Table of Contents

Adam Zagajewski

INTRODUCTION

I first met Professor Andrzej Szczeklik in Paris in the 1990s when my principal personal identification document (as well as a Polish passport) was still a French Carte de Rsident. This smiling, extremely sympathetic doctor made an excellent impression on me; we had only a short conversation, but at once I realized I was dealing with an unusual doctor and scholar, an experimental scientist and humanist all in one.

People who came from Krakow confirmed that I was not wrong; I heard about Szczekliks famous clinic, where in the best possible conditions ordinary people were treated in addition to famous artists, including Czesaw Miosz. I understood that Andrzej Szczeklik is as much a good Samaritan as he is a brilliant academic. Soon after our return to Krakow, my wife and I were witnesses to an extremely amusing, cabaret-style launch for the Professors book Catharsis. However, the book itself was serious; I was moved by its content, but also by the fact that the figure of the Author proved to be an extraordinary writer, combining sensitivity and humanist erudition with admirable expertise in the exact sciences (for, nowadays, medicine is this kind of science). I thought people like that had disappeared forever, and that we could only look back nostalgically into the past for universal authors who understand the life of the soul and the body.

I remembered that fifty years ago, in his famous lecture The Two Cultures and the Scientific Revolution, the British writer C.P. Snow fulminated on the fact that two spheres of learning (and education), the scientific and the humanist, had entirely parted company. He laid the blame at the door of the humanists (of course!).

I do not know who is to blame, or what the penalty should be, but the fact is, these two cultures have parted ways for good and all, and any author who tries to bridge this deep schism deserves attention and recognition. And if he does not try, we should be forgiving...

In past decades patients have often written about medicine; patients, or devotees of medicine such as the great Polish essayist Jerzy Stempowski, who was an amateur expert on pharmacology and medical procedures. In his beautifully written letters he occasionally imparted advice about health, or at least commented knowledgeably and sadly on the medical diagnoses given to his correspondents by professionals.

In some health care systemsin the United States, for example, where I have had occasion to seek a medical opinionthe doctor has changed into someone who appears before the patient for just a brief moment, like Zeus himself. The patient sits in a tiny little room with no windows, like a prison cell that has just been cleaned, and waits in solitude for quite a long time, until suddenly he hears a determined twist of the door handle, and there is God, in the person of a suntanned doctor, who asks two questions and then instantly vanishes. Before this revelation, and also after it, the patient is surrounded by an army of nursesgenial, jocular nymphs, but with no authority. Nowadays, the doctors face is not so very different from a computer screen, or the cover of a journal such as The Lancet or Nature, or a checkbook...

So we are all the more interested in a writer who, like Andrzej Szczeklik, belongs to the ranks of the initiated, is a practitioner and theoretician, is familiar with human suffering, and knows all about the genome and other recent discoveries in the field of molecular biology. He is extremely well versed in the history of medicine, which includes not only the fates of geniuses and charlatans, and the clandestine theft of bodies needed by pathologists, but also the unusual observations that have led to breakthroughs in science. Nor does he ignore other, soft questions, doomedjust for now, or for all eternity?to find no answer. Szczeklik writes with awareness of two kinds of problems: those that will one day be solved, and those that are sure to remain a mystery forever.

Humanists are often left helpless in the face of the big questions, but they could not manage without them. On the whole they regard representatives of the mathematical sciences with a touch of envy, knowing full well that in their own field there is not going to be any progress or sensational discovery for the worlds press to write about. After all, the basis of the humanities (including poetry) is patient contemplation of the world and of arta form of contemplation that does not involve any microscopes or X-rays, just the eye, the memory, and what Blaise Pascal called lesprit de finesse (which is translated as the intuitive mind).

What luck that we can still find an author who reads Dante, who understandsand sharesthe disquiet of ancient and modern poets, who is so well read in the humanities, and who also helps us to comprehend the complexities of the most up-to-date medical theory. What a pleasure it is to read a book that succeeds in combining a competent discourse on modern biology with the intuition of an artist who knows that the physical health we need and desire so much, and that some of us so tragically lose, is not everything, because to be a human being means to ask questions about tomorrow, about the soul, about the meaning of life, and about infinity. In other words, to be a human being (even a healthy one, even a young one) is to be eternally dissatisfied, and to seek books that make a topic and a building material out of that dissatisfaction, thanks to which, paradoxically, they do something to assuage it. Kore is just this kind of bookit is Andrzej Szczekliks very personal guide to medicine and the humanities, and also, to some extent, to his own recollections.

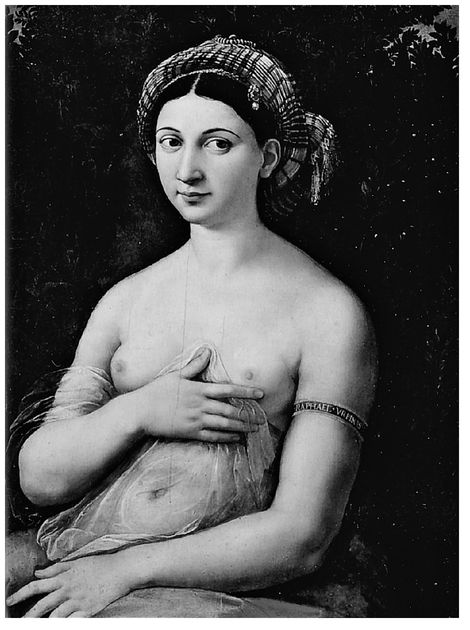

Raphael

La Fornarina, 1520

Galleria Nazionale dArte Antica, Rome

SYMPTOMS AND SHADOWS

To tap and to listen, to look and to feel,

To make the eyes open and seek out the soul,

To hear out the breathing, to see fleeting clues,

To grasp just how simple the crux of it proves.

Coming home one evening, Raphael felt unwell and was seized by shivering and fever. Even though he had never known illness before, he sensed the approach of death. He received extreme unction and wrote his will, and a few days later he was no longer alive. He died on Good Friday, on his thirty-seventh birthday, at the height of his fame and universal adoration. Before dying, he said farewell to the woman he loved, entrusting her care to his faithful servant. He left us her portrait. Her name was Margherita, and she was known as La Fornarina, because she was the daughter of a baker (or fornaio