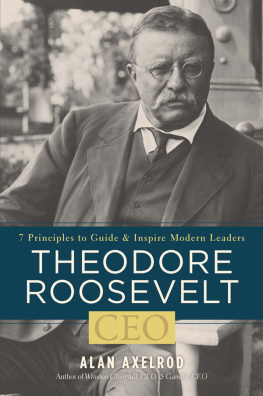

THEODORE

ROOSEVELT,

CEO

7 PRINCIPLES TO GUIDE AND

INSPIRE MODERN LEADERS

ALAN AXELROD

STERLING and the distinctive Sterling logo are registered trademarks of

Sterling Publishing Co., Inc

2012 by Alan Axelrod

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced,

stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means,

electronic, mechanical, photocopying, recording, or otherwise,

without prior written permission from the publisher.

ISBN 978-1-4027-8483-5 (hardcover)

ISBN 978-1-4027-9100-0 (ebook)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Axelrod, Alan, 1952

Theodore Roosevelt, CEO : 7 principles to guide and inspire modern leaders / Alan

Axelrod.

p. cm.

Includes index.

ISBN 978-1-4027-8483-5

1. Leadership. 2. Chief executive officers. 3. Roosevelt, Theodore, 1858-1919. I. Title.

HD57.7.A965 2012

658.4092dc23

2011033142

For information about custom editions, special sales, and premium

and corporate purchases, please contact Sterling Special Sales at 800-805-5489 or

specialsales@sterlingpublishing.com.

2 4 6 8 10 9 7 5 3 1

Courtesy Library of Congress, Prints & Photographs Division: FRONTISPIECE: President Theodore Roosevelt speaking from his car at Lake City, Minnesota, 1903 (LC-DIG-stereo-1s02081); DEDICATION PAGE: Roosevelt at his desk in the White House, c. 1902 (LC-DIG-stereo-1s01917). CHAPTER OPENERS: Engraving by Sidney L. Smith, c. 1905 (LC-DIG-pga-03324)

For Anita and Ian

While President I have been President, emphatically; I have used every ounce of power there was in the office.

~Theodore Roosevelt

He was born in the family brownstone at 28 East 20th Street, Manhattan, on October 27, 1858. From the beginning, his survival was in question. Childhood asthma, both frequent and severe, continually threatened to strangle him, so that he was unable to sleep flat in a bed, but had to prop himself on a mountain of pillows. Chronic congenital diarrheathe family termed it, more genteelly, cholera morbuscontributed to his ghostly complexion and undersized physique. That frail frame was often assailed by high fevers and racking coughs.

Physicians were doubtful that Theodore Roosevelt would reach his fourth year. But the child endured. He endured patiently at first; then, as he approached his teen years, fiercely.

When he was about twelve, his father took him aside. Theodore, you have the mindfor his son was an avid reader and a remarkably quick studybut you have not the body, and without the help of the body the mind cannot go as far as it should. You must make your body. It is hard drudgery to make ones body, father cautioned son, but I know you will do it.

Theodore promised his father and himself that he would do it, and, without hesitation, embarked on a program of exercise. Relentless walking, running, weight lifting, and calisthenics seemed destined either to build him up or lay him low. The boy worked himself daily to the very verge of collapse. As an adult, he would call this approach to living the strenuous life, and he enthusiastically recommended it to anyone who intended to make something of himself. The idea was starkly simple: use every ounce of power you had every time you did anything. If the unremitting effort threatened to kill you, so much the better. As Roosevelt would write to his friend Cecil Spring-Rice years later, Death is always and under all circumstances a tragedy, for if it is not, then it means that life itself has become one. There could be no genuine reward without real risk.

The popular mythology that has grown up around Teddy Roosevelt holds that, through dint of sheer physical and mental will, he utterly transformed himself from a sickly child into a strapping young man. The myth comes surprisingly close to realitynot that the transformation was rapid or easy, however. Even as he built himself up, relapses into asthma and cholera morbus were frequent. During a European trip with his family, Teedie (as his mother and siblings affectionately called him) started wheezing so badly that Mrs. Roosevelt confided desperately to Anna Minkowitz, who served as governess and tutor during the familys overseas sojourn, I wonder what will become of my Teedie. The young woman calmly replied, You need not be anxious about him. He will surely one day be a great professor, or who knows, he may become even President of the United States.

It was the first such prediction recorded, but certainly not the last. Even in illness, when to all appearances, the prospects for survival into adulthood were in gravest doubt, there was an air of destiny about the boy. Moreover, it clearly seemed a destiny that would be of his own making. If he could will himself to survive, he could will himself to become strong, and if he could do that, he could certainly will himself to be whatever he chose to be, including the American president.

Teedie stormed through Harvard College from 1876 to 1880, earning renown as a collegiate boxer and graduating magna cum laude, finding time as well to write his first book, The Summer Birds of the Adirondacks in Franklin County, N.Y., which was published in his sophomore year. Before he graduated, he began a second book on a very different subject, The Naval War of 1812. He studied hard. He boxed hard. The death of his father from stomach cancer on February 9, 1878, was a tough blow, but it only encouraged him to push himself harder.

Shortly after graduating, he married the beautiful Alice Hathaway Lee and then entered Columbia Law School (though he left after two years without taking his degree). He had, by this time, already thrown himself into Republican politics and, in 1881, was elected to the New York State Assembly, the youngest assemblyman in the states history.

He set out to make himself conspicuous in Albany, at first by the showy opulence of his attire, suited more to grand opera than to the legislature. A New York City dude, his legislative colleagues called him, and they snickered, even as their attention was drawn, focused, and utterly monopolized by him. From day one, freshman Roosevelt spoke up in the assembly. Within days of that first day, he was proposing legislation and was soon writing one bill after another, while also finding the time to complete and publish his book, The Naval War of 1812. That volume was instantly snapped up by the U.S. Naval Academy and assigned to midshipmen as a required textbook.

Reelected to the assembly by a margin wider than that of any other legislator in 1883, he was named minority leader, and, after touring the slums of New York City with union organizer Samuel Gompers, composed and championed a series of groundbreaking public welfare bills. Then, when the assembly recessed, he went out Westway out west, to the Dakota Territory Badlands, bought two ranches there, and worked them alongside the other cowboys, taking time off to hunt bison on the prairie.

Next page