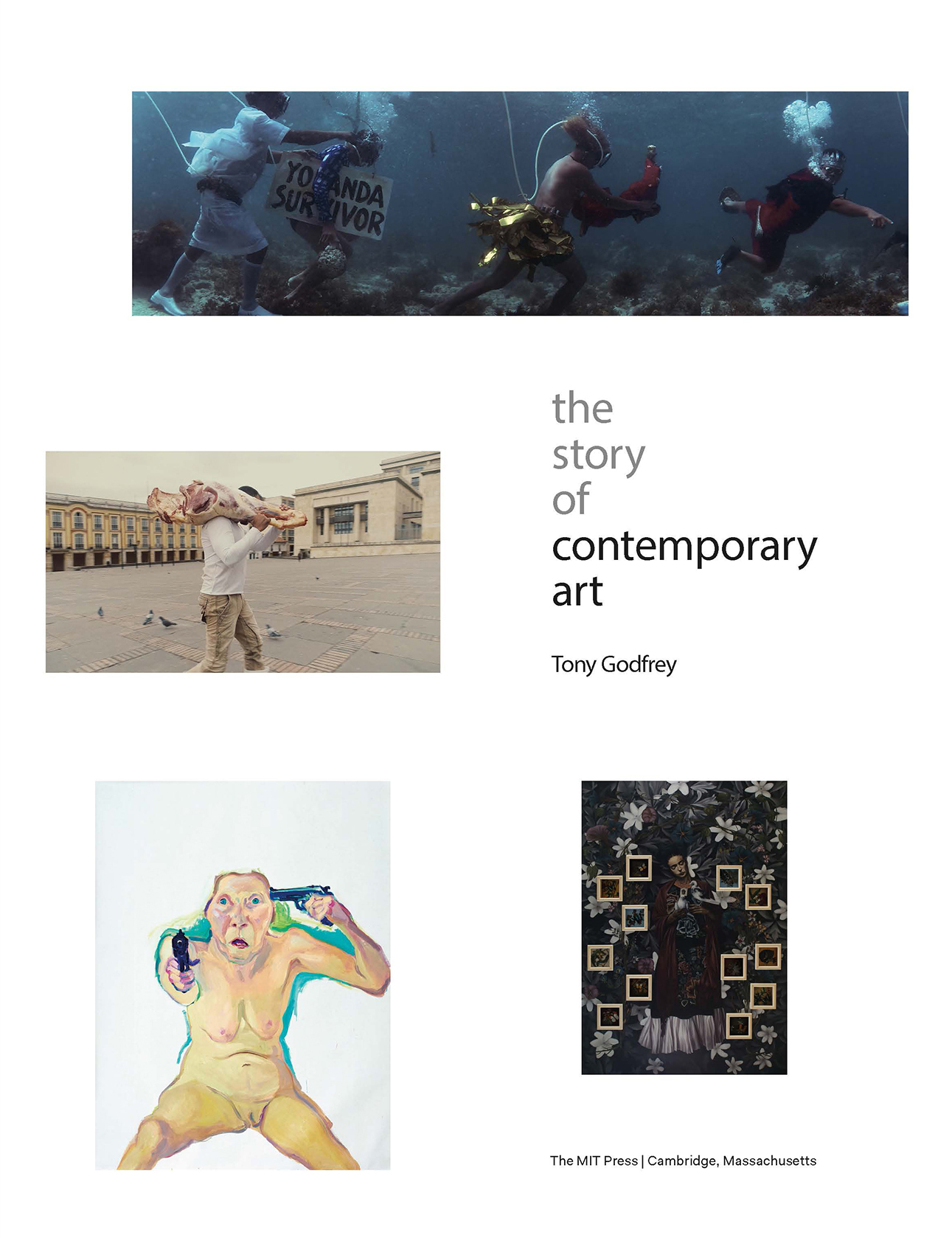

About the Author

Tony Godfrey, former Programme Director of the MA in Contemporary Art at Sothebys Institute, London, now lives in Manila, where he works as a curator with artists from South-East Asia. He has written for the Burlington Magazine and Art in America, and is the author of Conceptual Art and Painting Today, as well as numerous exhibition catalogues.

Contents

People are intrigued but often puzzled by contemporary art. I have spent the last forty years of my life trying to explain it and, even more importantly, trying to get people to enjoy and think about it. Often, someone will ask me to recommend a book to act as an introduction to this curious subject. But although there are many books on contemporary art, it is hard to think of one that I would recommend without reservation: they are either too partial or partisan, written in the dense language more suited to a PhD thesis than the general reader, or else too much like a mail-order catalogue, gushy and uncritical.

Some months ago, I picked up for the first time in many years a copy of Ernst Gombrichs The Story of Art, and was struck by how clear and readable it is. No wonder it is said to be the best-selling art book of all time! Could one, I wondered, tell the story of contemporary art with similar clarity and readability? Gombrich wrote in the preface to his book that it was intended for all who feel in need of some first orientation in a strange and fascinating field In writing it I thought first and foremost of readers in their teens who have just discovered the world of art for themselves I have striven to avoid these pitfalls [pretentious jargon and bogus sentiment] and to use plain language even at the risk of sounding casual or unprofessional I would not write about works I could not show in the illustrations; I did not want the text to degenerate into a list of names. Could one write such a book on contemporary art, I asked myself? Why not?

Contemporary art, despite its name, is not just art made now. Rather, it is a certain type (or types) of art, as well as the attitudes towards it. So, it must have a story. But when does that story begin? In 1945, 1960, 1968, 1973, 1980, 1989, 2001? You can make an argument for any of these dates. For me, however, as we shall see, 1980 was the decisive moment when how art was made, shown and collected seemed to change.

If contemporary art is a story, then what is the storyline? What are the plots and subplots? Who are the main characters the heroes, heroines and villains? Which artists best typify the millions of other artists working today?

Significantly, I dont think there can be such a clear narrative of progress as there would seem to be in Gombrichs book. Instead, the story of contemporary art must be told as a series of often turbulent crises, conflicts and arguments about what art (and society) is or should be, with many of these arguments remaining unresolved and potent to this day: the exhaustion of modernist art, painting versus conceptual art, appropriation versus neo-expressionism, the national versus the global, etc. One of the things that makes contemporary art so exciting is that it is often about the pressing issues of our day: identity, environmental disaster and virtual life. As we look at individual artists, we might forget about that overall story, but we will keep coming back to it.

And who, you may ask, am I, your narrator? Well, I was born and raised in England, and began to teach and write about art in the late 1970s. I lived in London but travelled often around Europe, the United States and Mexico. In 2009, I went to live and work in South East Asia. That made me see the world of contemporary art very differently.

But before we move to the 1980s and the beginnings of contemporary art, we must first of all think broadly about what contemporary art is, and, secondly, about what was happening in the art world prior to that decade. It is also important to remember that a book about the art of our time can only ever be personal. Sometimes you might disagree with my opinion, but thats great! It means we are having a discussion. And contemporary art is all about discussion.

T. G., November 2019

What does that mean? Is that really art? Why does that cost so much money? These are some of the questions I am often asked about contemporary art. They are not the questions that E. H. Gombrich felt compelled to answer in 1950, in his famous book The Story of Art. The questions he sought to tackle were very different: What is beauty in art? Should art be true to nature? What is harmony? To illustrate his answers to such questions, Gombrich called on Raphael, Drer, Rembrandt and other great masters of European painting.

Contemporary art seems often to be utterly different from what went before. Indeed, Gombrich felt unable to integrate it into his larger story: even in 1994, when he made what would be his final revisions to the book, the only contemporary artworks he condescended to illustrate were a painting by Lucian Freud and a photographic work by David Hockney figurative pieces that such nineteenth-century artists as Manet or Degas would have had no difficulty comprehending. Gombrich included nothing that showed the impact of Pop, minimalist or conceptual art, those movements of the 1960s that initiated what we still call contemporary art.

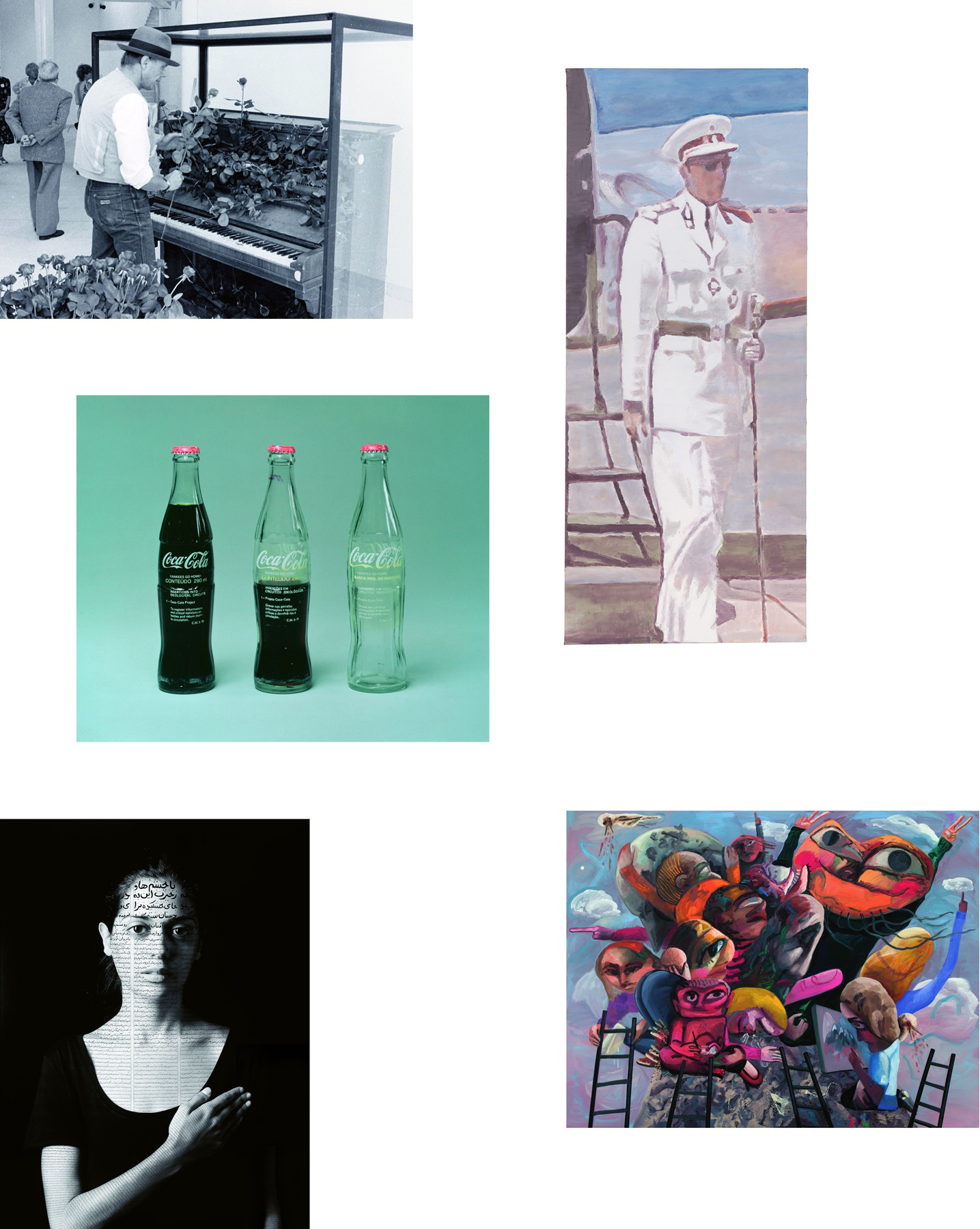

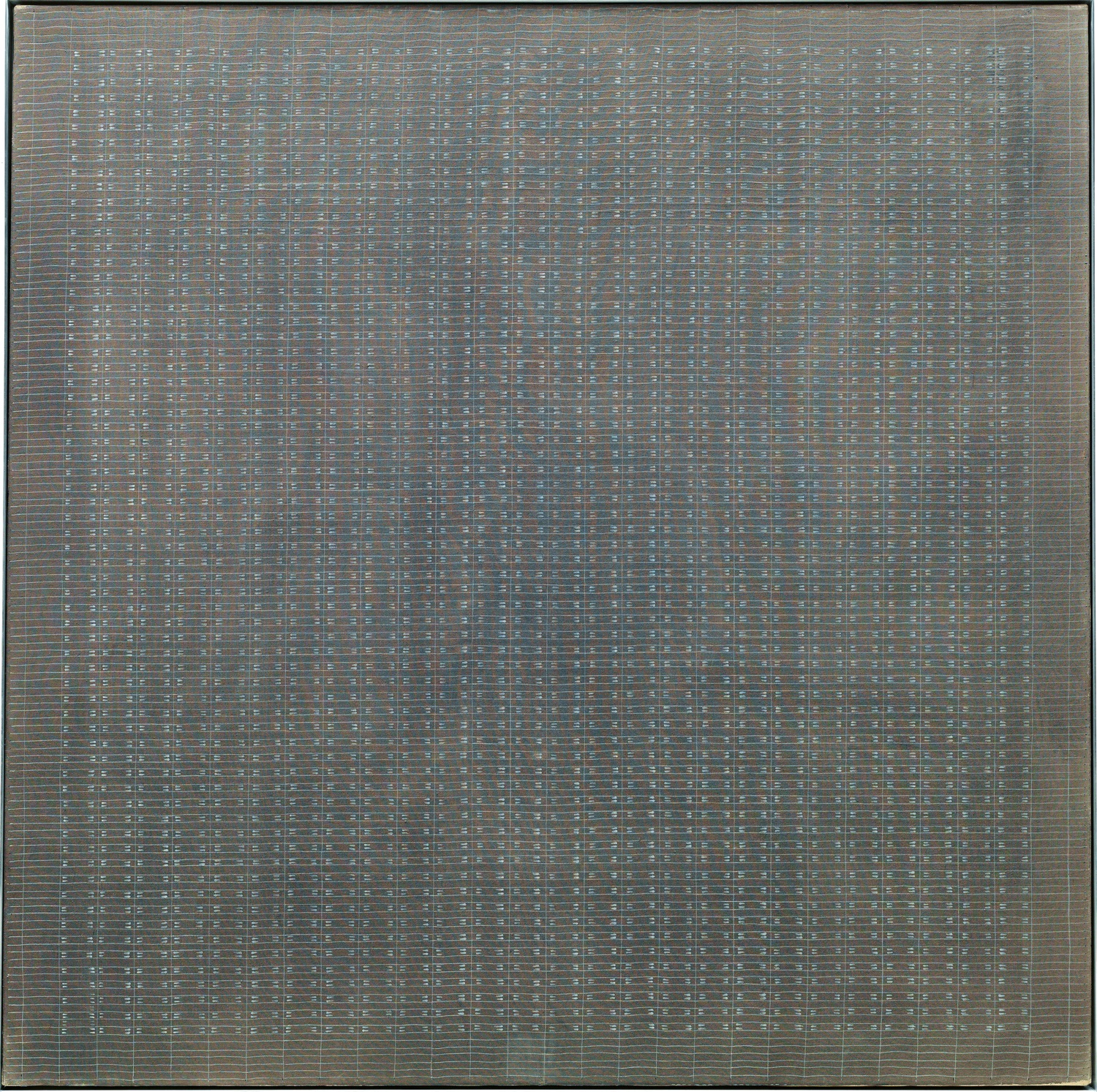

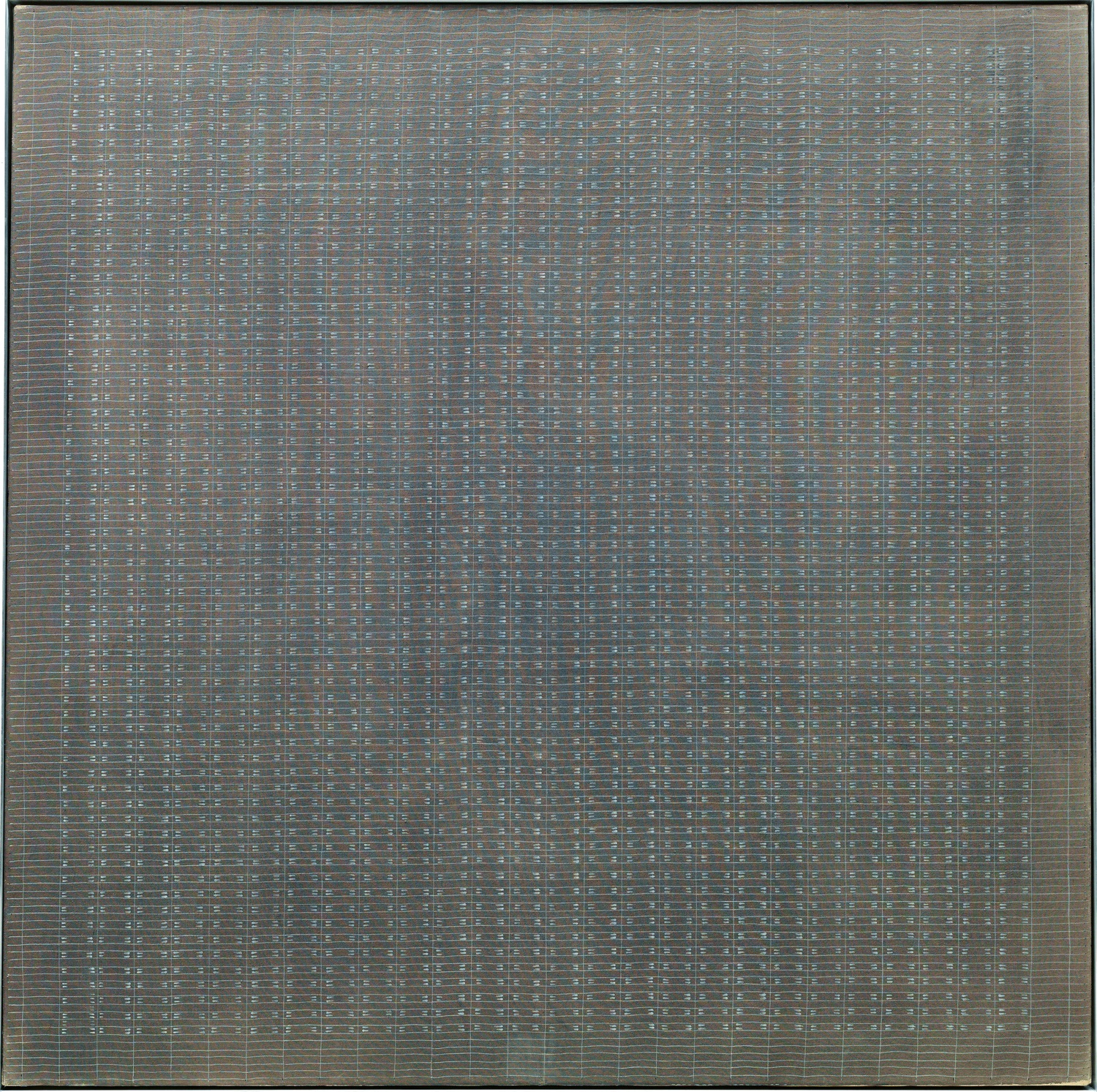

Without doubt, Gombrich would have had no sympathy for either White Flower (), by Agnes Martin and John Baldessari respectively. Where, he may have asked, is the skill in such work? All the former has done is draw rows of straight lines, while the latter has simply scribbled some words under a pair of photos. But the very point of Baldessaris piece is that it shows no manual dexterity: we can all write, take snapshots like these and sharpen our pencils. What defines the work as art is not the medium, which for Gombrich would have meant exclusively drawing, painting or sculpture, but the way it questions what art actually is. At a certain point in the 1960s, several artists like Baldessari stopped making art, that is to say, any traditional form of art, and started to ask, What is art? It was difficult to pose this question, however, by knocking off another drawing, painting or sculpture. Indeed, to show that a chasm had opened up between what he had made before this loss of faith, Baldessari cremated all his old Abstract Expressionist paintings and, as we shall see later, made a new artwork out of this destructive act.

Agnes Martin, White Flower, 1960

Oil on canvas, 182.6 182.9 cm (71 72 in.)

Why should it matter to Baldessari and others what art is? Why should it be so important a question to you? Why should we keep asking this question? I believe its because art can be defined as that which is different, that which is special, as something that is meaningful. We see it this way because of its associations with such terms as genius, individuality, originality, profundity and beauty. We dedicate entire museums to it; people pay vast sums for it; we care for it and strive to preserve it.

Next page