The whole Allied front was barely four miles, swept by a terrible inferno of shells. The air was filled with the white, woolly clouds that the Anzac menold soldiers nowknew meant a hail of lead.

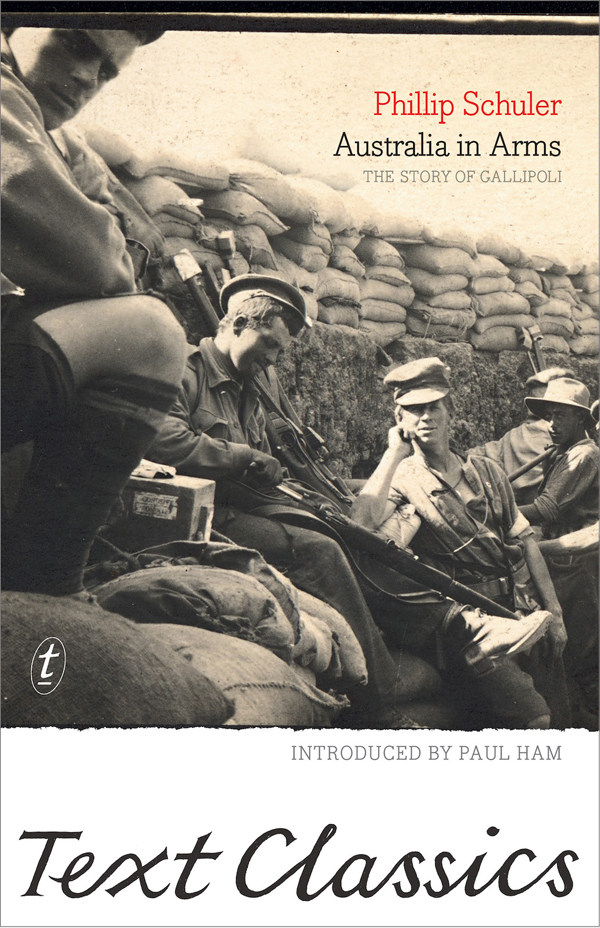

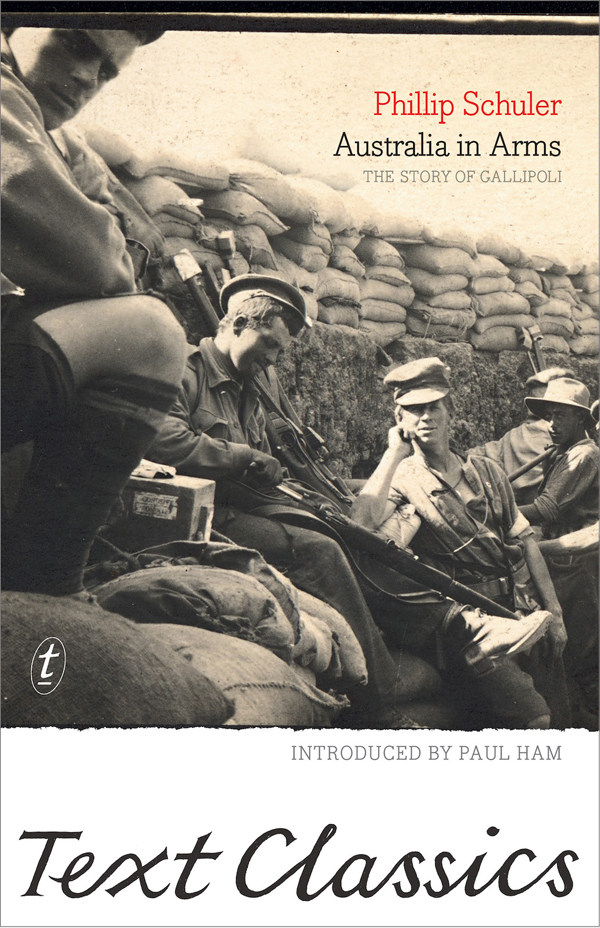

First published in 1916, Australia in Arms is a vital early account of the Gallipoli campaign. The young journalist Phillip Schuler, later killed in battle, witnessed the whole of the August offensive from...trenches at Lone Pine. He saw the valour of the Anzacs, and recognised too the strength of their Turkish opponents.

Vivid and incisive, his is one of the finest achievements of Australian military writing.

Remarkably fresh, compelling and dispassionate. Mark Baker

The visionary Diana Gribble founded Text in 1990. She wanted to create an independent publishing house that would find books to enlighten, challenge and entertain us. In keeping with this vision, Text Classics are books by our most loved writers who tell our stories.

textclassics.com.au

PHILLIP FREDERICK EDWARD SCHULER was born in Melbourne in 1889. He was the only son of Frederick Schuler, the German-born editor of the Age from 1900 to 1926.

After completing compulsory military service, Phillip Schuler became a junior reporter at the Age. He volunteered in 1914 to sail to Egypt as the newspapers war correspondent and photographer. En route, he became friendly with Australias official war correspondent, C. E. W. Bean. In 1915 Schuler travelled to Turkey, where he was embedded with Anzac soldiers and filed a series of reports.

On his return home he wrote Australia in Arms: A Narrative of the Australasian Imperial Force and Their Achievement at Anzac, the first full-length account of Australias role in the Gallipoli offensive, and the short illustrated work The Battlefields of Anzac. General Sir John Monash called Australia in Arms the best and fullest storyof the whole Anzac campaign.

By the time the books were published, in 1916, Schuler had enlisted with the AIF. He was swiftly promoted and sent to Europe.

Phillip Schuler died in 1917 of injuries sustained in the Battle of Messines, Belgium. Beans obituary described him as brilliantly handsome, bright, attractive, generous. He is remembered as a pioneering Australian war reporter.

PAUL HAM lives in Sydney and Paris. For many years he was the Australian correspondent for the London Sunday Times. His acclaimed books include Kokoda, Vietnam: The Australian War, Hiroshima Nagasaki, Sandakan and Young Hitler: The Making of the Fhrer. Among his World War I works are 1914: The Year the World Ended and Passchendaele: Requiem for Doomed Youth.

CONTENTS

BETWEEN the covers of Australia in Arms you will find that rarity in our unchivalrous age: an account of Gallipoli by a young war correspondent who believed in notions of gallantry, liberty, heroism and self-sacrifice. He followed the men into the breach to tell their story, and then, slightly ashamed of being a mere scribbler, enlisted in the infantry.

Phillip F. E. Schuler was shot dead in Flanders in June 1917, just before the battle of Passchendaele. He was twenty-seven. He left behind this minor classic of the Gallipoli campaign, published a year earlier.

Schuler came from a prosperous literary family. His father was the editor of the Melbourne Age, which eased the lads path to selection as a war reporter, and helped him secure a front-row seat at Gallipoli in 1915. He worked and played alongside the great Charles Bean, the official war correspondent. They met on board the Orvieto and visited the pyramids together. Bean would describe Schuler, after he was killed, as a brilliantly handsome, bright, attractive, [and] generous youngster.

The extraordinary thing about Schulers account of the Dardanelles is that it expresses without a trace of criticism or mockery the British and colonial effort at Gallipoli. Here is a man who utterly believed in the war and the men who led it. Most of the commanders he loved and respected. For him, the cause was right; the ends, just.

He was there during the journey out (where he witnessed the sinking of the Emden), at the Gallipoli landings, the battles of the Nek, Quinns Post and Lone Pine, the charge of the Australian Light Horse and other fabled moments in the doomed invasion. And at the end of it all this young man was still able to see the battle not only as a worthwhile expression of duty done, but also as the forging of the nation: Australia, he writes,

attained Nationhood by the heroism of her noble sons. Anzac will ever form the front page in her history, and a unique and vivid chapter in the annals of the Empire. The very vigour of their manhood, the impetuosity of their courage, carried slopes that afterwards in cold blood, seemed impregnable.

Schuler is unflinching in his belief in the rightness of the Mother Country and in the sincerity with which he seeks to wrap the young Australian nation in the image of Anzac. It never occurs to him to question that duty, to ask why Australia should have followed Churchills crackpot plan, to invade the Turkish nation on the orders of Britain in an attempt to open a third front against Germany. Churchill rates just one mention in the book.

But we should not ask for such things in a work like this. It is not an analysis. It is reportage, written with sensitivity, awe and respect, by a man of his time. It is a historically accurate reflection of the ideals and feelings of most men and women of 1915, told in a voice that is at once sincere and ingenuous.

We are in Schulers debt for that voice. It is authentic. His words cement the point that many Australians were conscious that they were building a new country in the crucible of war. That was not some pseudo-nationalist sentiment superimposed on Gallipoli with hindsight. In 1915 it was real; it was felt. And this authenticity deserves respect, whatever else you might feel about the project of trying to embed national identity in a military catastrophe.

Schuler was a journalist, not a historian, and yet his action-packed account of Gallipoli may indeed be read as the first draft of history. It is laden with vivid anecdote and well-chosen detail. Take his description of a crowd of enlisted men about to march off to war. He conjures the social gradations of an entire army through a snapshot of how they were shod and dressed:

There were men in good boots and bad boots, in brown and tan boots, in hardly any boots at all; in sack suits and old clothes, and smart-cut suits just from the well-lined drawers of a fashionable home; there were workers and loafers, students and idlers, men of professions and men just workers, who formed that force. Butthey were all fighters, stickers, men with some grit (they got more as they went on), and men with a love of adventure. So they marched out to their camp at Broadmeadowsa good ten-mile tramp.

Schuler is unsparingly admiring of the Australian soldier, who was generous to a fault and spoiled the local Egyptians. Even on leave, when many Aussies were busy establishing their reputations as larrikinsthe timeless euphemism for drunken whore-mongering loutsthe diggers were merely indulging in good old-fashioned masculine fun, the locker-room talk of 1915, innocent for the most part. Hence Cairo was

an orgy of pleasure, which only a free and, at the time, unrestrained citycould provide. Those men with 10 to 20 in their pockets, after being kept on board ship for two months, suddenly to be turned loose on an Eastern townhealthy, keen, spirited, and adventurous menit would have been a strong hand that could have checked them in their pleasures.

Next page