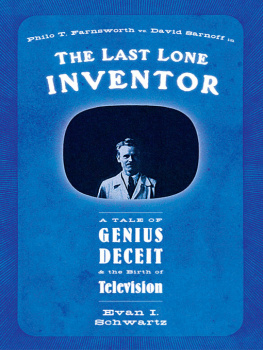

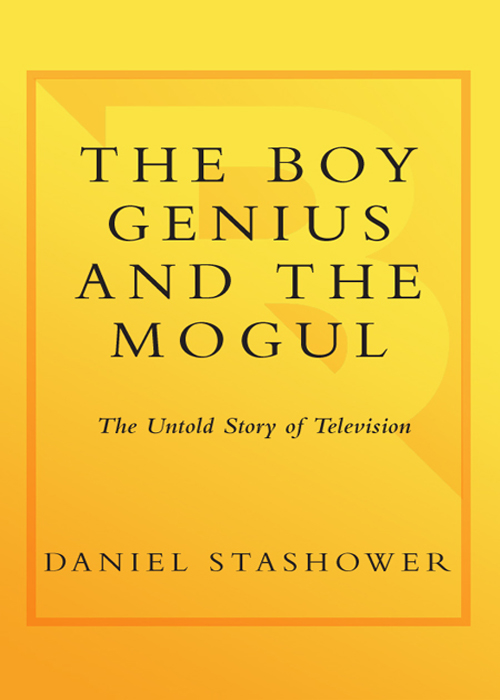

The Boy Genius

BROADWAY BOOKS / NEW YORK

and the Mogul The Untold Story

of Television Daniel

Stashower |  |

Contents

One

The Death of Radio

Two

The Laboratory Pest

Three

The Messenger Boy

Four

Light from a Distant Star

Five

Tilting at Windmills

Six

The Battle of the Century

Seven

The Ideas in This Boys Head

Eight

Photographs Come to Life

Nine

Dollars in the Thing

Ten

A Beautiful Instrument

Eleven

Priority of Invention

Twelve

Now We Add Sight to Sound

Thirteen

The Lawyer Wept

Preface

An artists impression from a 1918 magazine offers a glimpse of how a future television device, dubbed the telephot, might operate. THE ELECTRICAL EXPERIMENTER

Television? The word is half Greek and half Latin.

No good will come of it.

The Manchester Guardian

I n 1910, when my grandmother was seven years old, Hugo Gernsback would come to the house and make alarming predictions about a device he called the telephot. My grandmother was then living on Central Avenue in Cleveland, and Gernsback, a favorite cousin, often stopped off on his train trips from New York to Chicago, where he went to purchase radio equipment for his electrical parts company.

Gernsback had not yet attained fame as a pioneer of science fiction, a term he is sometimes credited with having coined. His principal achievementsAmazing Stories magazine, of which he was the founding editor, and a truly awful science fiction novel entitled Ralph 124C 41+still lay in the future. Already, however, he had cultivated a certain imaginative flair. A lean, dapper man who favored expensive suits and bright silk ties, Hugo would arrive with a giant box of Schraffts chocolates under his arm and spin out wild tales of the future and the marvels it would bring. Robot doctors, retirement colonies on Mars, domed cities orbiting the earthall of these were just around the corner. If a ringing telephone interrupted one of his stories, he invariably raised a finger of caution at my grandmother. Hildegarde, he would say in his thick German accent, fix your hair. It wont be long before the caller can see your face over the telephone wires.

The notion of a device that would enable one to see objects at a remote distance had been in play for many years at this point. The word televisionfrom the Greek for far and the Latin for seeinghad begun to surface in learned journals and scientific texts, though a number of other phrases were also used to describe the strange concept: hear-seeing, audiovision, visual listening, radiovision, and telephonography. Gernsback himself initially favored telephot, though the word television crept into a 1909 issue of his Modern Electrics magazine, prompting a later claim that before that time the designation had never been used. Family pride notwithstanding, I am constrained to admit that the term had already appeared in print at least ten years previously.

There are certain inventions which, although not yet existent, we may take for granted will be invented some day, Gernsback wrote in his Electrical Experimenter magazine in 1918. That they have not already appeared is by no means the fault of science, but simply because certain minor phases in the various endeavors have not as yet advanced sufficiently to make such inventions possible. Television, or remote seeing, is one such invention. That such an invention is urgently required is needless to say. Everybody would wish to have such an instrument, and it is safe to say that such a device would revolutionize our present mode of living. Numerous inventors have busied themselves trying to invent an apparatus or machine whereby it would be possible to view visual scenes from a great distance. Strangely, the general public is not aware of their struggle, or the frontiers of science that they are seeking to conquer.

Stranger still, more than eighty years later, the story of that struggle remains largely unknown. The general public has only the vaguest notion of howor by whomtelevision was created. Stop the average person on the street and he or she will be able to tell you in an instant who invented the lightbulb, or the telephone, or even the cotton gin. But the origin of television, an invention that did as much as any other to shape the twentieth century, is largely unknown. The names of Philo T. Farnsworth and Vladimir Zworykin occasionally pop onto the screen, but the overall picture remains fuzzy.

It is fair to say, as Gernsback predicted, that remote seeing did, in fact, revolutionize our present mode of living. In the wake of the World Trade Center and Pentagon disasters it is perhaps unnecessary to deliberate over the power of television, or review the many ways in which it has shaped the world. Much has been written about the impact, both good and bad, of televisions omnipresence and immediacy, from the Nixon-Kennedy debates and Vietnam to O.J. and Jerry Springer. What is often lost, however, beneath the bland and often stupefying effect of televisions usual content is the revolution contained within its tubes and diodes. The men who invented television are not responsible for The Love Boat. Were in the same position as a plumber laying a pipe, David Sarnoff, the president of the Radio Corporation of America, once had occasion to remark. Were not responsible for what goes through the pipe.

The process of laying that pipe would prove to be one of the most dramatic scientific questsand bitter legal battlesof the electronic age. It has been argued that there was no single pioneer of television, and therefore no Kitty Hawk or Menlo Park, but rather a series of Eureka moments in various parts of the world. As with the development of space travel or the creation of the atom bomb, television is said to have evolved over a period of furious struggle and heated competition. That being the case, it is not surprising to find that there are many different versions of the story, each reflecting the self-interest of whoever is telling it. At the same time, the story tends to engender a great deal of flag-waving, and nearly every country in the world lays claim to the true and only Father of TelevisionKenjiro Takayanagi of Japan, Ren Barthelemy of France, Dionys von Mihaly of Hungary, Boris Rosing of Russia, and John Logie Baird of Great Britain. All of these men, and many others, played a significant role. None of them, however, managed to gather all of the various pieces together into one definitive box.

The fundamentals of that box had been glimpsed a generation earlier by such nineteenth-century pioneers as Joseph May, who discovered the strange light-sensitive properties of the chemical selenium in 1872, and Paul Nipkow, who in 1884 patented a mechanical process of image-scanning that would form the basis of television experimentation for decades to come. Matters took a strange turn in 1880, when Alexander Graham Bell deposited a sealed dossier concerning a device called a photophone with the Smithsonian Institution. A rumor arose that the famed inventor of the telephone had now perfected a means of seeing by telegraph. In fact it was nothing of the sortBell was experimenting with the transmission of speech by means of a beam of lightbut the mere suggestion of an Alexander Graham Bell distant viewer prompted a mad rush of inventors publishing their results. It is pleasant to note that in August of 1904 a patent application for a color television system was filed, by an inventor named Frankenstein.

Next page