as a leadership role model. Once we have disposed of the sexual canards, we are left with what some have seen as a usurper, turned reformer, turned tyrant. No less a figure than the English poet Samuel Taylor Coleridge celebrated Catherines passing in his Ode to the Departing Year, expressing with pleasure his great relief that No more on Murders lurid face / The insatiate Hag shall gloat with drunken eye!

It is true that Catherine presided over two major wars of conquest against the Ottoman Empire. It is also true that, while she started her reign as a reformeran empress steeped in the Age of Enlightenment and one determined to bring Russia into the family of Western European nations and to exorcise the long-lingering specter of Ivan the Terribleshe later turned her back on reform and on the more liberal aspects of the Enlightenment. The reason for this retreat was the French Revolution. As it did with so many other European sovereigns, that cataclysm, which began in 1789 and lasted beyond her life and reign, struck terror into Catherines heart and mind. Fearing infection by the contagion of Jacobin extremism, anarchy, and mob rule, and loath to share the fate of Louis XVI, Catherine II became increasingly repressive in the last years of her reign. Yet she never crossed the line into outright tyranny.

Her bad yearsin the context of Russian history, hardly as bad as mostspanned 1789 to 1796. The progressive years began in 1762. For her last seven years, the best that can be said of Catherine was that she was better than all her predecessors save Peter the Great, though she was still less of an absolutist than he. For more than a quarter century of her rule, however, Catherine amply deserved the rank historians accord her, placing her alongside Austrias Joseph II and Prussias Frederick the Great as the most exemplary of the Enlightenment monarchs.

Next page