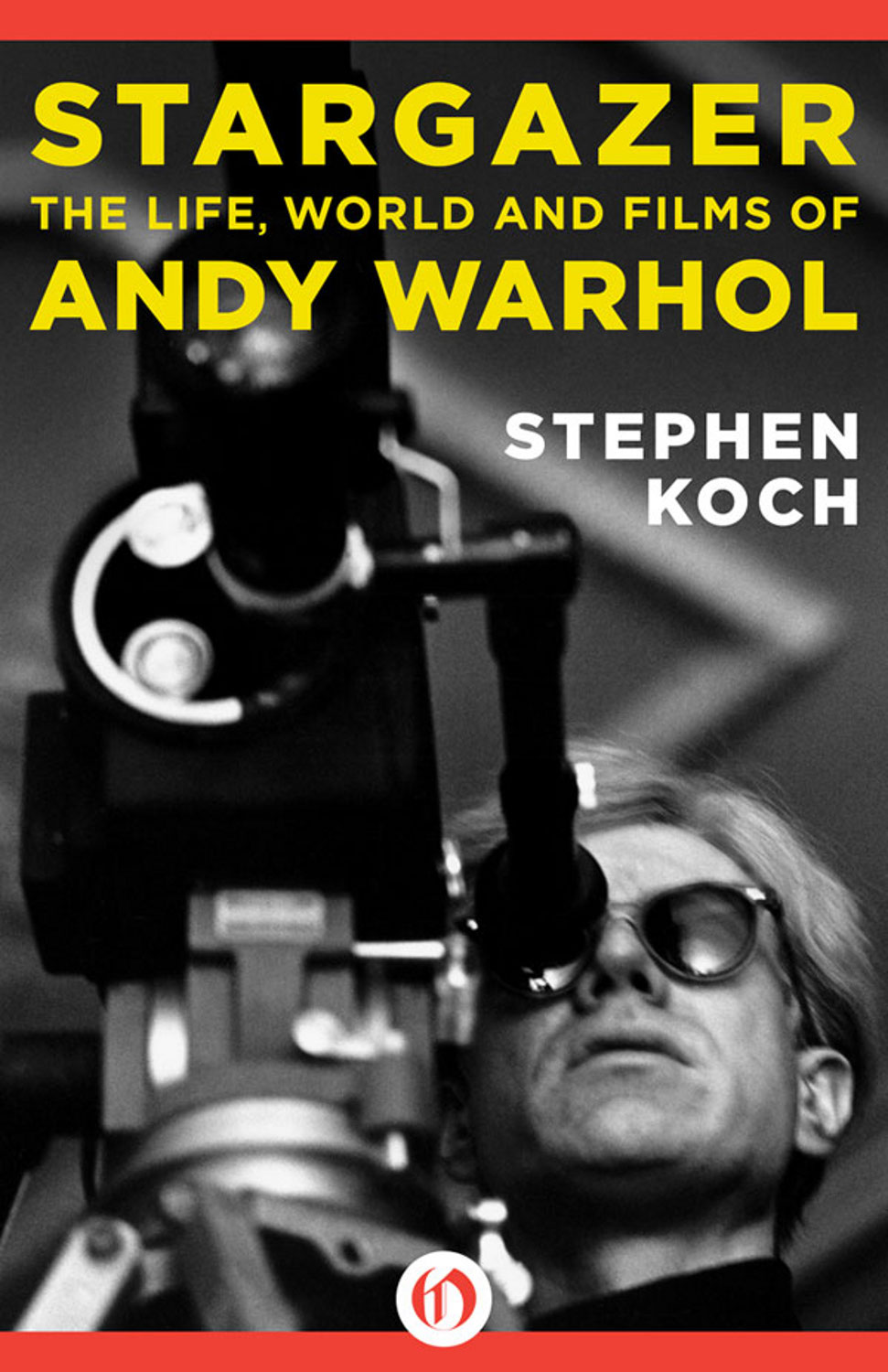

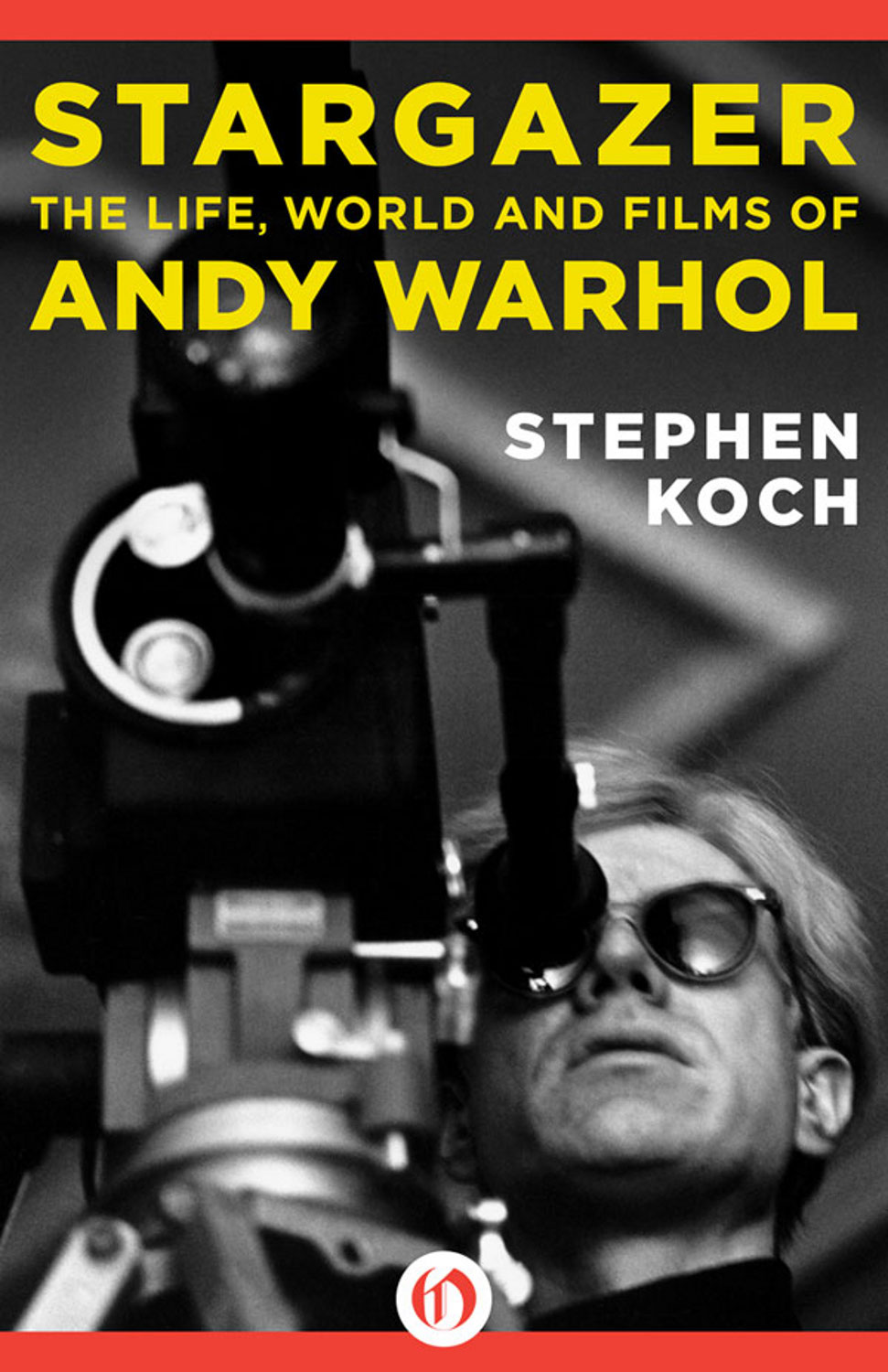

Stargazer

The Life, World and Films of Andy Warhol

Stephen Koch

I

ENDINGS

1.

Grace Rescinded

AFTER THE DEATH OF Andy Warhol on February 22, 1987, almost everyone in New York agreed that life would never be the same. Wherever one went, people sighed about eras ending, and with reason, I suppose. For over 20 years this cool, greatly gifted, wonderfully ingenious imp of the perverse had been at the center of those interlocking worlds of society and art which in 1987 were passing through dark times. Something did seem to be coming to a conclusion, and doing so in tragedy.

Warhol died in New York Hospital following otherwise uneventfulalbeit emergencysurgery performed the day before to remove his gall bladder. The need for such an operation had been obvious to his doctors for years, but Warhol had used all his many powers of evasion to resist the recommendation, gripped by a phobic belief that he would never survive it. Hospitals had been for him a source of terror ever since 1968, when a member of his entourage, a woman named Valerie Solanas, had attempted to shoot him to death in his studio on Union Square. Warhol had been desperately wounded. Three bullets penetrated many vital organs; on the surgical table his heart actually stopped beating until the surgeons emergency heart massage revived him. In Warhols sense of things, he had died and then been brought back, as if God had reconsidered and returned his life on loan. His life had been restored in a tentative amnesty, an act of grace, a revocable freebie. He would live the rest of his life feeling a precisely formulated sense of metaphysical specialness, and an accompanying metaphysical terror. He was breathing on borrowed time; his period of grace might be annulled at any moment.

As for hospitals, he was sure that if he ever returned to one, that would be it. His fear was so acute that Warhol could not bring himself even to pronounce the word hospital: he spoke instead of the place, as in they are trying to send me to the place. He made it a point never to pass a hospital, and he would never under any circumstances visit a friend in a hospital. Taxi drivers were often given elaborate instructions for avoiding even driving by the place, and if for some reason he was forced to pass one he would avert his eyes. And he would never go back. He would die there, he just knew it.

But in February 1987, Warhols gall bladder condition was close to critical. His doctors could no longer humor his evasions, and he could no longer sidestep his agony. He was told that without the prompt removal of his gall bladder he would probably die. Emergency surgery was scheduled for a Saturday, February 21.

A cholecystectomy is a serious but not unusual form of surgery, and Warhols went very well. When he emerged from the recovery room that afternoon, he was awake and reasonably cheerful. He spoke to friends on the telephone, he watched some television, he joked with his nurses. Then he slept.

And then, before dawn, around 5:30 the next morning, his private-duty nurse (who it appears either had left the room or fallen asleep) suddenly became aware that her patient was in severe crisis. Warhols always-pallid skin had turned blue; his breath was faltering he was unresponsive. The room was abruptly crowded with shouting interns and nurses in full emergency, but nothing helped. Within half an hour, it was clear that he was not going to make it. The reprieve of 1968 had been rescinded.

But it was a time for dying. In August 1988, Jean-Michel Basquiat, a young artist whose rapid rise took place very much under Warhols patronage, was found in his apartment lying in his own vomit, dead of a drug overdose. Three years after Warhols death, Keith Haring, the graffiti artist who had been among the last young artists assisted into a grand New York high-style success in fashion and finance by Warhol, was dead at the age of 31, a result of complications from AIDS.

Twenty years before, little bespectacled Keith, a smallish 10-year-old, gaped at one of Warhols Marilyn Diptychs in the basement gallery of the Hirshhorn Museum. The boy was in Washington on a trip with a church group from his hometown in Kutztown, Pennsylvania. This was little Keiths first look at art, his first conception of what art was, of what being an artist might mean. The moment Haring was old enough, he moved to live in the New York where Warhol was master. Inspired by what he saw as Warhols populism, Haring began by making his mark (literally making his mark) in the New York subways. Haring would descend into the underground stations in the dead of night, supplied with chalk and black background paper. He pasted the paper over advertising spaces on the platforms. When morning came, the trudging workaday traffic would find, in the sundry outposts of underground Manhattan, graffiti drawings of the figure Haring called Radiant Baby, a cryptic white-on-black cartoon of a crawling infant from whom chalky startled beams of joy seemed to be breaking loose. Bright in their black and white, pasted to the populist ills, and the pictures advertised nothing but new birth. They were unsellable, but it was exposure.

Three years after Warhols death, Keith Haring would be gone too, dead at right around the same age that Warhol had become a famous man. Warhol was the validation and most active support of what I do, Haring said when the master died, and his Radiant Baby turned out to be an image less of new life but of an age of farewells.

In a sense, Warhol died twice, and in a parallel sense he always seemed to be ending some era or other. I would argue that this was very much part of who Warhol was. There was something subtly valetudinarian about his very presence, something in the immediacy and vanguard freshness of his work that continuously foreshadowed its own end, something in the implicit pathos of his estheticized immediacy that was, with shy ingenuousness, waving a kind of perpetual goodbye.

2.

The End of Art

IMMEDIACY IS TRANSIENCE. This moment is forever about to become that moment. One could hear Warhols sense of the pathos of this truth even in his comments on his artistic immortality. His expectations for his work after he was gone were modest: I know my work wont last. A few years, at the most. I know that.

That admission of transience has not proved to be correct. Decades after his death, Warhols art and myth are anything but forgotten. His work is regularly knocked down at stupendous, front-page auction prices; his reputation still orbits around Picassos, generating perplexity over which of them is the most famous artist of the 20th century. Despite his own prediction of disappearance after death, the Warhol phenomenon has grown steadily. His posthumous presence is durable.

In 2013 the Warhol Museum in Pittsburgh clinched his immortality with a bit of spectral technology. Warhols body lies near those of his parents in the cemetery of Saint John the Baptist Byzantine Catholic Church in Pittsburgh. The site is often stacked with mementoesas often Coke bottles and Campbells soup cans as bouquets of flowers. The grave has many visitors. The stone bears the name Warhol, rather than Warhola on other graves; the original Czech family name was brought to America from a wretched little one-street country town in northeastern Slovakia when his penniless Ruthenian parents emigrated before he was born.

Next page