Two nurses stood chatting outside Edith Masons door, sneaking glances of their new charge. She lay in bed, smoking, her eyes red welts below a mass of tangled, badly-dyed hair.

Poor thing, whispered a smartly-bobbed blonde. I heard they needed a straitjacket for her.

The brunette shook her head. Nah, just handcuffs. She glanced at down at her chart. Dr. Geiger says here she was real tight though, kicking and biting and screaming like she was crazy.

The bobbed blonde stole a look. Edith Mason. You know I heard thats not even her real name? My friend saw her check into the Palace. Said shes Corliss Palmer.

Corliss Palmer, the movie star. Remember her? She was always in the papers after she won that beauty contest

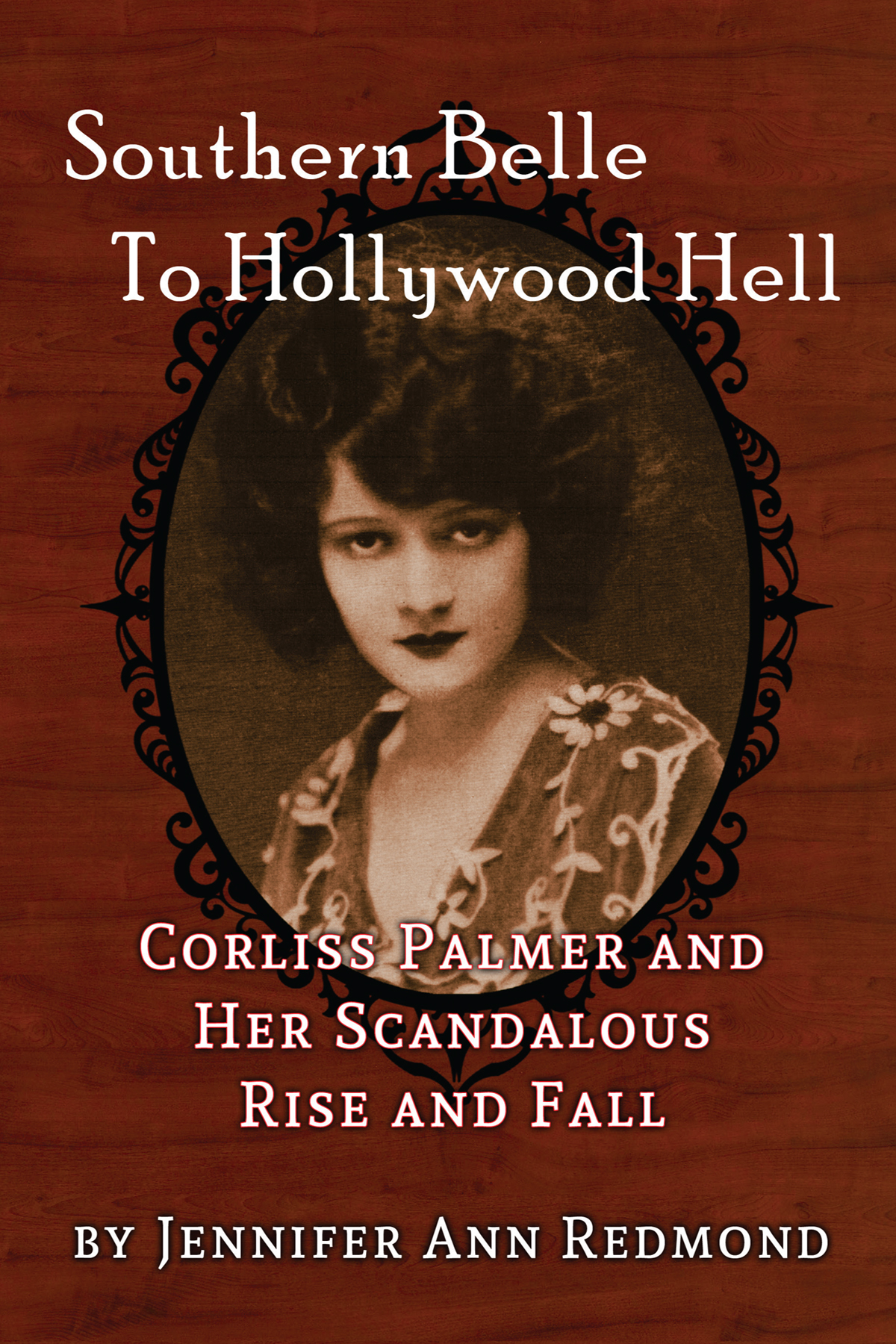

Thirteen years ago. Lucky thirteen. Corliss was a pretty Georgia girl then, with thick auburn hair and a cherubs face. Now her cheeks were wan, her forehead creased by worry and sorrow. I want to die, she wept. I have nothing to live fortoo many promises made to me have been broken.

Every girl is born a princess, blessed by the fairies with beauty, health, joy, charmat the same time, the evil fairy also was present with her curse.

Corliss Palmer, In League with the Fairies

There are few things as boring as a cigar stand during the off time. At least there was no shortage of reading material, Corliss thought, thumbing aimlessly through yet another magazine. This one was Motion Picture, one of her favorites. She devoured the love stories adapted from the latest flickers, which drove Mama crazy. Your mind is gonna grow weeds! Towards the back of the issue, something caught her eye: an ad proclaiming the Fame and Fortune Contest for 1920.

Fame and fortune. Could you imagine? she murmured, envisioning herself swathed in furs and diamonds, laughing over lobster with Norma Talmadge or Richard Barthelmess. She already knew she was pretty. People said shed gotten her job at the general store more for her face than for her skills, and she had no shortage of smiling businessmen buying way too many packets of Sen-Sen from her counter here in the Hotel Dempsey.

Hey, Daisy, she called to a tall girl stacking boxes. Have you seen this?

Daisy wiped her hands on the front of her dress and ambled over. She pulled the magazine closer. Yup! Me and some of the others are gonna send our photos in. Hey, do it with us! Itll be a scream!

Corliss laughed. Maybe I will. I have a photo at home I can send. Its not much, but itll do. She dogeared the page and slipped the magazine under the counter. Mary Pickford, move over!

That night in bed, the envelope waiting on her dresser for the morning mail, Corliss dreamed with her eyes open. She mused on how her life could changeand how much it already had in the last few years. Before, the Palmers lived a simple but happy life by all appearances. Luther, Julia, and their six children rented a modest South Court Street house in Quitman, Georgia, right near the Florida line. Luther was a machinist in the electric plant, and Julia kept house and kept Mary, Corliss, Hoke, Ennis, Grady, and Stanton from climbing the walls most days. Corliss in particular was a challenge, perpetually in motion like her namesake engines at the plant. It was a big, messy, noisy household, and they rejoiced the day Luther was promoted to supervisor.

One Sunday morning in June Luther felt odd. When a shot of his usual rye failed to perk him up, he decided on a bath. Police found him passed out on the bathroom floor; hed never even filled the tub. Despite the utmost efforts of his physicians, he never regained consciousness, and died at 3:30 am Monday, June 20, 1910. They never did find out what killed him at the young age of 38.

Julia was left grief-stricken and terrified. How was she going to support six children under the age of 14 with zero income? Thanks to Luthers estate they had a little money, but it wouldnt last long. Luther was a Mason, and in good standing, so she sent the kids to the Masonic Home until she found a new revenue stream, in the way most women did then: she remarried. The whole family (save Stanton, who remained at the Home) moved to the home of Julias new husband in Macon. James Simmones job as foreman of Allied Packers provided much-needed financial security, and he and Julia had three children together: Katherine, James Jr., and Julia Jr.

Corliss and her siblings were shaped by their mothers upbringing in the small Providence neighborhood of Jemison, Alabama. Chilton County, bordered by the Coosa River, was only ten years old when Julia Farrell was born in 1877. Rural and primarily agricultural, its plentiful pines fed a thriving lumber industry; the sawmill erected in 1872 employed much of the region, including Julias father John.

Life in the Reconstructionist South was confusing and filled with upheaval. Affluent old-guard whites, secure at the top of the food chain, fought Black progress overtly through hate groups like the KKK and covertly through political disenfranchisement and segregation. Many saw Jim Crow laws as necessary for peace. For the poor and working class, who needed as many family members earning an income as possible, education was dismissed as unnecessary and untrustworthy. In 1880 over half of Alabama was illiterate, and those who attended school did so only three or four months out of the year, up to sixth grade. Christine Lindquist, in remembering her grandmother, noted her lack of education Julia never attended a single day of school and her distrust of people of color. As the only constant in their lives, its only natural that fervency against poverty and abhorrence of those seen beneath them seeped through to the children.