The Supermodel and the Brillo Box

The Supermodel and the Brillo Box

Back stories and Peculiar Economics from the World of Contemporary Art

Don Thompson

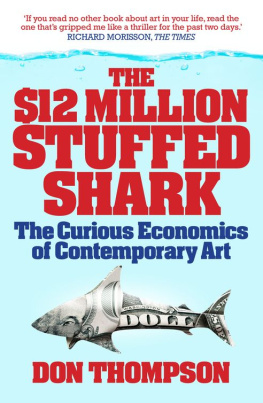

From the author of

The $12 Million Stuffed Shark: The Curious Economics of Contemporary Art

THE SUPERMODEL AND THE BRILLO BOX

Copyright Don Thompson, 2014.

All rights reserved.

First published in 2014 by PALGRAVE MACMILLAN in the United Statesa division of St. Martins Press LLC, 175 Fifth Avenue, New York, NY 10010.

Where this book is distributed in the UK, Europe and the rest of the world, this is by Palgrave Macmillan, a division of Macmillan Publishers Limited, registered in England, company number 785998, of Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire RG21 6XS.

Palgrave Macmillan is the global academic imprint of the above companies and has companies and representatives throughout the world.

Palgrave and Macmillan are registered trademarks in the United States, the United Kingdom, Europe and other countries.

ISBN 978-1-137-27908-8

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Thompson, Donald N.

The supermodel and the Brillo box : back stories and peculiar economics from the world of contemporary art / Don Thompson.

pages cm

Includes bibliographical references.

ISBN 978-1-137-27908-8 (alk. paper)

1. Art, Modern21st centuryEconomic aspects. 2. ArtMarketingHistory21st century. 3. ArtCollectors and collectingPsychology. I. Title.

N6490.T528 2014

709.05dc23

2013036143

A catalogue record of the book is available from the British Library.

Design by Letra Libre, Inc.

First edition: May 2014

10 9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1

Printed in the United States of America.

Contents

The Colors of Contemporary Art

Collecting and Investing

The Contemporary Artists

The Auction Houses

The Art Dealers

Changing Markets

The Market as Medium

Postscript and References

Stephanie

Great art is when you just walk round a corner and go: F hell! Whats that?

Damien Hirst, artist

Art tells you things you dont know you need to know until you know them.

Peter Schjeldahl, art critic

N EW YORK. On Monday, November 8, 2010, at 6:43 pm, at the brand new auction headquarters of Phillips de Pury at 450 Park Avenue, auctioneer Simon de Pury hammered down lot 12. This was a lifelike, nude waxwork of former actress and supermodel Stephanie Seymour. Designed to be mounted on the wall like a deers head, it is titled Stephanie but known in the art world as Trophy Wife. The sculpture turns the representation of Seymour into a literal trophy, her nude upper body arching from the wall, breasts covered not very discreetly with her hands (illustrated in center section).

The sculpture, one of four identical versions conceived by Italian artist Maurizio Cattelan, was expected to bring between $1.5 and $2.5 million. De Pury predicted it might go as high as $4 million. After nine bids from six bidderstwo of those bidding on the telephoneit sold in 40 seconds for $2.4 million, including buyers premium (the additional amount charged by the auction house, above the hammer price). The successful bidder was New York ber collector and private dealer Jose Mugrabi.

T he very highest levels of the contemporary art world are brand- and event-driven. But over the history of marketing contemporary art, the fall 2010 Phillips auction stands out for its mix of brand, event, celebrity, back story, and astonishing prices. The presentation of Stephanie, and the logic behind the auction of which it was a part, is a wonderful example of marketing high-end contemporary art.

Phillips de Pury is a medium-size art auctioneer operating primarily in New York and London. In celebrity quotient and prestige, Phillips runs a distant third to Christies and Sothebys, with about a tenth the annual dollar turnover of either. Those two auction houses sell almost 90 percent of all contemporary art over $2 million. Phillips wanted a greater share of this high value, much more profitable segment. The cost of gaining the consignment and promoting a $2 million work may be twice that of a $200,000 work, but the profit after expenses is five to ten times as large. Those consigning at an exalted price level generally prefer to do business with Christies and Sothebys, the assumption being that these houses will produce higher bids.

After a mediocre 2010 New York spring sale in which only one work sold at over $1 million, Phillipss strategic problem was how to create buzz for their fall contemporary art auction. Their expensively renovated new auction room on Park Avenue provided the setting.

Simon de Pury, as chairman and also chief auctioneer of Phillips, created what he called a Carte Blanche auction. He asked Philippe Sgalot to act as guest curator, just as a museum might invite an outsider to curate an exhibition. Sgalot was at one time the international head of contemporary art at Christies, where he pioneered theme partiesone called Bubble Bash, another Think Pinkto attract younger buyers to the auction house. Later he became co-owner of the art advisory Giraud Pissarro Sgalot. Sgalots major client is Franois Pinault, the French billionaire who controls the luxury brands Gucci, Balenciaga, and Stella McCartneyand also owns Christies auction house. Pinault has a $2 billion collection of art by Jeff Koons, Damien Hirst, Cindy Sherman, and Richard Serra, and older works by Picasso, Braque, and Mondrian.

Sgalot was given freedom to choose the art for the Phillips auction and stage the sale of his dreams, with no interference from de Pury; he described it as a self-portrait of my own taste. He assembled 33 works, with a total value estimated between $80 and $110 million (all figures US dollars). None of the 33 came from Phillipss regular auction consignors. Three came directly from artists and some from Sgalots own collection. A few were owned by his private clients, as reported in The Economist : two from Pinault, one of which was Stephanie. The idea that the owner of Christies would consign work to another auction house raised eyebrows.

A half dozen of the works were chosen for their newsworthiness. This usually means a branded artist or controversial subject. With Stephanie, it meant both. Stephanie was not the most expensive work, but it was the one featured in advertisements and on the cover of the auction catalog.

Phillips was founded in London by Harry Phillips in 1796. Bernard Arnault and his luxury goods firm LVMH acquired the firm in 1999 for a reported $120 million. A year later Arnault brought in art dealers Simon de Pury and Daniella Luxembourg to run the company and to challenge the dominant pairing of Christies and Sothebys. LVMHs strategy floundered among overly generous guarantees (that a targeted auction price would be achieved) given to consignors to attract auction lots. Arnault sold control to de Pury and Luxembourg in two tranches in 2002 and 2004. Luxembourg sold her share to de Pury in 2004. In 2008 de Pury sold a controlling share to Russian luxury goods group Mercury for $80 million, half of which reportedly went to paying down Phillipss bank overdraft. Two weeks after the Mercury purchase, the auction house bottomed-out, with a contemporary evening sale in London in which just 25 percent of the lots sold.

Simon de Pury generated more media attention than the auction house. For months before the auction he was familiar to television viewers as mentor and critic to aspiring artists in Bravos World of Art, a choose Americas next great artist TV reality show in which one artist was bounced each week until a winner (Abdi Farah) remained.

Next page