SIMON CAMERON

Copyright Simon Cameron

First published 2013

Copyright remains the property of the authors and apart from any fair dealing for the purposes of private study, research, criticism or review, as permitted under the Copyright Act, no part may be reproduced by any process without written permission.

All inquiries should be made to the publishers.

Big Sky Publishing Pty Ltd

PO Box 303, Newport, NSW 2106, Australia

Phone: 1300 364 611

Fax: (61 2) 9918 2396

Email: info@bigskypublishing.com.au

Web: www.bigskypublishing.com.au

Cover design and typesetting: Think Productions

National Library of Australia Cataloguing-in-Publication entry

Author: Cameron, Simon, author.

Title: Lonesome pine : the bloody ridge / Simon Cameron.

ISBN: 9781922132307 (paperback)

Notes: Includes bibliographical references.

Subjects: Australia. Army. Australian and New Zealand Army Corps--History.

World War, 1914-1918--Campaigns--Turkey--Gallipoli Peninsula.

Gallipoli Peninsula (Turkey)--History, Military--20th century.

Dewey Number: 940.426

To Jennifer, my most dedicated proof reader.

TABLE OF CONTENTS

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Australian war history is always indebted to our first war historian, Dr Charles W Bean for his tireless efforts in documenting and preserving Australian war history. The Australian War Memorial is his unique legacy and the ever helpful archivists of that institution receive my thanks.

Special thanks to Dr Simon Benger, School of Environment, Flinders University for assisting with the production of the 3D images of the plateau, with graphic design and drawing of these two maps provided by Saxon Cameron.

Mr Patrick Gariepy has taken on the herculean task of documenting the Gallipoli casualties and his assistance has been invaluable to this work.

Thanks to Big Sky Publishing for their editorial and map drawing skills, and to my family for their endless proof reading.

Simon Cameron

PROLOGUE

Captain Alfred Shout drifted in a sea of morphine, strapped to a stretcher that was tied securely to deck rings. The sea washed against the shingle, and the gentle rise and fall of the Aegean swell rocked the barge. He was flanked by other stretchers and sounds fumbled through his thoughts. Voices rose up and down like the waves. In the distance he heard the steady crump of guns spitting star shells, and closer, the chug of steam pistons.

Shout was leaving Gallipoli on a small steam lighter carrying him to a waiting hospital ship. The stump of his arm, shredded by a bomb blast, was swaddled. He could just make out a starlit sky through the sticky bandage wrapping his face. Shout was content. His men had told him that Lonesome Pine was theirs for good. Good old First Brigade. Well done! were his last recorded words.

One day and a lifetime ago Shout had commanded his company of the 1st Battalion, holding grimly to the captured Turkish trenches of Lone Pine. It was his third day of fighting and only a handful of men were still able to stand, but the fight was nearly spent. In one of an endless series of assaults the Turks had broken through the sandbag barriers to retake 50 metres of hard-won trench, and Shout was determined to bomb them out. He had done it before. This time he roared with excitement as he made the final rush, following his riflemen along the trench, stepping over bodies, fallen sandbags and broken rifles. Nearly at the final barricade, he lit three bombs throwing one and then another. The last fuse was too short and the explosion tore off his hand and peppered his neck and face.

Born in New Zealand, and battle tested in the Boer War, Alfred Shout was like so many of the first Anzacs. They came from all parts of the Empire and considered themselves British. He joined the militia soon after he moved to Australia in 1907.

Aged 34, Lone Pine was his second great battle. At the April landing he won the Military Cross, crawling forward to help the 2nd Battalion establish a defensive position along the second ridge line; a position that would soon become known as The Nek. Those anxious, exhausting days after the landing had slipped by without serious mishap for Alfred Shout, but two weeks later a Turkish sniper had drilled through his arm and into his chest. Two months later and promoted to captain he was ready to lead his 1st Battalion Company across no-mans-land against the Turkish stronghold at Lone Pine located on a second ridge top plateau, staying resolutely with them until that final rush along the trench.

Shout was stretchered from Gallipoli believing the job had been well done. He made it to the hospital ship Neuralia one of an avalanche of wounded, but his blood loss had not been stopped. How and where he died was not recorded. Sewn into his blanket he was slipped off his stretcher into Homers wine dark sea. Just one of many, his fate was almost unnoticed but for a brief note on the consignment list; a fate that remained uncertain to his wife Alice and daughter Florence, who waited in Darlington for news. He was wounded they were told. He had died. No, he was coming home, dressed and dispatched. And then finally we regret to confirm he succumbed.

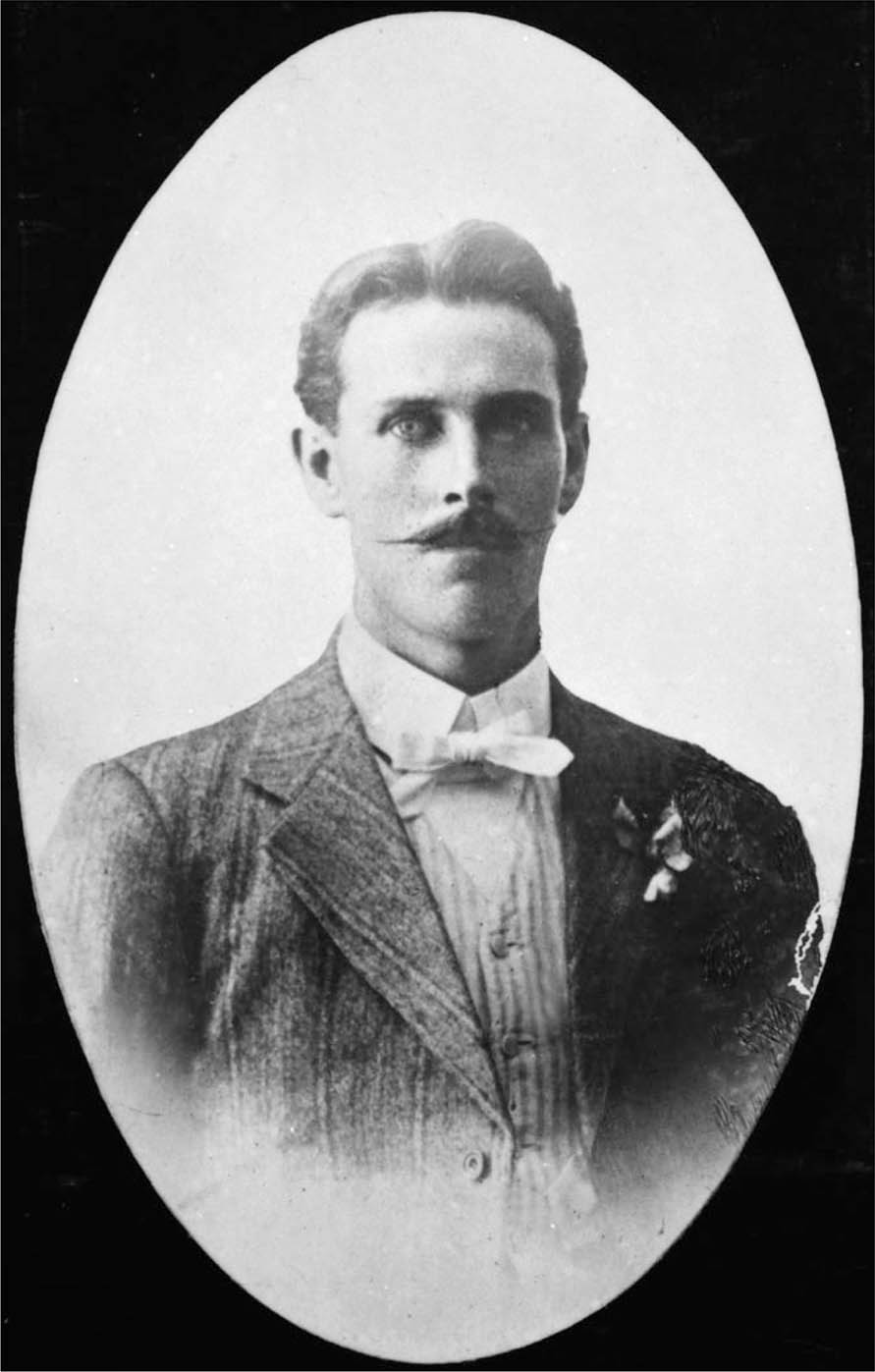

Captain Alfred Shout VC studio portrait. AWM P02939.003

On Gallipoli they knew his fate at the end of August and his fellow officer in the final rush, Captain Cecil Sasse, had already made sure Alfred Shouts loss would not be forgotten. The storming of the trench was one of the last actions at Lone Pine. Soon after that final rush the new battleline was drawn and the trench siege renewed. Shouts wild dash won him a Victoria Cross, and together with his military cross and a mention in dispatches he became the most highly decorated Australian on the peninsula. And as extraordinary as his feat was, his Victoria Cross was only one of seven awarded for the fighting on the little hill plateau called Lone Pine.

INTRODUCTION

To the Australian public Gallipoli means Anzac Day and the storming of coastal cliffs. All would know why the Turks were involved they were defending their home soil. But understanding why Australians were fighting their way up these particular cliffs would be a challenge to most. Earlier generations knew that it was all to do with the Dardanelles and seizing of the exotic city, Constantinople. This city had ceased to exist with the Turkish conquest 400 years earlier, becoming Istanbul instead, but Constantinople was a name too strongly engraved in the classical imagination of Western Europe to lose its lure.

During World War I, the then Ottoman Empire sided with Germany. The allies strategy was simple. The aim was to knock the belligerent Turkish Empire out of the war and open sea access to allied Russia, via the Bosporus and Sevastopol. The British and French navies believed they could blast their way through the narrow straits known as the Dardanelles, steam on to Constantinople and bombard it into submission. The fleets had to first brave the coastal forts and gun emplacements, and then clear minefields. They made the final all out attempt on 18 March 1915 and lost three battle ships with little to show for it. Mines were the major obstacle in the narrow straits, but for minesweepers to work effectively the guns along the western shore of the Dardanelles, on the Gallipoli Peninsula, would have to be silenced.

Next page