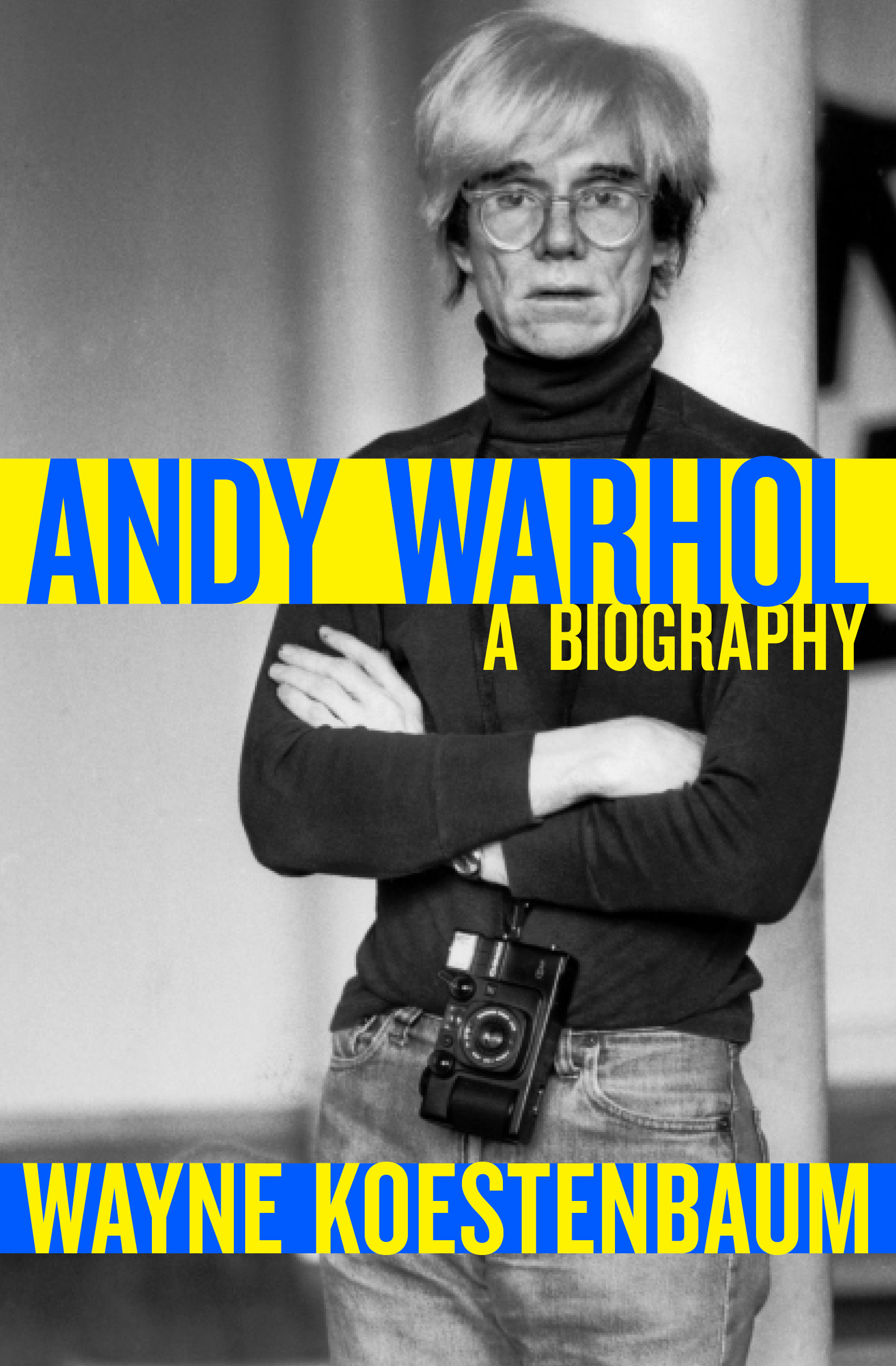

Andy Warhol

A Biography

Wayne Koestenbaum

All rights reserved, including without limitation the right to reproduce this book or any portion thereof in any form or by any means, whether electronic or mechanical, now known or hereinafter invented, without the express written permission of the publisher.

Grateful acknowledgment is made for permission to use the following copyrighted works: Correspondence from Andy Warhol to Julia Warhola and from Andy Warhol to Tommy Jackson from Correspondence files, Archives of The Andy Warhol Museum. Founding collection, The Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts, Inc.

Copyright 2001 by Wayne Koestenbaum

Cover design by Neil Alexander Heacox

978-1-4976-9985-4

This edition published in 2015 by Open Road Integrated Media, Inc.

345 Hudson Street

New York, NY 10014

www.openroadmedia.com

for Steven Marchetti

Contents

And when the crowd bent over him at the edge of the coffin, it saw a thin, pale, slightly green face, doubtless the very face of death, but so commonplace in its fixity that I wonder why Death, movie stars, touring virtuosi, queens in exile, and banished kings have a body, face, and hands. Their fascination is owing to something other than a human charm, and, without betraying the enthusiasm of the peasant women trying to catch a glimpse of her at the door of her train, Sarah Bernhardt could have appeared in the form of a small box of safety matches.

JEAN GENET, Funeral Rites

Introduction:

Meet Andy Paperbag

WORDS TROUBLED AND FAILED Andy Warhol, although he wrote, with ghostly assistance, many books, and had a speaking style that everyone can recognize because it has become the voice of the United Stateshalting, empty, breathy, like Jackies or Marilyns, whose silent faces sealed his fame. Warhol distrusted language; he didnt understand how grammar unfolded episodically in linear time, rather than in one violent atemporal explosion. Like the rest of us, he advanced chronologically from birth to death; meanwhile, through pictures, he schemed to kill, tease, and rearrange time.

Early in his career, he experimented with the sobriquet Andy Paperbaga reference to his tendency to carry drawings around in a paper bag. In imaginary conversations with him, as I try to reconstruct his life, I greet him as Andy PaperbagAndy, my bag lady, a sack over his head, concealing the features he disliked; Andy, stuffing a worlds refuse into tatty, woebegone containers.

Andy Paperbag didnt want to humble himself before words or time. As interpreter, I must make him submit to both. It is paradoxical to write a brief account of a person who pretended never to edit or condense. Every effort in his career as artist and whirlwind, as impresario and irritant, was to give the public too much, more than it wanted. Monumental, the pile of stufffilms, videos, paintings, photographs, prints, drawings, tapes, bookshe left behind for his mad widows to sort and comprehend; archivists and scholars will devote decades to unpacking, preserving, analyzing, selling, and quarreling over the mess. He left us too many hypotheses, too many images. Only a maniac or a masochist will want to absorb them all. His world is claustrophobically jam-packedwith people, artworks, collectibles, junkand so every visit to his sanctum hyperstimulates and exhausts the traveler: possibilities open to the point of electrical short circuit. Compared with Warhol, the other exhausting modern figures (Picasso, Stein, Proust) are manicured miniaturists.

Warhols selfhis paper baghad an odd shape, color, and consistency. It was slippery, elastic. It liked confusing itself with other bags, female and male, elderly and infantile. It had an imperial sense of domain: anything it saw, it conqueredby copying. It ignored everybody elses puling, tame ideas of normal behavior.

The story of Andy Warhol is the story of his friends, surrogates, and associates. It would be easy to narrate his life without saying much about him at all, for he tried to fade into his entourage. He had a peculiar style of treating people as if they were amoebic emanations of his own watchfulness. In practice, his friends or collaborators often found themselves erasedzapped into nonbeing, crossed off the historical record, their signatures effaced, their experiences absorbed into Warhols corpus. To work for Warhol was to lose ones name. Nathan Gluck, Warhols most important assistant from the 1950s, often forged the bosss signaturewhen the artists mother, Julia Warhola, wasnt in the mood to do it. Andy liked to entrust others with the task of embodying Andy.

Some members of Warhols circle were erased; others were given animation, charisma, and a possible immortality by their connection with this near-albino fairy godmother, who sprinkled diamond dust on their foreheads. Other people were the messy experimental material whose din and plumage filled Warhols empty canvas, screen, and page. He demanded collaborators; for every artistic or social act, he aggressively used other people as instruments and buffers. His works major theme was interpersonal manipulation, sociabilitys modules at war; without accomplices to co-opt and hide behind, he would have had no art. Many of the people Ive interviewed, who knew or worked with Warhol, seemed damaged or traumatized by the experience. Or so I surmise: they might have been damaged before Warhol got to them. But he had a way of casting light on the ruina way of making it spectacular, visible, audible. He didnt consciously harm people, but his presence became the proscenium for traumatic theater. Pain, in his vicinity, rarely proceeded linearly from aggressor to victim; trauma, without instigator, was simply the air everyone around him breathed. To borrow a religious vocabulary, often useful in Warhols case: he understood that people were fallen. Standing beside him, they appeared more deeply fallen, even if his proximity, the legitimacy he lent, the spark he borrowed and returned, promised them the temporary paradise of renown.

Despite the loyalty, infatuation, and transference that Warhols associates felt, few seem to have entirely loved him. Love may be a vague, rabble-rousing word, but it is impossible to weigh a life without using it. I first understood the loveless vacuum surrounding Andya blankness that was his creation, though he was also its victimwhen I read some letters written to him in June 1968, while he was convalescing in the hospital from gunshots. (The letters are at the Andy Warhol Museum Archives in Pittsburgh, along with the rest of his papers.) If I had been critically wounded, I would have wanted warmer commiserations; it seems that even his friends imagined Andy to be a bank momentarily closed because of a flood, the account holders congregated grumpily outside. Andy had friends, and many said they loved Andy, but no one (with the possible exception of his mother) could look after him. (Here I fall into sentimentalitythe kitschy land where Andy dwelled, despite his reputed coldness and his dread of the corny.) Stars are often isolated; as a consequence of his stardom, Warhol was cut off from reciprocity, like an autistic, or a pet in a box. Abjection suited him; he knew the weirdos experience of being insulted, rebuffed, and disliked. Nothing overcame this trampled sensation, not even the worldly power he acquired. In fact, his trauma backlog grew. Although his rise to fame in the early 1960s as a Pop artist gave him a lasting notoriety that gratified him, the subsequent decline of his artistic reputation, and the instabilities of his private life, reinforced his fundamental experience of being hated, and ensured that he would leave the earthprematurely, in 1987with a conviction that he had never belonged to it.