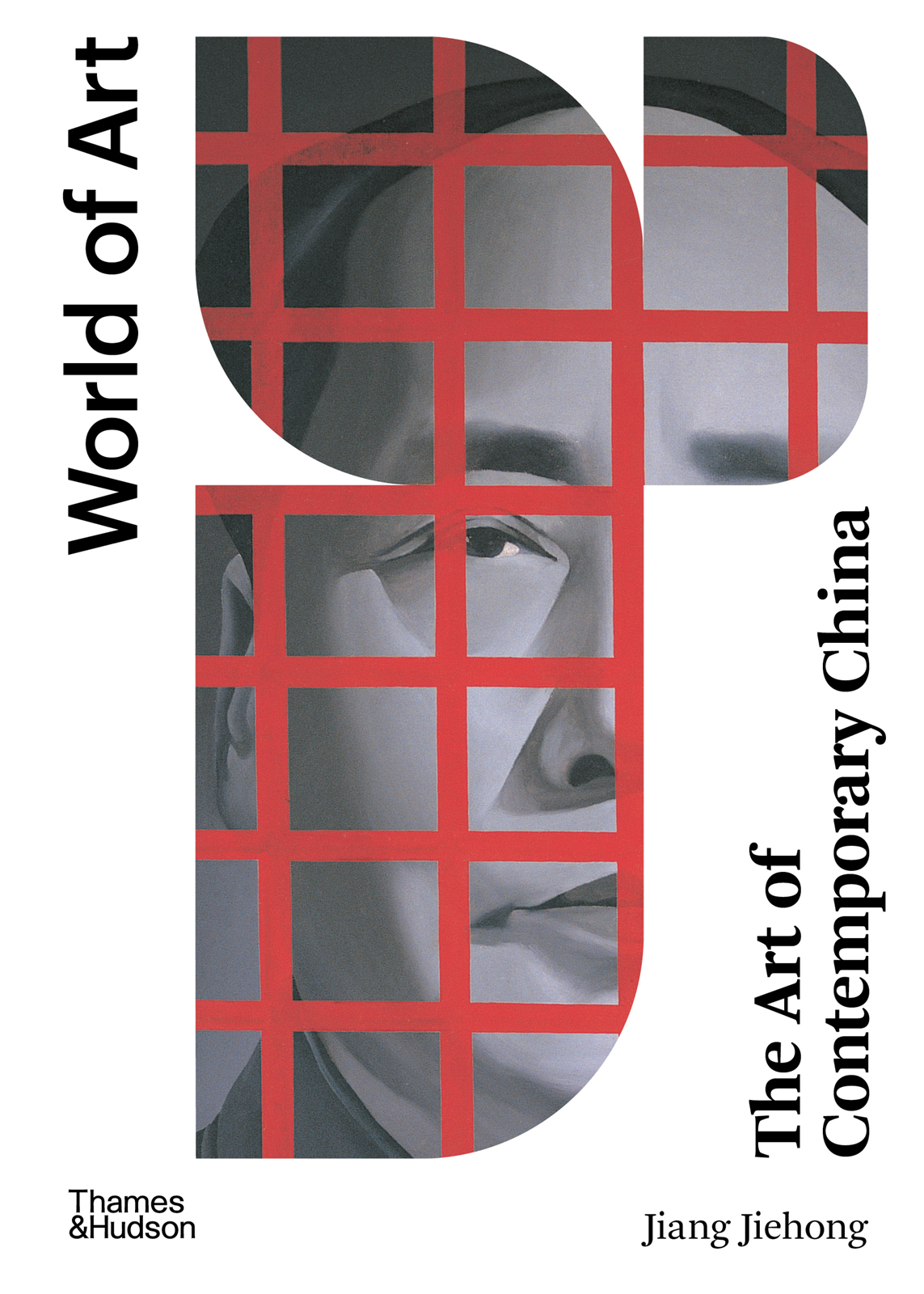

Zhao Zhao, Project Taklamakan, 2016 (detail of performance)

About the Author:

Dr Jiang Jiehong is Professor of Chinese Art and Director of the Centre for Chinese Visual Arts at Birmingham City University, and Principal Editor of the Journal of Contemporary Chinese Art (Intellect). His book publications include Burden or Legacy: From the Chinese Cultural Revolution to Contemporary Art (2007), The Revolution Continues: New Art from China (2008), Red: Chinas Cultural Revolution (2010) and An Era without Memories: Chinese Contemporary Photography on Urban Transformation (2015). Jiang curated the 2012 Guangzhou Triennial, The Unseen; the 2014 Asia Triennial Manchester, Harmonious Society; and the 201819 Thailand Biennale, Edge of the Wonderland.

For Julia and Michelle

Acknowledgments

I owe a great debt of gratitude to all the artists whom I admire and have worked with in the past few years for their inspiration, generosity and hospitality, and for the timely help offered by their family members, studios and gallery assistants.

This project was derived from my ongoing research, curating and writing in the field. I have gratefully received support and assistance from many institutions, including AIVA Shanghai, Asia Art Archive, Beijing Commune, Boers-Li Gallery, CAFA Art Museum, Centre for Chinese Contemporary Art, Guangdong Museum of Art, Ikon Gallery, Leverhulme Trust, New Century Art Foundation, OCAT Shanghai, Open Eye Gallery, Shanghai Minsheng Art Museum, ShanghART Gallery, Tang Contemporary Art, Tate Liverpool and Today Art Museum. At Birmingham City University, I have benefited from the generous support of Research at the Faculty of Arts, Design and Media, and from exchanges with academics and doctoral students at the Centre of Chinese Visual Arts.

This book would not have come into existence without the encouragement and invitation of Constance Kaine and Roger Thorp at Thames & Hudson. I am also indebted to their team, especially Ilona de Nemethy Sanigar, Mohara Gill, Sam Ruston, Poppy David, Luke Kiley, Jenny Wilson, Adam Hay and Isabel Roldan, for their expertise in making this volume possible.

Contents

This book tells a special story of contemporary art in relation to the Peoples Republic of China. It is about art, and it is about China today. The discussions will not unfold in a linear way that charts the development chronologically, as a forty-year history of Chinese art; instead, topics will be generated through a series of curatorial approaches that examine contemporary art in the context of the unprecedented cultural, political and urban transformations in post-Mao China.

The end of the Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution (Wuchan jieji wenhua da geming, 196676) opened an entirely new chapter for modern Chinese history, and indeed for Chinese art too. During the last decade of the twentieth century, Chinese art started to become more visible and to attract the worlds attention via frequent participation in important international art events, such as Documenta and the Venice Biennale. Since the turn of the twenty-first century, the Chinese governments vision of urbanization, a growing national awareness of and anxiety about developing cultural and creative industries within urban spaces, the institution of biennials, triennials and art fairs, the dramatic expansion of art education, and the rise of newly founded private museums and art spaces have all played a part in promoting the development of contemporary art in China.

There are a variety of definitions of new art in China. From a political point of view, on the one hand, such art has been categorized into official and unofficial art, or underground art in the context of a totalitarian society; it has even been coined un-unofficial art, which encourages real freedom of creation in an open, multi-orientational space. In this volume, the term contemporary art will be used to define the latest artistic developments in China. Since the historical was once contemporary, and the contemporary will one day become historical, this book attempts to transcend a linear narrative of art history, and instead, through a cultural perspective, to understand Chinese artistic development beyond the Western context, for a new insight into Chinese art contributing to the globalized art world.

Arts and culture started to be developed afresh after the death of Mao Zedong, the founder of the Peoples Republic, and the end of the Cultural Revolution, in 1976; and, in particular, after the policy of Reform and Opening (gaige kaifang) was confirmed at the Third Plenum of the 11th Central Committee of the Communist Party of China in December 1978. During the first three decades of the Peoples Republic (founded in 1949), art, following the doctrine of Maos Yanan Talks, had been through a transformation or nationalization from the Soviet Socialist Realist style, for instance, to a more localized style often with a sophisticated label, such as Revolutionary Realism or Revolutionary Romanticism. With attempts to break away from this dominant and, indeed, only ideology in the post-Mao era, a range of art practices came into being, including what art historians have dubbed Scar Art (Shanghen yishu) and Native Soil Art or Rustic Realism (Xiangtu xieshi). Rather than depicting or idealizing a revolutionary world, artists started to reflect upon and expose the actual situation in China. Cheng Conglins Snow on a Certain Day of a Certain Month, 1968 is a frequently cited example, being one of the first pieces to expose the traumatic experiences of the Mao generation and their losses during the turbulent years. Equally of significance, young artists further explored ordinary lives and the minority people whom they had encountered during their years spent working in the countryside during the Cultural Revolution. Among widely cited works, Chen Danqings Tibetan Series and Luo Zhonglis 2-metre-high (over 7 ft) photorealistic painting Father are most representative of the turn from scar to native soil. These artists were not just yearning for rural and natural life; they were, more importantly, translating reality into something symbolic or monumental, as well as examining and revealing human values in everyday existence. The legacy of realism has continued.

When did art become contemporary in China? From the end of the 1970s, many art groups emerged, and sixteen unofficial art exhibitions took place across the country, in Beijing, Shanghai and Xian. These spontaneously organized exhibitions for instance, Nature, Society and Man by the April Photography Society (opened 1 April 1979), and the first show of the No Name Painting Society (opened 7 July 1979) were deliberately apolitical in order to seek out pure art.Star Art Exhibitions (Xingxing meizhan) in 1979 and 1980. The Star group was initiated by the two core members Huang Rui and Ma Desheng, and the first exhibition consisted of work by twenty-three artists in total, including Wang Keping, Qu Leilei and Ai Weiwei. By rejecting the highly polished Socialist Realist style, and the approach of decorating revolutionary and political events, the Star group broke the silence. Unlike in other unofficial exhibitions, the Star artists did not keep their distance from politics and the established ideology of Maoist art; in other words, they did not stay neutral or seek only to convey artistic values beyond revolutionary aesthetics. Instead, they appeared to be explicitly political and critical, and they defined an independent position further from the official Chinese art world than any other since 1949.

Next page