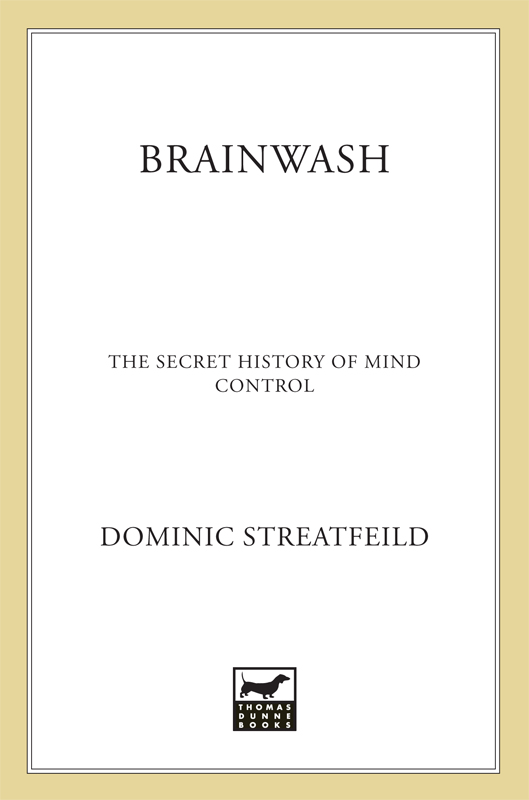

The author and publisher have provided this e-book to you for your personal use only. You may not make this e-book publicly available in any way. Copyright infringement is against the law. If you believe the copy of this e-book you are reading infringes on the authors copyright, please notify the publisher at: us.macmillanusa.com/piracy.

Contents

For my parents

Brain Warfare

IRAQIS DRUGGED, BRAINWASHED AND SENT TO DIE FOR BIN LADEN FROM JAMES HIDER IN KARBALA

Terrorists linked with al-Qaeda are increasingly recruiting young Iraqis to carry out suicide bombings, brainwashing them with Osama bin Ladens sermons and drugging them before sending them off to wreak mayhem, Iraqi police believe.

The Times, 22 March, 2004

I couldnt believe it. My son had gone from a docile mouse to a suicidal killer? No. Not without being brainwashed. Someone got to him. I am sorry to say it, but he was brainwashed.

Robin Reid, father of shoebomber, Richard

Dr Andrs Zakar was returning from morning mass at Vizivros Convent on Sunday, 19 November 1948 when an unmarked car pulled up alongside him. Silently, three men in dark suits leaped out, grabbed the doctor by the arms and bundled him on to the back seat. They climbed in after him, slammed the doors and, with a screech of tyres, accelerated away.

To passers-by there was nothing especially remarkable about this incident. Hungarians had been told that the state was under threat and that conspirators were everywhere: the secret police were snatching dissidents more or less continously. What made this case unusual was the victim. Dr Zakar was personal secretary to Jsef Mindszenty, head of the Catholic Church in Hungary and the most senior cardinal in Eastern Europe. Mindszenty, a potential successor to Pope Pius XII, was a powerful man; the disappearance of his secretary was ominous.

Five weeks later the secret police returned Dr Zakar to the cardinals official residence in Esztergom. But the Zakar they delivered on Christmas Eve 1948 wasnt the same Zakar who had left the month before. Something had happened to him. His eyes looked strange. He was confused and disoriented, as if in a twilight state of consciousness. The normally taciturn thirty-five-year-old doctor of theology behaved like a child, babbling and giggling constantly. At one point he ran down the corridors, shrieking. Officers accompanying Zakar treated him like a madman, repeatedly reminding him that they fed him meat twice a week. In return, he simpered as if they were his closest friends. He seemed, recalled Gyula Mtkai, the cardinals chief secretary, to be having a very good time with them.

Ordered to search the building for incriminating evidence, Zakar took off at a gallop, leading the officers to a room in the basement where he pointed to a spot on the ground. Digging a few inches beneath the soil, the policemen discovered a metal box full of Mindszentys confidential correspondence. They then congratulated the smirking Zakar and shepherded him back to the secret police headquarters at 60 Andrassy Street in Budapest for more treatment.

At 6.45 p.m. on Boxing Day, Mindszenty and his elderly mother were making their way downstairs after evening mass when there was a furious banging at the door. The cardinal ordered it to be opened, to find himself facing a group of armed men. Lieutenant-Colonel Gyula Dcsi stepped forward. We have come to arrest you, he told Mindszenty. The cardinal asked to see the warrant but Dcsi shook his head. We dont need one.

Mindszenty knelt, kissed his mothers hand and said a prayer, then picked up his coat and hat and handed himself in to the custody of the arresting officers. The last sounds he heard as he was led away into the night were the voices of his colleagues who, realising that his arrest spelt the end of Catholicism in Hungary under Soviet occupation, had spontaneously started singing the national anthem.

Mindszentys staff were dumbfounded by his arrest but initially it was the behaviour of his secretary that most baffled everyone. How could the loyal Dr Zakar have betrayed the cardinal? Why had he behaved so bizarrely? Clearly, they thought, something strange had happened to him.

By the time he arrived in court five weeks later, something strange had happened to Cardinal Mindszenty, too. In the dock he swayed backwards and forwards, unsteady on his feet. His eyes were half closed and he was uncoordinated, like a sleepwalker. He spoke in a monotone, as if repeating facts by rote. At times he paused for up to ten seconds between words. Apparently unable to follow the course of his own trial, this highly educated, intelligent man stood, eyes glazed, totally bewildered.

Worse than his appearance, however, was what he said. As Mindszenty stared into the middle distance, he confessed that he had orchestrated the theft of Hungarys crown jewelsincluding the countrys most sacred relic, the Crown of St Stephenwith the explicit purpose of crowning Otto von Habsburg emperor of Eastern Europe. He admitted that he had schemed to remove the Communist government; that he had planned a Third World War and that, once this war was won by the Americans, he himself would assume political power in Hungary.

The confessions were patent nonsense. Since the end of the war, Mindszenty had indeed opposed the Communist takeover of Hungary but he was no revolutionary, and he certainly wasnt a traitor. At one point in court he agreed that he had met Otto von Habsburg in Chicago on 21 June 1947; in fact, Habsburg had not been in Chicago and the cardinal had not been in the United States on that date. Moreover, Western observers soon discovered that Mindszenty had specifically warned Church officials of his impending arrest by the Communists. Afraid that he might buckle under torture, he had written letters just weeks before he was picked up to the five most senior Catholic officials in Hungary with instructions that they were to be opened only in the event of his arrest. The letters stated categorically that he had not taken part in any conspiracy and that he would never resign his episcopal see.

Asked in court about them, Mindszenty appeared to have changed his mind. I did not see then many things which I see today, he slurred. The statement I made is not valid. He also offered to resign.

To those who knew him, Mindszenty had undergone a radical transformation. A source close to Pope Pius XII commented that the Mindszenty on trial was not the man that we knew. British Foreign Office analysis concluded that he was a tired or resigned man wholly unlike what we know of the Cardinals real personality. Even his mother agreed, telling the press that when she was allowed to see him in jail he was a completely changed man, without will and without consciousness. At one point when she visited him, he had failed to recognise her altogether.

The cardinals handwriting seemed to have changed, too. Comparisons of his signature before and after the arrest revealed considerable differences. According to an Italian graphologist, Mindszenty was no longer capable of writing his customary signature. Sure enough, in the month of the trial, two Hungarian handwriting experts, Laszlo Sulner and Hanna Fischhof, defected to Austria and confessed to working on the case. Initially, they said, they had been called in to forge the cardinals confessions but it soon became clear that this would not be necessary: he was signing them of his own accord. According to the two experts, documents emerging at the start of Mindszentys interrogation contained denials, but within a fortnight they were full of confessions. The mind which impelled the pen in the first instance, reported Sulner, was not the mind which impelled the pen in the second instance. Something strange, indeed, had happened to the cardinal.