PROLOGUE

How the Man in Black

Became the Man in White

CITIZEN TWAIN

O N A BLUSTERY Friday afternoon in December 1906, Mark Twain arrived for a special appearance at the Library of Congress, trailing smoke from his usual brand of cheap cigar. The temperature hovered at freezing and the skies were gloomy, but he was dressed warmly in a long dark overcoat and a derby from which thick curls of white hair protruded on either side. At the main doors, facing the Capitol, he entered the Great Hall of the Library and made his way down a long marble corridor to the Senate Reading Room, where a hearing was in progress on copyright legislation. The Librarian of Congressa dapper middle-aged man named Herbert Putnamwas expecting him and emerged from the hearing to escort Twain inside.

All heads turned as the famous guest strode to the front of the chamber, which was full of lobbyists, lawyers, authors, and publishers. Normally used as a private study for senators, the high-ceilinged room had the look and feel of an elegant club, with oak paneling, mahogany desks, black leather chairs, and a big marble fireplace. At a long conference table facing the gathering were the dozen or so members of the Joint Congressional Committee on Patents, chaired by a jowly Republican lawyer from South Dakota, Senator Alfred Beard Kittredge.

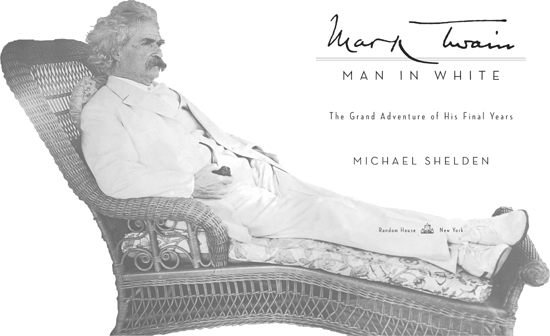

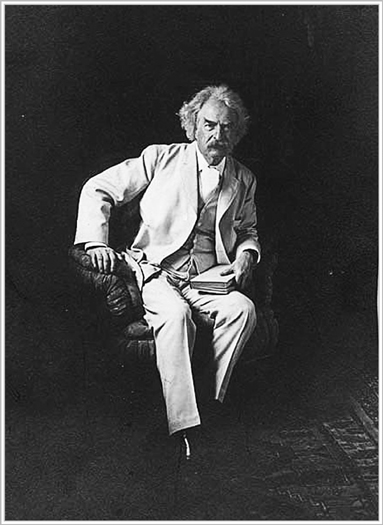

A representative of the player piano industry, a Mr. Low, was droning on about copyright protection for perforated music rollsMay I suggest an addition to clause (b) of section 1when Twain reached his seat and paused to remove his overcoat. By this simple gesture he causedas one observer later put ita perceptible stir. That was an understatement. Against the fading light of the afternoon Twain emerged as a figure clothed all in white. His outfit perfectly matched his hair, from his white collar and cravatheld in place by a creamy moonstoneto his white shoes. Among so many soberly dressed fellows in black and gray, he stood out as a gleaming apparition, impossible to ignore.

Mark Twain Bids Winter Defiance, said the headline in the New York Herald the next day. Resplendent in a White Flannel Suit, Author Creates a Sensation. The New York World called his costume the most remarkable suit of the season, and another paper said he was a vision from the equator who warmed the hearts of his audience while the wintry wind whistled around the dome of the Capitol. The best comment came from the Boston Herald: Oh, that all lobbyists could enter the congressional corridors in raiment as spotless as Mark Twains.

All day long, Senator Kittredge and his colleagues had been listening to various experts explain the fine points of the nations copyright laws, and much of the discussion had been dry and tedious. The committee members had grown restless and bored as they listened to yet another lobbyist argue his case with statistics and legal precedents. But the moment Twain removed his overcoat, the room came to life, and the legislators stared wide-eyed at the man in white as he waited his turn to speak.

Twains good friend and fellow novelist William Dean Howells, who was sitting nearby, was so taken aback by this unconventional outfit that the first words from his mouth were What in the world did he wear that white suit for? Appearing in such clothing at a formal gathering was a shocking breach of etiquette. In summer months, Washington was full of people in white suits, but in December nobody dared to dress that way.

Twains suit is now so famous that modern depictions of the author rarely show him in any other garb. The common assumption is that it was his signature look for much of his career. In fact, Senator Kittredges otherwise dull committee hearing marked not only the public debut of Twains uniform, but the beginning of an extraordinary period in which the authorwho had just turned seventy-onefashioned much of the image by which he is still known a century afterward.

He planned this debut carefully, and knew how the world would react. As a man who had spent years bedazzling audiences at lectures and banquets, he had a keen appreciation for the power of theatrical effects, and was sure that no one would forget the way he looked in white. Only two months earlier he had confessed privately, I hope to get together courage enough to wear white clothes all through the winter. It will be a great satisfaction to me to show off in this way. He wasnt ashamed to seek attention, explaining, The desire for fame is only the desire to be continuously conspicuous and attract attention and be talked about. Indeed, his debut in white provoked comment on front pages everywhere. For several days it was all anyone could talk about.

It wasnt by chance that he chose to reveal his new look in one of the most conspicuous places in Americathe nations greatest library. Though the building was only ten years old, it was already regarded as a monument for the ages. Built in the style of the Paris Opera House, it had the kind of splendor usually associated with great landmarks of the Old Worldwith soaring columns, grand arches, and a massive dome. Admirers boasted that it was the largest, the costliest, and the safest library in the world. For a literary man wanting to stage a sensational event, there wasnt a better backdrop.

Though the extensive press coverage pleased him, Twain wasnt merely showing off. He had serious business to conduct at the hearing, where he wanted to urge legislators to change the system of copyright law, which he considered archaic and unjust. It was a subject close to his heart. For years he had been fighting to improve the system, but now he regarded the problem with a greater sense of urgency. His long career was nearing its end, and the future of his lifes work was at stake.

When he stood up to speak, he knew that he would command complete attention. Like a good showman, he understood that his words would seem all the more impressive coming after so many lackluster speeches by ordinary men in conventional attire. For almost half an hour, he held the floor, addressing the room directly instead of speaking only to the legislators. Though he had composed a few rough notes earlier in the afternoon, he didnt bother to refer to them. He preferred to speak from the heart, and did so without hesitation, employing sound reasoning and amusing anecdotes, and making an occasional sardonic swipe at the glacial pace of reform. His real audience was not the men in the room, but the larger American public who would read of his appearance in their newspapers the next day.

![Twain Mark - Autobiography of Mark Twain Vol. 1 / associate eds. Benjamin Griffin ... [et al.]](/uploads/posts/book/210276/thumbs/twain-mark-autobiography-of-mark-twain-vol-1.jpg)