For my father

We are the ones who carry out the dream. The dream that the supporters will never achieve because they cant play. So they live through us. But we have dreams we cant realise, too .

Kenny Dalglish, 2010

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

Theres something inherently sad about an autograph book sad in both senses of the word. Probably any sort of memento has a certain melancholy to it, but this ones a little pitful, too. Look at the state of those stale pages, devoted to dashed and oft-illegible signatures dubious evidence that you once grabbed the briefest encounter with some kind of a hero.

Thats only, mind you, if one has managed to keep something so organised as a book. Its not to speak of the sorts of autographs that get scribbled onto stubs, old receipts or whatever else you could produce from your pocket before the hero in question got away from your clutches, out the door or into the lift or VIP enclosure. Autographs are for kids, really, you would think on paper. And yet the habit persists into the adult world, much like all sorts of youthful practices. People in queues at book signings arent so far removed from this curious fever they seek the excuse to have a moment with someone special, and something tangible to take from it.

We all know that on some basic level a passion for football is boyish: it makes juveniles out of grown men, renders them prone to a terrible sentimentality. Go to any professional football training ground, into any changing room, and the hairy fug of testosterone and banter will leave you in no doubt that football remains a mans game. Its not massively more polite out in the stands. And yet, from whatever perch the modern fan looks out, the following of football seems to endure into adult life as a vehicle for somewhat arrested emotions what the psychologists call latency, or projection, or displacement.

This is by way of preamble to the confession that I have, in my time, stood and waited breathlessly for footballers autographs; and that, as a boy, the signature I coveted above all was the Kings.

It was July 1980, I was nine years old, and the setting was Jurys hotel in Dublin, at that time one of the fancier spots in town, where the Liverpool FC squad were staying in advance of a pre-season friendly with Dundalk at Lansdowne Road. My father had guessed rightly that I would love the chance to fill up my autograph book, and we found the foyer at Jurys crawling with young Dublin lads who clearly had the same idea as me. There were easy pickings to be had from assorted Liverpool first-teamers and squad resting at ease in the plush seating no bother spotting the permed heads of Phil Thompson or Terry McDermott. The roaming pack of boys into which I folded myself, though, went single-mindedly in search of Dalglish. We didnt even need to say as much it was implicit. Kenny was the big prize, the ubiquitous schoolyard hero, the top Panini card in the pack, no question.

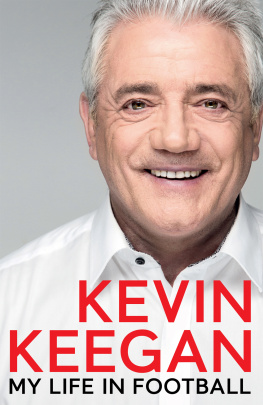

What was it Dalglish had, the way he did the thing he did? Is it shallow to admit that he looked great? In my childish mind that was part of the deal, for sure. The Umbro Liverpool kit of that era had a terrific lustre. Id never seen it look finer than in the Charity Shield match of 1979 when Liverpool tonked Arsenal 3-1, those red shirts aglow in the light of August, the white V-neck collars so pristine as to seem clerical. The scarlet of Dalglishs shirt found its analogue in the flush of his cheeks under his straw-coloured barnet; and stamped on his back was 7 the luckiest of numbers, the one hed inherited from Kevin Keegan two summers before, Keegan having moved abroad to better himself at SV Hamburg.

What really counted, of course, was the football, and above all the goals not just that Dalglish scored so many, and in such style, but also the unalloyed joy he clearly derived from it. His delighted celebrations arms aloft, big beamer of a grin were a major, major part of his appeal. As sportswriter Aidan Smith would reflect, years later, in the Scotsman , No one ever looked happier for having achieved the dream of every lad.

Still back to the aesthetics it did seem even to my juvenile self that you had to have a bit of the artist in you to truly savour the special finesse of Dalglishs goals. Always, he chose placement over power: he seemed to just stroke the ball towards the net, yet there was audacity and nervelessness in how he bet on himself to catch the keeper out. One of his best finishes was in that Charity Shield game against Arsenal, where he ran at goal, hotly pursued, only to check right so dumping a defender down onto his backside before clipping a perfectly measured side-footer to the far right corner.

Watching the game, in the flurry of the moment, it seemed to me that Dalglishs placement was magic: I imagined it was a gift as opposed to a craft, the result of long practice. I should have understood better the reasons why Dalglish was so often able to repeat the trick. In a game against Crystal Palace, for instance, surrounded by four hostile white shirts just a yard inside the box, Dalglish had dug the ball out of that mess of defenders and chipped it past the keeper onto a spot maybe six inches inside the right-hand post. Back then I just couldnt see the degree to which Dalglish actually depended on defenders to obscure the goalkeepers sight of the ball, so that he could curl it around the whole lot of them. (I couldnt know that Dalglish, when himself a nine-year-old, had learned the trick by studying Ian McMillan, inside forward for his beloved Glasgow Rangers.) But then, aged nine, I didnt realise Kenny Dalglish had been a professional footballer longer than Id been alive. I could see, though, that he was at the height of his powers.

Beyond the goals, Dalglishs precise passing was a wonder, too inspiring just as many artless playground imitations as his shooting. Then there was the inimitable way he could keep the ball at his feet with his back to goal, warding defenders away. Just five-foot-eight, Dalglish simply wouldnt be tackled until he was ready to lay the ball off to another red shirt.

Maybe the most thrilling sight, though, was when he got on his figurative bike with the ball and pedalled towards goal: supremely balanced, arms out at his sides as if ready for flight, surrounded by some sort of force field that could cause brawnier opponents to bounce off him like Derby Countys Vic Moreland who, first left for dead by a Dalglish turn, was then deposited on his backside as Dalglish shrugged him off and used his left peg to strike a rare power shot past the Derby keeper. The grin he showed us after that bravura effort was extra-radiant.

Dalglishs sunshine face, it should be said, was reserved only for such accomplishments. In football, the forwards facial expression is usually a weather vane for how his team is faring, and Dalglishs could be a grim sight if Liverpool happened to struggle. Evidently he hated to lose, so it was a good thing Liverpool didnt lose very often. Kevin Keegan had left the club having made them champions of Europe, but Dalglish had gone on to match that feat and by 1980 he seemed already, remarkably, to have eclipsed his predecessor. It wasnt just us little autograph hounds for whom Liverpool was Dalglish.

That night in Dublin the hunting pack of which I was part succeeded finally in cornering the great man, alone in a corridor as he emerged from his room, subdued, in a lemon-yellow V-neck sweater. (This was still the era before footballers were style icons who posed for billboard ads in little Armani pants.) Very probably hed been asleep his standard preparation for a game of any sort. We all knew from diligent study of Shoot! magazine that Dalglish was the consummate professional, a man of regular habits, a home-loving, teetotal non-smoker who prized his private peace and quiet above all else. Even so, regardless, we fell upon him, our books and scraps and pens thrust in front of his quizzical frown.