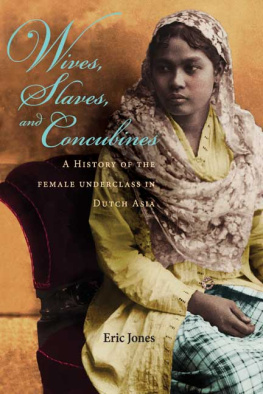

Eric Jones - Wives, Slaves, and Concubines: A History of the Female Underclass in Dutch Asia

Here you can read online Eric Jones - Wives, Slaves, and Concubines: A History of the Female Underclass in Dutch Asia full text of the book (entire story) in english for free. Download pdf and epub, get meaning, cover and reviews about this ebook. year: 2011, publisher: Cornell University Press, genre: Home and family. Description of the work, (preface) as well as reviews are available. Best literature library LitArk.com created for fans of good reading and offers a wide selection of genres:

Romance novel

Science fiction

Adventure

Detective

Science

History

Home and family

Prose

Art

Politics

Computer

Non-fiction

Religion

Business

Children

Humor

Choose a favorite category and find really read worthwhile books. Enjoy immersion in the world of imagination, feel the emotions of the characters or learn something new for yourself, make an fascinating discovery.

- Book:Wives, Slaves, and Concubines: A History of the Female Underclass in Dutch Asia

- Author:

- Publisher:Cornell University Press

- Genre:

- Year:2011

- Rating:4 / 5

- Favourites:Add to favourites

- Your mark:

Wives, Slaves, and Concubines: A History of the Female Underclass in Dutch Asia: summary, description and annotation

We offer to read an annotation, description, summary or preface (depends on what the author of the book "Wives, Slaves, and Concubines: A History of the Female Underclass in Dutch Asia" wrote himself). If you haven't found the necessary information about the book — write in the comments, we will try to find it.

Wives, Slaves, and Concubines argues that Dutch colonial practices and law created a new set of social and economic divisions in Batavia-Jakarta, modern-day Indonesia, to deal with difficult realities in Southeast Asia. Jones uses compelling stories from ordinary Asian women to explore the profound structural changes occurring at the end of the early colonial periodchanges that helped birth the modern world order. Based on previously untapped criminal proceedings and testimonies by women who appeared before the Dutch East India Companys Court of Alderman, this fascinating study details the ways in which demographic and economic realities transformed the social and legal landscape of eighteenth-century Batavia-Jakarta. Southeast Asian women played an inordinately important role in the functioning of the early modern Asia Trade and in the short- and long-term operations of the Dutch East India Company (VOC). Southeast Asia was a place where most individuals operated within an intricate web of multiple, fluid, situational, and reciprocal social relationships ranging from dependence to bondedness to slavery. The eighteenth century represents an important turning point: the relatively open and autonomous Asia Trade that prompted Columbus to set sail had begun to give way to an age of high imperialism and European economic hegemony. How did these changes affect life for ordinary women in early modern Dutch Asia, and how did the transformations wrought by Dutch colonialism alter their lives? The VOC created a legal division that favored members of mixed VOC families, those in which Asian women married men employed by the VOC. Thus, employmentnot racebecame the path to legal preference, a factor that disadvantaged the rest of the Asian women. In short, colonialism created a new underclass in Asia, one that had a particularly female cast. By the latter half of the eighteenth century, an increasingly operational dichotomy of slave and free supplanted an otherwise fluid system of reciprocal bondedness. The inherent divisions of this new system engendered social friction, especially as the emergent early modern economic order demanded new, tractable forms of labor. Dutch domestic law gave power to female elites in Dutch Asia, but it left the majority of women vulnerable to the more privileged on both sides of this legal divide. Slaves fled and violence erupted when traditional expectations of social mobility collided with new demands from the masters and the state.

Eric Jones: author's other books

Who wrote Wives, Slaves, and Concubines: A History of the Female Underclass in Dutch Asia? Find out the surname, the name of the author of the book and a list of all author's works by series.