Table of Contents

Matthew Specktor

The Sting

MATTHEW SPECKTOR is the author of a novel,

That Summertime Sound. He lives in Los Angeles.

also available in this series:

They Live by Jonathan Lethem

Death Wish by Christopher Sorrentino

Lethal Weapon by Chris Ryan

The Bad News Bears in Breaking Training by Josh Wilker

Heathers by John Ross Bowie

For Virginia Specktor

The Sting

Americans hate to be fooled. We like our guys and our eyes wise, and prefer to believe, courtesy of our native optimism, that we learn from our experiences, are toughened up sufficiently so that adulthood means no longer being anybodys sucker. Its part of our national pretense, even ifas Hegel put ithistory teaches us that history teaches us nothing. We may have fallen for it way back when Charles Ponzi founded the Old Colony Foreign Exchange Company in 1919, or when George C. Parker made a habit of selling the Brooklyn Bridge to tourists around the same time; perhaps a little later, by way of Frank Abagnale (1960s) or Clifford Irving (1970s), or even Lou Pearlman (yes, the 1990s boy band impresario... currently doing twenty-five years for operating a Ponzi scheme of his own), but now that Bernie Madoff is finally behind bars, we can be sure that itll never happen again. Next time, oh next time, well indeed know better.

Whether or not we do, theres a reason why Charlie Browns failed swipe at the football is such an enduring piece of American iconography. Theres pleasure in being fooled, and a far greater dignity in thatin knowing youre going to take the fall and yet taking it anyway (I think of the end of Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid, the melancholy jubilance with which Redford and Newman charge their fatally armed pursuers) than there is in refusing the game. No one in this country likes a quitter, or a whiner. You pays your money and you takes your choice, says one of the rogues in that gallery of cons in Adventures of Huckleberry Finn. Imagine Charlie Brown turning away from the football and telling Lucy to take a hike. You can picture it, cant you? The voice that emerges from Charlie in that case is different, gum-cracking: It is Lucys voice, that of cynicism and authority, and while the whole world of Peanuts presents Lucy Van Pelt as Charlies A-number-one foil (besides the dog, that mute dreamer, writer, and pilot whose role seems more like an audiencesall comment and woolgathering observation), Leiber and Stoller didnt exactly celebrate her in a song, did they? Gullibility isor at least it was oncealso a virtue. Losing, too. There was a sense of dignity in loss, a greater nobility, perhaps. The glum schmucks who populate the wetter edges of the Sinatra catalog, the shattered souls who crawl along the gutters of Hollywoods original Golden Agebruised Bogarts, Cagneys, and Robinsonsall seem to know this, and if its possible Im being nostalgic (maybe Michael Bay is right, and it really is all about who gets to fuck the prom queen), nostalgia seems a fitting place to enter consideration of The Sting, a movie that comes wrapped, after all, in a handsome jacket of the same. Old-timey, good-timey, the films much-remarked-upon romanticizing of a bygone past is, to some extent, a feint: The Sting is as tough-minded as so many other contemporaneous odes to paranoia. Having conceived the script in the thick of an economic downturn and written it while the Watergate scandal was blowing up in the papers (is it an accident that the films central con is called The Wire?), screenwriter David S. Ward recollects that he was drawn to con men as a subject for being moral outlaws, for their existential loneliness and isolation. He wrote the script on a steady diet of urban blues, trying to evoke, through John Lee Hooker and Bessie Smith, a whole landscape of hardscrabble, Depression-era moods. In this respect, The Sting is very much in keeping with its neighbors, the ethical and cultural cinematic torpedoes that famously began battering Hollywood tradition just a few years earlier. As imagined, the film wouldnt have been far from Bonnie and Clyde.

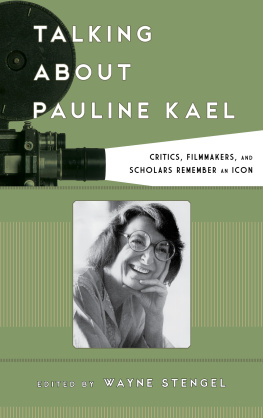

Except, of course, it was. High-spirited, playful, blessed with the mixed fortune of having a pair of stars whod already appeared together in one hit, the film was met with appreciation... comingled with suspicion and, in some places, hostility: It has been deemed lightweight. In their enthusiasm, certain critics couldnt resist pointing out the inevitability of its box office haul. Others outright hated it. This isnt a movie, its a recipe, Jay Cocks groused in Time, and Charles Champlin and Pauline Kaelwhose singularly obtuse contemplation of the movie deserves special mentionfelt the same. And yet the movies possession of a sense of fun, its very light-handedness (without which, no grift would succeed), suggests to me that some people might have mistaken self-knowledge for cynicism. The Sting wasnt about taking the audience for a ride. It was about, rather, how films (and other things) take audiences for a ride; its about confidence and belief, two themes whichmaybewere a little close to home in 1973 for certain people to see clearly.

In her essay On the Future of Movies, published in the August 5, 1974, issue of The New Yorker, Kael explicitly contrasts Bonnie and Clyde, The Graduate, Five Easy Pieces, M*A*S*H, They Shoot Horses, Dont They? and Easy Ridermovies that helped to form the counterculturewith The Sting, which she calls a soft fur collar that [executives] caress themselves with. Fascinatingly, the essay frames, without much skill, an argument The Sting itself treats with superior dexterity. Theres a natural war in Hollywood between the businessmen and the artists, Kael writes, with astonishing quaintness. Its based on drives that may go deeper than politics or religion: on the need for status, and warring dreams. The entrepreneur has no class, no status... in no other field is the entrepreneur so naked a status-seeker. This last assertion is debatable, but in any event, The Sting knows all this. (Kaels description of the entrepreneur mirrors David Wards description of the films villain, Doyle Lonnegan.) The essay goes on to speak explicitly of confidenceBut almost any straw in the wind can make [the entrepreneur] lose confidence in riskier films... the businessmens confidence has taken a leap... theyve got the artists where they want themand how perhaps no work of art is possible without belief in the audience. Yet somehow The Sting, six steps ahead of Kael at every turn, bears the brunt of it. Contrasting Hills movie against an idea film like Frances Coppolas The Conversation, Kael finds the former wanting. Hill believes in big-name, big-star projects. The artist bucks the system, which only works for thoseshe names Hill and William Friedkinwho dont have needs or aspirations that are in conflict with it.

Quite an indictment, and wrong on every level. Still, one thinks of those movies Kael names at the beginning of her essay and othersI mark them as contemporaries of