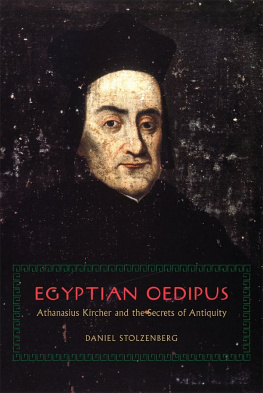

DANIEL STOLZENBERG is assistant professor of history at the University of California, Davis.

The University of Chicago Press, Chicago 60637

The University of Chicago Press, Ltd., London

2013 by The University of Chicago

All rights reserved. Published 2013.

Printed in the United States of America

22 21 20 19 18 17 16 15 14 1 2 3 4 5

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-92414-4 (cloth)

ISBN-13: 978-0-226-92415-1 (e-book)

ISBN-10: 0-226-92414-9 (cloth)

ISBN-10: 0-226-92415-7 (e-book)

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Stolzenberg, Daniel.

Egyptian Oedipus : Athanasius Kircher and the secrets of antiquity / Daniel Stolzenberg.

pages cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 978-0-226-92414-4 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 0-226-92414-9 (cloth : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-226-92415-1 (e-book) ISBN 0-226-92415-7 (e-book) 1. Kircher, Athanasius, 16021680. Oedipus aegyptiacus. 2. Egyptian languageWriting, Hieroglyphic. 3. Occultism. I. Title.

PJ1093.K643S76 2013

493.1092dc23

2012022898

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

EGYPTIAN OEDIPUS

Athanasius Kircher and the Secrets of Antiquity

DANIEL STOLZENBERG

THE UNIVERSITY OF CHICAGO PRESS

CHICAGO AND LONDON

HIEROGLYPHICS Language of the ancient Egyptians, invented by the priests to conceal their shameful secrets. To think that there are people who understand them! But perhaps the whole thing is just a hoax?

Gustave Flaubert, Dictionary of Received Ideas

C ONTENTS

A NOTE ON QUOTATIONS AND TRANSLATIONS

Since virtually all the early modern books that I quote, including some of the rarest and most obscure, have recently become easily available online, especially through open access sites like Gallica, the Hathi Trust, the Munich Digitization Center, the Internet Archive, and Google Books, in the footnotes I have provided original text only for significant quotations from unpublished manuscripts. Unless otherwise indicated, all translations are my own. For ease of reading, I have translated the titles of books into English; the original titles are given in the footnotes.

A BBREVIATIONS

| APUG | Archivio della Pontificia Universit Gregoriana |

| ARSI | Archivum Romanum Societatis Iesu |

| ASV | Archivio Segreto Vaticano |

| BAV | Biblioteca Apostolica Vaticana |

| BNF | Bibliothque Nationale de France |

| BNCR | Biblioteca Nazionale Centrale di Roma |

| BISM | Bibliothque interuniversitaire (Montpellier), Section Mdecine |

| LAR | Athanasius Kircher, Lingua Aegyptiaca restituta (Rome, 1643) |

| PC | Athanasius Kircher, Prodromus Coptus (Rome, 1636) |

| OA | Athanasius Kircher, Oedipus Aegyptiacus (Rome, 165254) |

| OP | Athanasius Kircher, Obeliscus Pamphilius (Rome, 1650) |

| Vita | Athanasius Kircher, Vita Admodum Reverendi P. Athanasii Kircheri in Fasciculus Epistolarum, ed. Hieronymus Langemantel (Augsburg, 1684) |

I NTRODUCTION

Oedipus in Exile

The wisdom of the Egyptian philosophers truly seems to be something much too divine to be understood by any little man; for, in my opinion, the Egyptian system of the world, which was based on the laws of attraction and repulsion, seems to be the closest of all to the truth. This opinion of mine now has the consent of all Europe, which approved it not so long ago, but attributed it to Newton, in his calculus. But Kircher came before Newton; and lest someone thinks that I am daydreaming, I would have him read carefully and with an unprejudiced mind those things that Kircher wrote in the last chapter of Coptic Forerunner and Egyptian Oedipus.

Adam Frantiek Kollr (1790)

MALTA, 1637

The summer of 1637 found Athanasius Kircher (1601/21680) marooned on

While Kircher made desultory efforts to instill Frederick with Catholic piety, back in the mainstream of European intellectual life, Ren Descartes (15961650) published his first book. A Discourse on the Method for Conducting Ones Reason Rightly of traditionalists and rallying cry of moderni.

Descartes famously attributed his breakthrough to a period of forced isolation. Serving in the army of Prince Maurice of Nassau, he was detained one winter in Germany, where he found himself with abundant free time and few external distractions, such as books or conversation partners. One momentous day, alone with his thoughts in a stove-heated

Kircher did not find isolation so stimulating. In Rome, he had thrived at the bustling Collegio

THE HIEROGLYPHIC SPHINX

Like Descartes, Kircher went on to achieve considerable, if less enduring, fame in the international community of scholars that called itself the Republic Even when challenging orthodoxy, however, Kircher remained faithful to the veneration of antiquity that was the common legacy of humanism and scholasticism.

This book explores one part of Kirchers encyclopedic corpus: his study of Egypt and the hieroglyphs. After two decades of toil, Kircher

Fig. 1. Kircher as the Egyptian Oedipus before the hieroglyphic sphinx. See for an explanation of the symbolism. Athanasius Kircher, Oedipus Aegyptiacus (Rome, 165254), vol. 1, frontispiece. Courtesy of Stanford University Libraries.

This book presents a new interpretation of Kirchers project in terms of an encounter between two early modern intellectual traditions: erudition (antiquarian research and philology) and occult philosophy (the Renaissance Neoplatonic tradition, based on a lineage of esoteric wisdom attributed to extremely ancient pagan wise men). Kirchers spectacular shortcomings have made it difficult to appreciate how much he participated in the important scholarly developments of his time. Once his proper measure is taken, he proves a useful figure for reassessing important aspects of seventeenth-century scholarship. By reading his hieroglyphic studies as a work of erudite historical research, instead of philosophy, I show that Kircher differed fundamentally from earlier writers in the so-called Hermetic tradition, whose work he has been seen as continuing, and that he shared more with his contemporaries than has usually been acknowledged. Egyptian Oedipus was not quite so monstrous as Manuel imagined. In particular, I argue that Kirchers use of occult philosophy in the service of antiquarian research was not anomalous, and that the prevailing chronology of the fate of occult philosophy must be revised. Behind Kirchers two greatest failureshis incredible translations of hieroglyphic inscriptions and his reliance on spurious documentslay widely accepted principles about symbolic communication and the transmission of ancient knowledge. As a case study of seventeenth-century scholarship, this book illuminates a complex moment when empiricism and esotericism coexisted, and shows how the discipline of Oriental studies was born from an early modern Mediterranean world in which texts, artifacts, and scholars circulated between Christian and Islamic civilizations.

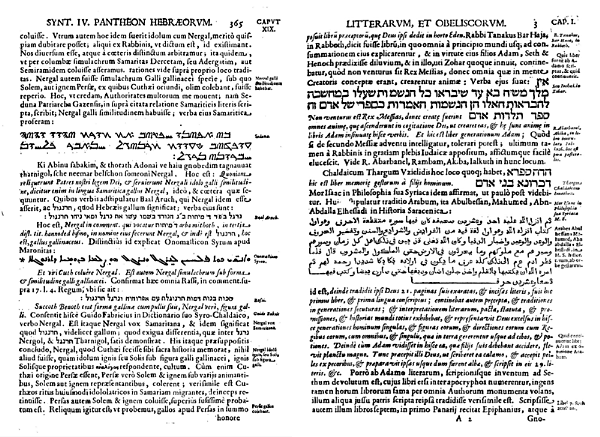

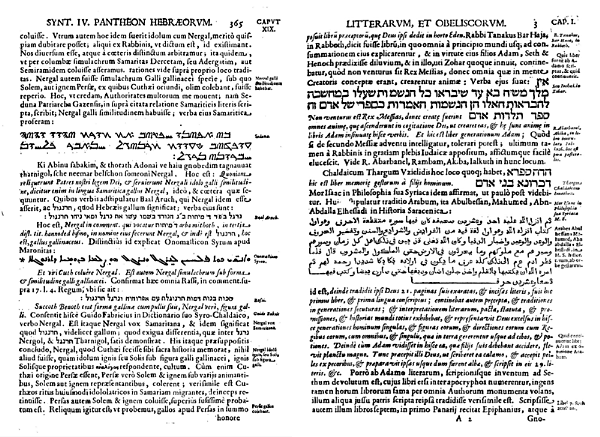

Fig. 2. Quotations in Samaritan, Syriac, Hebrew, and Arabic embedded in Kirchers Latin exposition. Such typography was expensive and technologically challenging in the seventeenth century. Athanasius Kircher,

Next page

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).

This paper meets the requirements of ANSI/NISO Z39.48-1992 (Permanence of Paper).