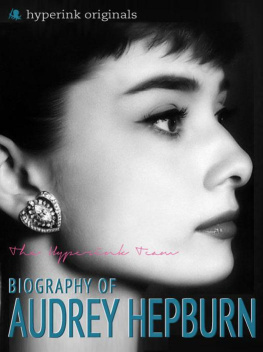

Audrey riding a tiger, c. 1915.

Audrey in a scene from Purity (1916).

When Audrey Munson was a girl of five, the Gypsy Queen Eliza came to the United States from England. Eliza Cooper was just eighteen but had reigned over 55,000 Roma since succeeding to the throne at the age of ten. Touring the country by train, Queen Eliza stopped in upstate New York to be hosted by Plato Bucklands thirty-five-strong Gypsy band in East Syracuse. A colorfully painted wagon carried her from the railroad station to the camp on Eastwood Heights, and she was installed with her maidservant in a white tent filled with bright new rugs. In place of a crown, she wore an intricate lace cap on her head.

Bands of gypsies passed through East Syracuse each summer, before their caravans headed south for the winter. They set up their tents on the heights outside the village or near the railroad freight yards. The Gypsy men, though renowned for thieving, earned an honest living from horse-trading and tied up their horses all around. The women sold basketwork and lace and read palms.

Queen Elizas presence provoked intense curiosity. Thousands of nearby residents turned up to catch a glimpse of Gypsy royalty. Many, believing superstitiously in the prophetic powers of the Romany women, crossed their palms with silver to have their fortunes told.

Audrey was taken to the Gypsy camp in East Syracuse by her mother as a child, possibly amid the excitement of the royal visit. She did not see the Gypsy queen. Queen Eliza stayed only thirty-six hours. Audrey was fascinated instead by the games the Gypsy children played amid the covered wagons. The tall, fierce men frightened her. But her mother insisted Audrey have her future read, and led her by the hand into the tent of a bronze-faced seeress.

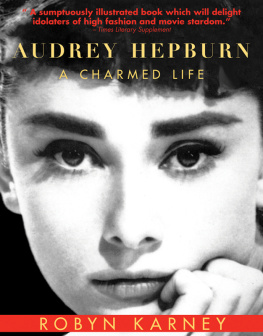

Though still just a slip of a girl, Audrey was already possessed of a limber figure and long bonesshe was to grow to 5'8" tall. Her features were perfectly symmetrical and sleek: a high brow, chiseled cheekbones, an almond jaw, and that perfectly straight neoclassical nose. Set like gemstones in her milky skin, she had questioning, slightly impertinent gray-blue eyes. The question lurking in those eyes was one she would come to wish she had never asked: What does my future hold?

The soothsayer looked on Audreys fresh beauty; then, mindful of her own sorrows and all the sorrows of the world, she spoke:

You shall be beloved and famous. But when you think that happiness is yours, its Dead Sea fruit shall turn to ashes in your mouth.

You, who shall throw away thousands of dollars as a caprice, shall want for a penny. You, who shall mock at love, shall seek love without finding.

Seven men shall love you. Seven times you shall be led by the man who loves you to the steps of the altar, but never shall you wed.

For the rest of her life, Audrey considered the prophecy a curse.

Audrey did indeed become beloved and famous. Her most perfect form still reigns over New York City and across the United States. You probably already know her, without even knowing you know her. You may have passed her on the street many times, unbeknownst. For she was Americas first supermodel. She is the second-largest female figure in New York after the Statue of Liberty. Her gilded form stands twenty-five feet tall, holding a crown aloft as the symbol of the city, atop the vast Municipal Building across the street from City Hall. She frolics in the Pulitzer Fountain outside the Plaza Hotel at the southeast entrance to Central Park, her celebrated dimples on full display to the shoppers at the Apple Store. Every day, office workers tramp past her as the centerpiece of the Maine Monument in Columbus Circle at the opposite corner of Central Park. She stands on the arch at the end of the Manhattan Bridge as the Spirit of Commerce, waving on commuters to their toil. She once also stood sentry at the Brooklyn entrance of the Manhattan Bridge as Miss Manhattan and Miss Brooklyn. But those colossal forms now flank the entrance to the Brooklyn Museum. Audrey is immortalized in stone at the New York Public Library and on the Frick House on Fifth Avenue. She is the reclining bronze figure of Memory on the Straus Memorial on the Upper West Side. She is the two grieving stone figures on the Firemens Memorial on Riverside Drive. Wherever you go in New York City, Audrey is looking at you.

Across the nation, from Florida to California, Audrey remains in our everyday lives. She stands as Liberty and Sapienta (Wisdom) on the Wisconsin State Capitol. She can be seen as the nymphs on the James McMillan Memorial Fountain by the reservoir in Washington, DC. She was the model for Allen George Newmans Monument to Women of the Confederacy in Jacksonville, Florida, and for his Peace Monument in Piedmont Park, in Atlanta, Georgia. She posed for the figure of Evangeline inscribed on the Henry Wadsworth Longfellow Memorial in the garden of the poets house by the Charles River in Cambridge, Massachusetts. She inspired three-quarters of the statuary of the Jewel City built in San Francisco for the 1915 Worlds Fair. A famous bronze of one of those statues, Descending Night , was acquired by press baron William Randolph Hearst, and now resides at Hearst Castle in San Simeon, on the California coast. One of her surviving Star Maidens from the fair now stands in the courtyard of the Citigroup Center building in San Francisco.

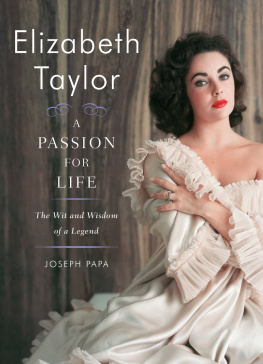

It is even still possible to see Audrey in motion. She was the first movie star to go naked in an American film. Inspiration (1915) has been lost, but we can yet marvel at her in Purity (1916). Playing the scantily clad allegorical character Virtue, her breasts popping out of her robes at every opportunity, Audrey was quite literally a sex goddess.

Audrey posed for Allen George Newmans Monument to Women of the Confederacy in Jacksonville, Florida, one of her many statues still with us today.

This book is a biography of a naked woman, once the most famous nude in America. Of course, every woman is a naked woman, every man a naked man. Audrey herself once said: If there is immorality in posing in the nude, anybody who takes a bath ought to be arrested. But Audrey was known above all, in art and in movies, for her naked bodyand her daring readiness to put it on show. She was advertised as the worlds most perfectly formed woman. Audreys defense of her public nudity, and somebut certainly not allof her other views on women, made her an early feminist. Indeed, she once contributed five dollars to the suffrage movement pushing to get women the right to vote, which was finally achieved in her heyday, with the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920.