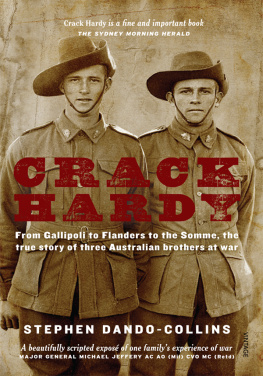

About the book

Stephen Dando-Collins skilfully braids together the Searle brothers' story and that of Australia in the Great War, balancing the family's experience and tragedy against the broader canvas of a nation's war

DR PETER STANLEY

'Crack hardy' grin and bear it, put on a brave face was a saying among Australian and New Zealand soldiers in the First World War trenches. This is the true story of three of those Australian soldiers, the Searle brothers. One brother was killed at Gallipoli, another on the Western Front. One came home a decorated hero.

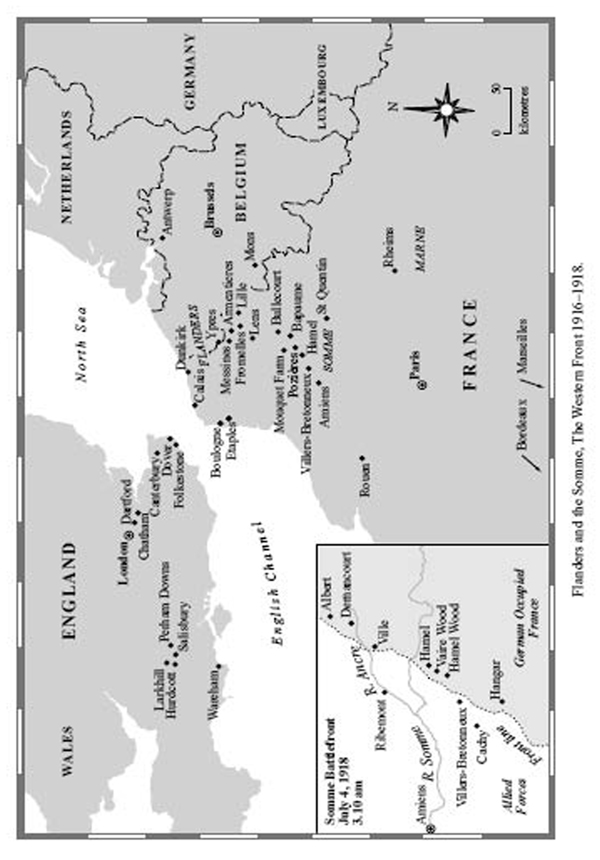

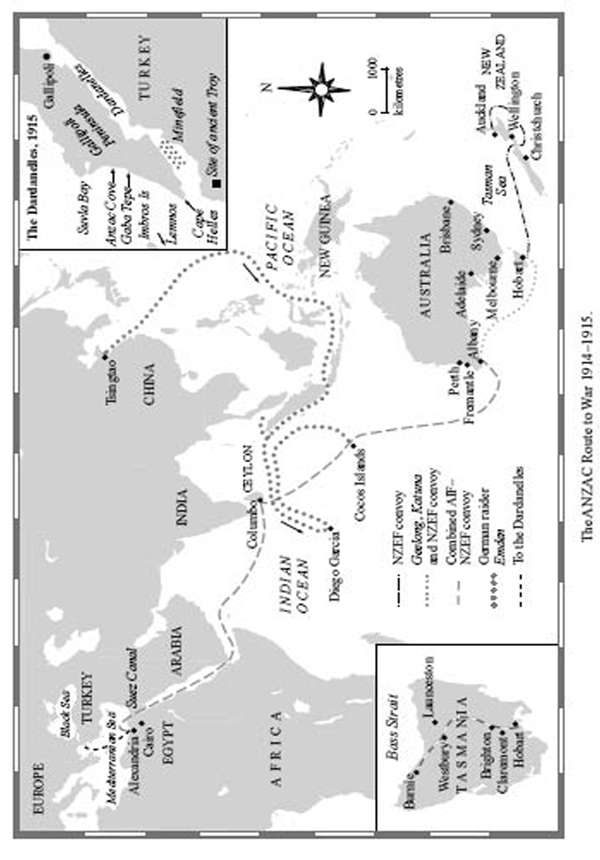

The Searle boys had to crack hardy, as they fought in one gruelling campaign after another from the first wave of the Gallipoli landings to Lone Pine, from Ypres to Messines and Hill 60 in Flanders, to bloody battles on the Somme at Mouquet Farm, Bullecourt, and Hamel, with their brothers and mates falling all around them.

Told from the heart by the Searle brothers' great-nephew, award-winning author Stephen Dando-Collins, using the letters and journals of the Searle brothers and remembrances of other family members, Crack Hardy is a compelling book that defines Australia and Australians during the making of our nation on the far flung battlefields of the First World War.

Es laughed, an told me stories uv the war.

Changed some, e looked, but still the same ole Mick,

Keener an cleaner than e wus before.

Es took me and, an said es in great nick.

Sich wus the dreamins uv a fool oo tried

To jist crack ardy, an old gloom aside.

C.J. Dennis, The Moods of Ginger Mick , 1916

Wellington once said, Next to a battle lost, the greatest misery is a battle won. Crack Hardy is a beautifully scripted expos of one familys experience of war. The intimacy and accuracy of the Searle brothers story does not glamorise conflict but poignantly illustrates the actions men take and the emotions they feel when confronted with the brutal circumstances of combat. Stephen Dando-Collins can rest assured that not only do the spirits, memories and history of his great-uncles live through this tale, but also those of their comrades in arms and the families that loved them. Like Faceys A Fortunate Life , this book deserves to be required reading as part of the Australian history school curriculum.

Major General Michael Jeffery

AC AO (Mil) CVO MC (Retd)

VIV, RAY AND NED Searle were my great-uncles. Their sister Doris was my grandmother, and her daughter Gwen, my mother. For years, I wanted to tell their story. Yet, it was too personal, too painful. In 1914, all three of the boys, as Ive always thought of them, left the Australian country town where they were raised, to volunteer to fight in the First World War. Between 1915 and 1918 they fought in many major battles, from Gallipoli to the Western Front. Two brothers died in those battles. Only one came home, returning a decorated hero.

Even when the diaries and letters of the boys were unearthed in 1991, I resisted the temptation to write about them, despite the fact that their words made the trio and their trials and tribulations so real to me. Especially when the discovery of those documents prompted my mother to share memories of her uncles, aunts and grandparents with me at length. But still I held back. Then, several years ago, while researching another book in Canberra, my wife Louise and I paid a visit to the Australian War Memorial, Australias shrine to the men and women who have given their lives in numerous conflicts since the nineteenth century. And that day, everything changed.

It was in the War Memorials Commemorative Area. Four fuzzy-wuzzies, Papua-New Guinea natives, stood staring at us. Three were dressed in smart business suits, shirts and ties, but all wore traditional feather headdresses. One carried a tribal drum, and was entirely in native New Guinea attire, with a long boar-teeth necklace draped around his neck and a wooden spear in his left hand. His youthful, trim brown body seemed at odds with his long white beard. All four looked at Louise and myself as if this place was, to them, spooky, like a giant graveyard.

The New Guinean men had apparently come to pay their respects to the World War Two diggers who had fallen in their homeland fighting the Japanese invader. Perhaps, too, they were honouring the Australians who wrested German New Guinea from German control in 1914 during the early days of World War One. The PNG men parted to let us pass, but did not take their eyes off us. It was as if they wanted to tell us something. Yet they did not speak, and nor did my wife or myself.

I was single-minded in my quest for a pair of names among those of the 60,000 First World War Australian dead on the walls here, the names of two of my great-uncles. I found one name quite quickly, at chest height, and adorned it with one of two red crepe poppies I had purchased for a couple of dollars in the AWM shop. The other name evaded me. A young man appeared at my side. An employee of the War Memorial, he knew by the poppy in my hand that I had come in search of a relative. In his twenties, round-faced, with glasses, the young man asked politely, reverently, who I was searching for, and the number of his battalion. I gave him both, and he helped me locate the name of the second of my great-uncles. It was high up, well out of reach, so the young man bustled away, to soon return with a stepladder.

My helper held the ladder as I climbed it. And then I was face-to-face with the name of my maternal grandmothers brother. When he died, he would have been younger than the kindly youth holding the ladder for me. Slowly, I traced my fingers over the raised bronze print of my great-uncles name, and as I did, to my surprise, I began to choke up. I had never known him; he had died long before I was born. Yet, here I was, feeling as if I was meeting him for the first time, as if he was here, living, in this wall. Overwhelmed with sadness, I jammed the poppy into the wall beside his name.

Step by aluminium step, I returned to the ground. Louise said something to me, but I couldnt respond. She thanked the young man for his help, and firmly took my arm. With measured paces we began to walk away together. The fuzzy-wuzzies were ahead. Again they parted to let us by. After we had passed them, I felt the need to look back. We stopped, and turned. The gaze of the fuzzy-wuzzies had followed us. They still bore that same expression. It was as if they had seen a ghost. Or ghosts.

Was it my vivid imagination, or was I now seeing figures behind the fuzzy-wuzzies? My two great-uncles. And, clustered behind them, hundreds, thousands of other washed-out young men in khaki. Some were leaning on the shoulders of their mates. All were watching me. There was a look of expectation on their pale, innocent faces.

It was then that I made a promise to my great-uncles that, one day, I would tell their story, and the story of their mates. Their true story. As best I could.

Next page