Table of Contents

Come slowly, Eden!

Lips unused to thee,

Bashful, sip thy jasmines,

As the fainting bee,

Reaching late his flower,

Round her chamber hums,

Counts his nectarsenters,

And is lost in balms!

EMILY DICKINSON

For Brian

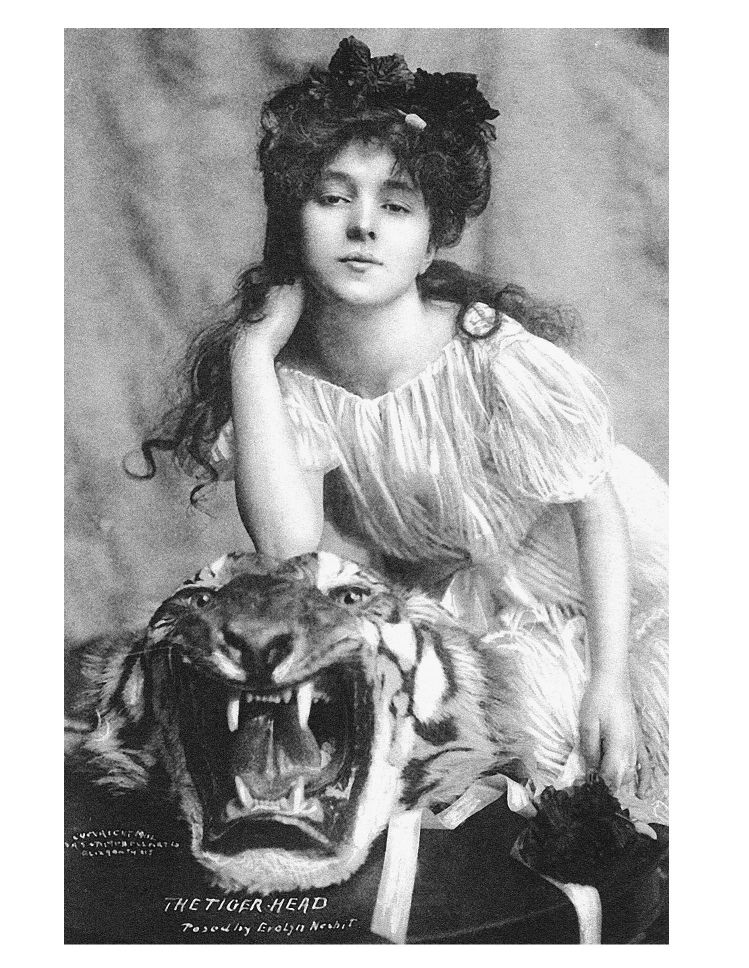

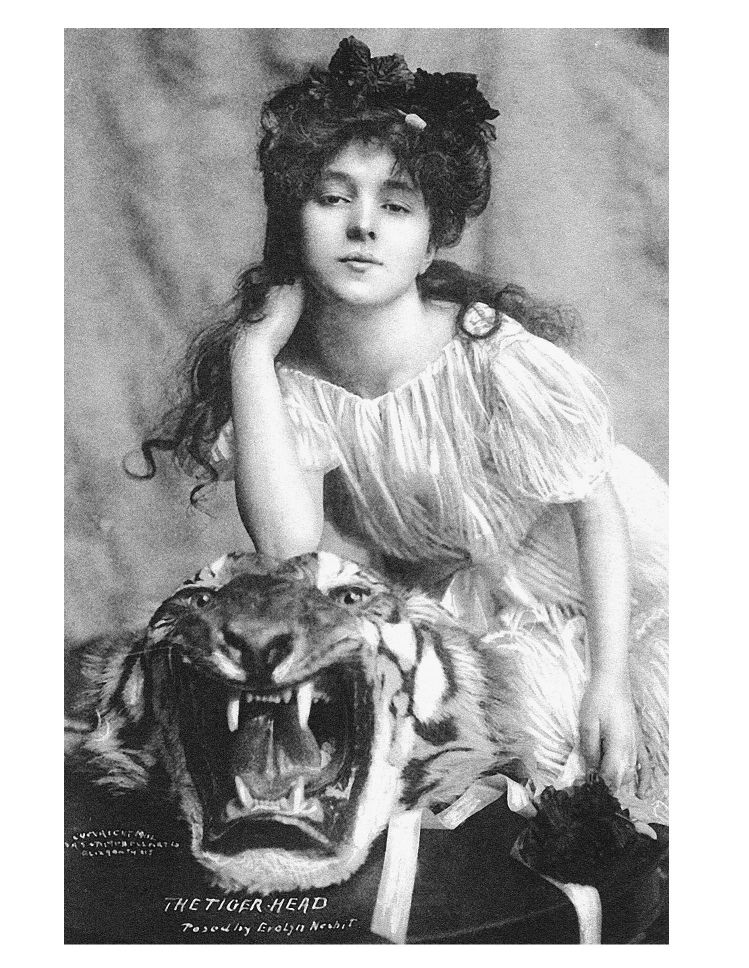

Campbell Art Studio postcard photo

of Evelyn, 1901, The Tiger Head.

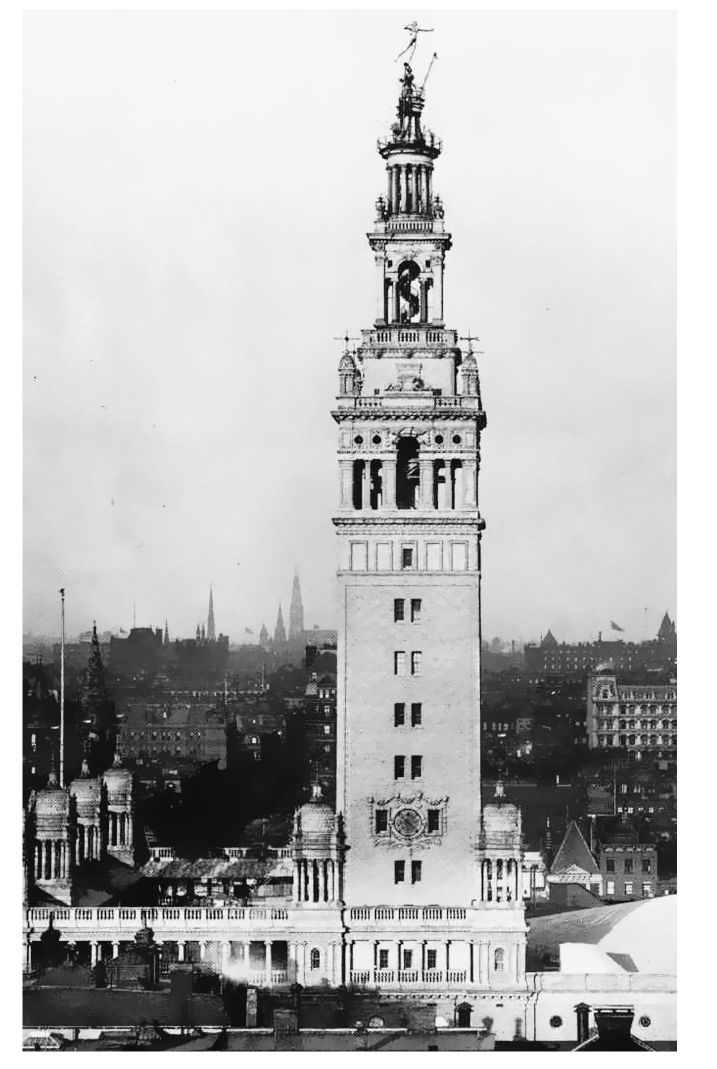

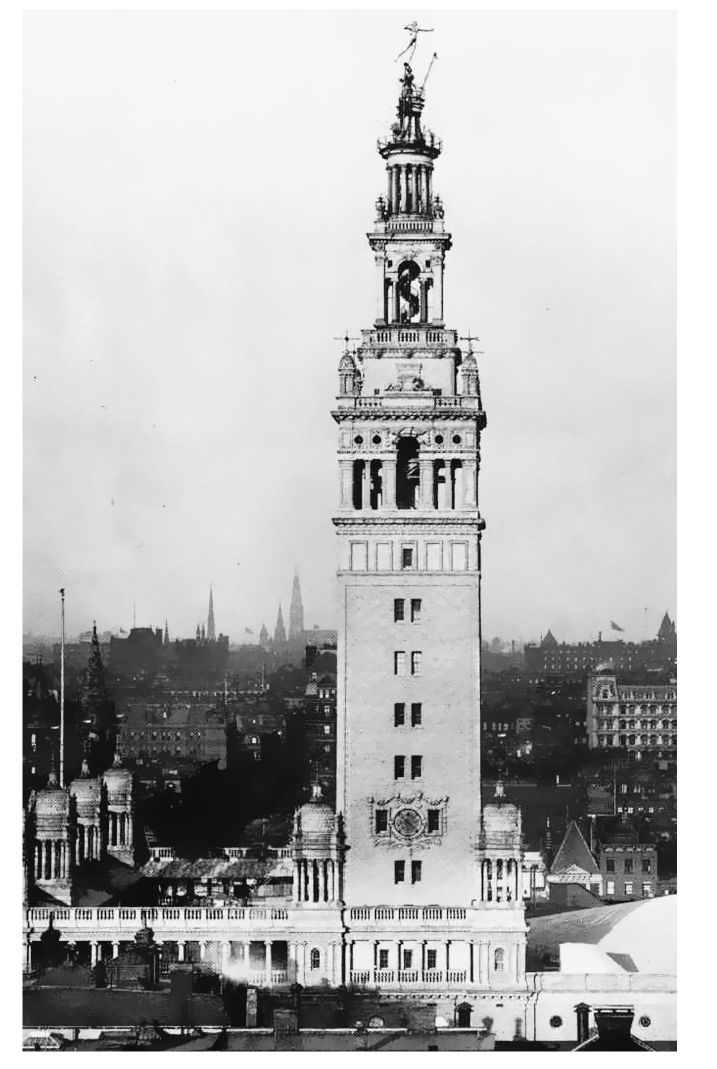

Diana atop the Madison Square Tower, circa 1900.

INTRODUCTION

The Garden of the New World

For we must consider that we shall be as a city upon a hill, the eyes of all people are upon us.

John Winthrop, sermon, 1630

God gave me my money.... God has marked the American people as His chosen nation to finally lead in the regeneration of the world. This is the divine mission of America and all it holds for all the profit, all the glory, all the happiness possible to man.

John D. Rockefeller, 1900

Rockefeller did the things that God would have done had He been rich.

Anonymous

Nature is very cruel... and if civilization has overlaid us with delicacies and refinements, nature works on just as though social laws had no existence.

Evelyn Nesbit, Prodigal Days

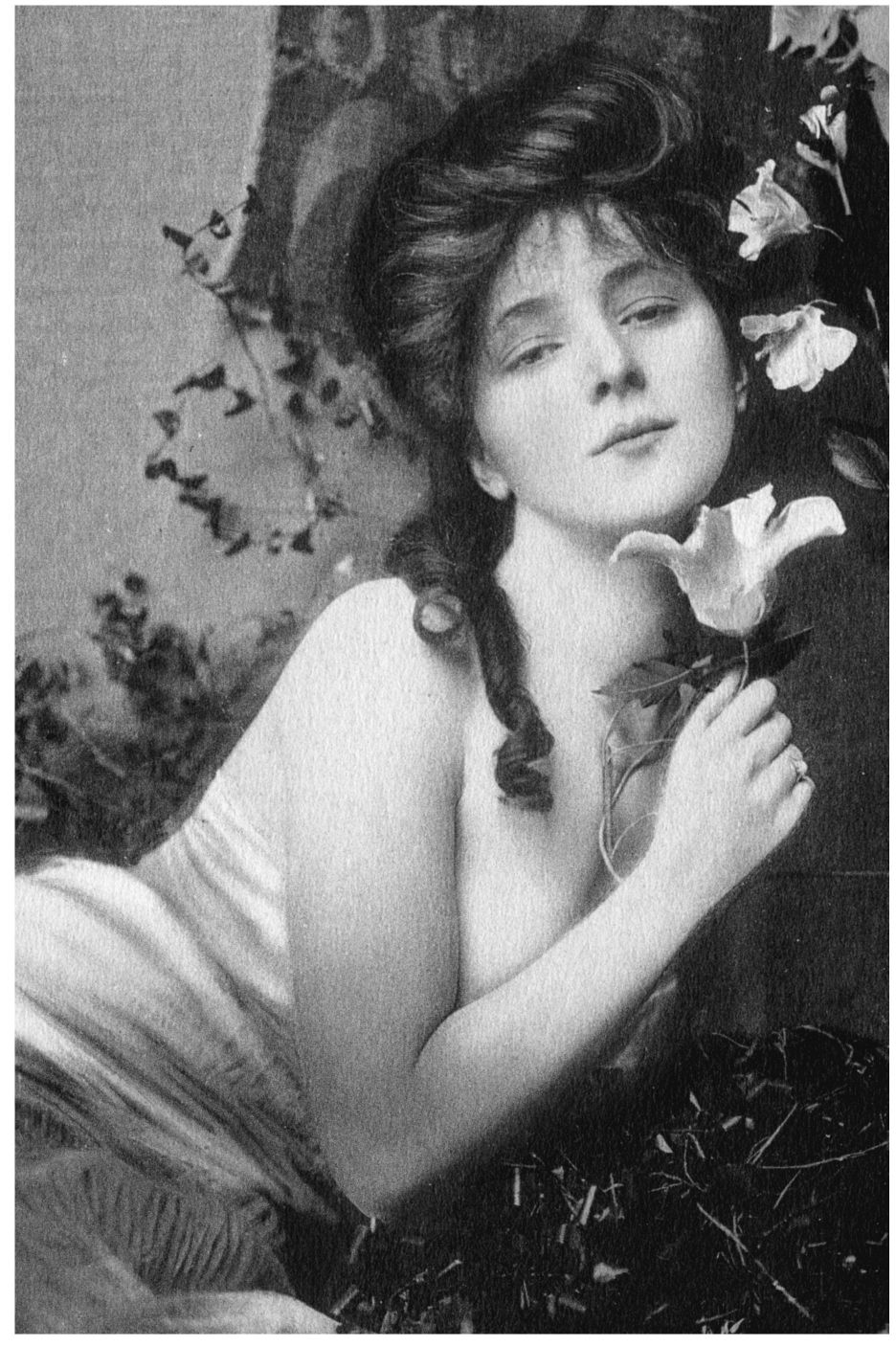

Little more than half a century before a winsome, waiflike, and wide-eyed Evelyn Nesbit, not yet sixteen, found her way to the island of Manhattan, Nathaniel Hawthorne had written a modest allegorical tale titled Rappaccinis Daughter. It is the story of an intense but immature medical student who becomes obsessed with an exquisitely lovely and innocent young woman. The girl has never ventured beyond the walls of her outlaw scientist fathers garden, a man-made paradise filled with marvelous-looking but unnatural species of fatally toxic plants and flowers. The illicit garden is the envy of a less than brilliant rival scientist, intent upon finding his way into the forbidden sanctuary and learning the secrets of his seemingly untouchable rival. Upon seeing the splendid flora and the rare beauty of the girl, the young man wonders, Is this the Garden of the New World? only to find out subsequently that the girl and everything in the garden are poisonous as a result of her fathers unsanctioned experiments. When he realizes he has become contaminated with the poison through exposure to the beautiful girl, the young man viciously turns on her and blames her for his condition. The girl, betrayed and brokenhearted, decides to sacrifice her life for him by releasing the poisons in her system via a lethal antidote. She dies slowly and painfully at their feet as the medical student, her father, and her fathers rival look on, respectively horrified, mystified, and triumphant.

The island of Manhattan at the turn of the last century was uncannily like Hawthornes fictional New World Eden. It was a walled-in, man-made wonder, filled with dazzling but lethal temptations, bitter rivalries, and dangerous secrets. It was run by a handful of powerful men, a number of whom acted with impunity outside the boundaries of conventional practices in their ruthless pursuit of both profits and pleasure. In what would prove to be a decade of overindulgence that would nearly devour itself and sink with titanic hubris only a few years later, the chosen class of calculating Calvinists who sat at the top of the food chain ruled over their classless empires of excess, believing they were blessed with divine right. Having reduced their methods of acquisition to an exact science, they amassed astonishing tax-free fortunes, lived in magnificent mansions, rode in fabulous private Pullman cars on the railroads they built and monopolized, and sailed on luxurious yachts that were themselves floating palaces. When asked about his yacht, the Corsair, J. P. Morgan replied famously, If you have to ask how much it cost, you cant afford it. It was social Darwinism at its bestor worst.

By February 1900, New Yorks John D. Rockefeller, the president of Standard Oil, asserted, The growth of a large business is merely survival of the fittest, a law of Nature, and of God. Then he crushed all his competitors into blackened viscous muck. Within a year, months before Christmas, Pittsburghs Andrew Carnegie gave himself an early present. He sold his interest in Carnegie Steel to New Yorks J. P. Morgan for a whopping $480 million. So, while the average working stiffs salary was slightly less than five hundred dollars a year, as the story goes, Carnegie retired on a pension of $44,000a day.

Yet with the exception of a fistful of trust-busting politicians, certain resolute muckrakers, and the occasional enterprising anarchist, the huddled masses seemed unable to comprehend and unwilling to consider the colossal inequality between themselves and Americas staggeringly wealthy untaxed multimillionaires, men like E. H. Harriman, Russell Sage (who, it was rumored, was so cheap he didnt wear underwear), and Henry Clay Frick, who proclaimed that railroads are the Rembrandts of investment. (The latter two even managed to survive violent attacks by anarchy-minded assassins.) These fittest Philistines bought paintings like other people bought penny postcards, and even if the Vanderbilts, Whitneys, Goulds, and their socially well-bred peers did not always know good art, they knew what they liked to buy. If they didnt, they called upon Stanford White to decide for them.

The self-ordained purveyor and pillager of high art for Americas highest society (whose approach to art was usually either a disheartening middle-brow indifference or a more positively demoralizing vanity), Stanford White was the most conspicuous partner of the preeminent architectural firm of the day, McKim, Mead, and White. Like White himself, the firm grandly embraced both the public and the private. Their jewels included the Admiral Farragut Memorial; the Tiffany, Whitney, Pulitzer, and Vanderbilt mansions; St. Pauls Church; Judson Memorial Church; the New York Herald Building; the girded wrought-iron wonder of Pennsylvania Station; and the marvelous Washington Square Arch, now New York Citys most elaborate tombstone (being located near what was a potters field for the indigent and then a burial ground for yellow fever victims, totaling somewhere in the neighborhood of 20,000).

ber-society impresario, aesthetic prophet, protean clubman, and all-consuming libertine, White was the creator of Manhattans own Garden of the New World. Morgan and Carnegie were two of its major share-holders (along with White himself). A block-long business and entertainment complex located at the northeast corner of Madison Avenue and Twenty-sixth Street, the Garden was an oasis of splendor situated adjacent to the formerly unassuming Madison Square. (The present-day Madison Square Garden arena, still colloquially called the Garden, is actually in its fourth incarnation, located between Thirty-first and Thirty-third streets and situated on top of the second Pennsylvania Station.)