THE LOST LEGIONS OF

FROMELLES

The mysteries behind one of the most devastating battles of the Great War

PETER BARTON

Translations from the original German by Michael Forsyth

Constable London

For Hester, Stanley, Victor and Kitty

Constable & Robinson Ltd.

55-56 Russell Square

London WC1B 4HP

www.constablerobinson.com

First published by Allen & Unwin, Australia, 2014

This paperback edition published in Great Britain in 2014 by Constable

Copyright Peter Barton, 2014

The moral right of the author has been asserted.

All rights reserved.

No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form, or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of the publisher, nor be otherwise circulated in any form of binding or cover other than that in which it is published and without a similar condition including this condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser.

A CIP catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library.

ISBN 978-1-47211-712-0 (Trade paperback)

ISBN 978-1-4721-1937-7 (ebook)

Typeset in 11/15pt Minion by Midland Typesetters, Australia

Printed and bound in Great Britain by Mackays

CONTENTS

LIST OF MAPS

Text maps

Map colour section

Map 1: Theatres of war in Western Europe and the Middle East

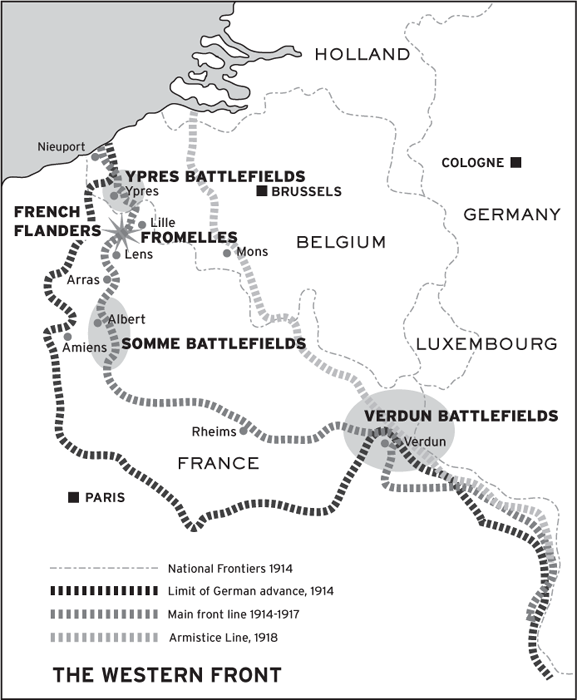

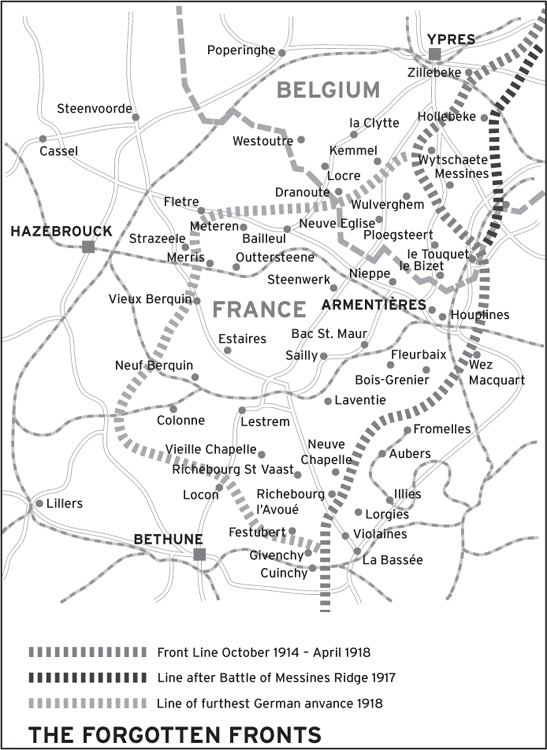

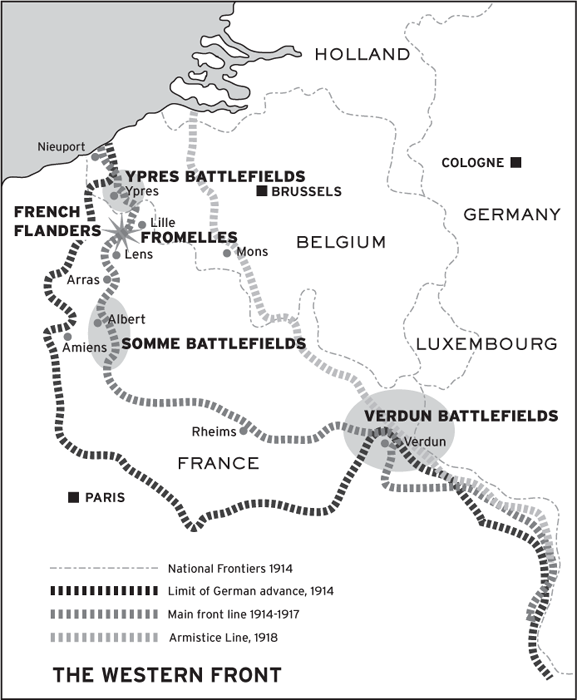

Map 2: The Western Front showing the major battlegrounds. Fromelles is in French Flanders.

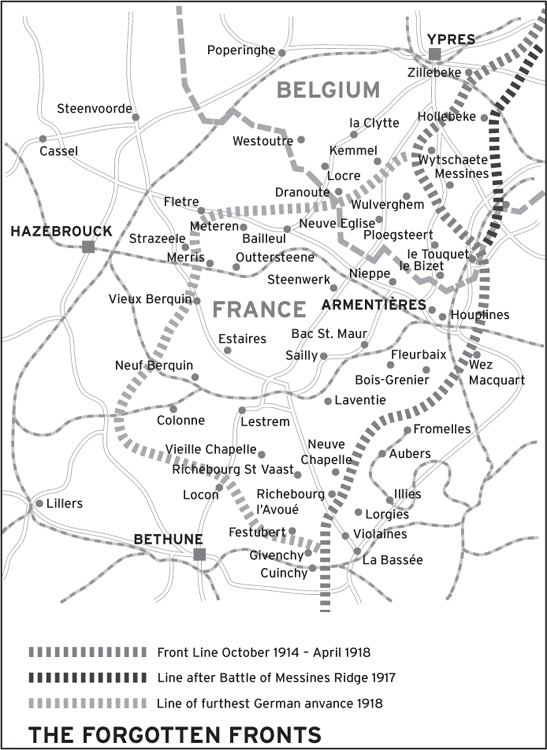

Map 3: The towns and villages of French Flanders, and the positioning of the front line between September 1914 and November 1918.

PREFACE

On the way back we spent some time in the old No Mans Land of four years duration, round about Fauquissart and Aubers. It was a morbid but intensely interesting occupation tracing the various battles amongst the hundreds of skulls, bones and remains scattered thickly about. The progress of our successive attacks could be clearly seen from the types of equipment on the skeletons; soft caps denoting 1914 and early 1915, then respirators, then steel helmets marking attacks in 1916. Also Australian slouch hats, used in the costly and abortive attack in 1916. There were many of these poor remains all along the German wire.

Major Phillip Harold Pilditch, Royal Field Artillery,

The War Diary of an Artillery Officer, 19141918

It was on Thursday 30 July 1914 that warning telegrams from London arrived in Melbourne and Wellington: a European war against Germany and AustriaHungary appeared unavoidable; Britain was mobilising. Three days later Australia followed suit, placing her forces on a war footing and activating coastal defences. By the evening of 6 August Australia and New Zealand had both offered an Expeditionary Force. Having converged upon King George Sound at Albany, Western Australia, on 1 November 1914 the initial convoy of twenty-eight troop ships set sail, striking out towards the first military action of the recently federated Commonwealths. The ripples from their bow waves still lap upon the shores of Australasia. Their final destination was not to be, as all on board expected and probably desiredFrancebut the Gallipoli Peninsula, a Turkish battleground on the very seam of Europe and Asia. There they would for eight months struggle alongside French, British and Indian allies in a calamitous campaign that achieved no strategic benefit for either the Empire or the Entente.

Meanwhile, on the Western Front, Britain, India, Canada and France were suffering a chain of revelatory malfunctions. After Gallipoli, the men of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) reorganised, reinforced and reconditioned in Egypt, and prepared themselves for their opening engagement in France, an assault that began at 6.00 p.m. on 19 July 1916 near the small village of Fromelles. Although the Somme, Arras, Passchendaele and the great and crucial clashes of 1918 were still part of an unimaginable future, the subsequent fourteen hours of vicious combat were to prove the most catastrophic of the one thousand days of Anzac presence on the Western Front.

And so from the vast and distant universe that was Australia, with all its air, light and prosperity, the Diggers were flung into the foul gutter of Flanders, again to struggle alongside the British Tommies. Life in the trenches was a strange blend of boredom, dread, uncertainty, discomfort, hard labour, violence and sudden death that demanded a peculiar fortitude to endure with sanity intact. Hope seldom entered the equation. Men were by necessity fatalistic, and yet supported by a tide of intimate and deeply cherished comradeship that the presence of mutual mortal danger engendered and cultivatedmateship, in the Australian vernacular. It was the first time that most of the middle- and upper-class soldiers had been pressed into close living proximity with workers and labourers. The enforced intimacy generated degrees of understanding that had never before existed, or indeed been able to exist; it was an understanding that frequently led to profound respect. Partly in this manner, the Great War began to change the social structures of a score of nations.

In 1919, for both Australian and Briton, there was a harsh homecoming. The war had almost bankrupted that seemingly invulnerable edifice, the British Empire. Civilian life was altered, and work hard to find. The personal legacy of the war was profound. For legions of men the mental and physical consequences of the conflict would remain all their lives. In the Britain of the 1960s there were still hospital wards filled with uncured and incurable victims. The last of them, Private David Ireland of the Black Watch, died in Scotland in 2001; he had been in psychiatric care since 1924seventy-seven years.

As ever, for such is human nature, in all the belligerent nations buoyancy and optimism returned. The cadence of normal life resumed, and with it came the sense of a more certain future. For many families, however, a particular form of nightmare persisted. Every theatre of conflict concealed a multi-national lost army. Along the thin ribbon of Europe that had so recently been the Western Front, in 1919 there still lay unfound the remains of half a million soldiers. No family ever surrendered the hope that one day the body of their man, their boy, their child, would be recovered and given a grave, a grave that might be visited. And yet after the Armistice of November 1918 the search for the missing was officially drawn to a close within thirty-six months, far sooner than most had anticipated. It was a decision that brought anguish, anger and misery, leaving a void in the lives and hearts of millions. The Fromelles Project, which began in 2006 with the scrutiny of a piece of French pastureland and ended in 2010 with the exhumation and reburial in a new cemetery of the 250 soldiers found there, has shown that that void endures until through knowledge generations long dislocated are reconnected with the true legacy of war: irreplaceable human loss. That recognition frequently seeds the demand to know and understand, but like the poppy, conditions must be perfect before germination can occur. Above all, the ground in which that seed lies must be regularly disturbed.