SURELY THE NEWS GAVE the old man a feeling of redemption as well as pride. Gnarled and decrepit at eighty-nine years of age, but still sharp of mind, John Adams learned on February 14, 1825, that his eldest son, John Quincy, would become the sixth president of the United States.

Nearly a quarter of a century had passed since Adams had bitterly yielded the presidency to Thomas Jefferson, his revolutionary protg turned political rival, when the election of 1800 saw candidates from opposing political parties contend for the office for the first time. On March 4, 1801, in the waning hours of his single White House term, the second president, and the last Federalist to hold the office, stole away from Washington rather than bear witness to the noon inauguration of Jefferson, the founder of the Democratic-Republican Party and, effectively, the first Republican. Under the light of a crescent moon, Adams boarded a 4:00 a.m. stagecoach bound for Baltimore on the first leg of a five-day, 450-mile journey that would take him back to his native Quincy, Massachusetts, and into political exile.

It took just as longfive daysfor word of his sons election to reach Adams in Quincy. The news had been considerably longer in the making. It had taken over three months for the outcome of the election of 1824 to be decided. At a time of growing factionalism, the Democratic-Republican Party, the only political party during the time from 1801 to 1825, put up four presidential candidates representing regional distinctions: John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts, Andrew Jackson of Tennessee, William Crawford of Georgia, and Henry Clay of Kentucky. While Andrew Jackson had handily won the popular vote41 percent overallhe lacked the majority of electoral votes needed to win the office. The presidency hung in the balance.

The victor would be determined by the U.S. House of Representatives in a runoff vote of the three top candidates: Adams, Jackson, and Crawford. But it was the fourth candidate, Henry Clay, who controversially put the matter to rest by convincing his supporters to pledge their electoral votes to the candidate from Massachusetts; Adams emerged as the winner. In return, Clay exacted assurances that he would be appointed Adamss secretary of state and thus, by historical proclivity in those years, the presidential heir apparent.

The elder Adams considered his sons ascent to the countrys highest office to be one of the most fulfilling moments of his long life. Among the congratulations he received was a warm letter from Jefferson, whose enmity, along with Adamss, had long ago faded with the recession of political passions and the burnishing of their intertwining legacies as essential founding fathers. The third president wrote from Monticello: It must excite ineffable feelings in the breast of a father to have lived to see a son to whose educ[atio]n and happiness has been so devotedly so eminently distinguished by the voice of his country.

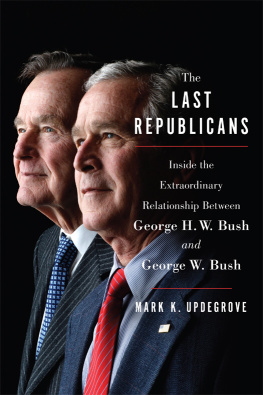

One hundred and seventy-six years would pass before the son of another president would become the nations commander in chief. George Herbert Walker Bushs feelings of pride in his son George Walker Bushs ascent to the presidency at the dawn of the twenty-first century undoubtedly stirred in his breast just as deeply as had Adamss for his own son. It was all about family loyalty and pride for a father in his son, Bush reflected later. But like Adams, he may have felt in it some absolution. After a life devoted largely to public service, Bush had climbed the ranks of the Republican Party through elections and appointments, serving as vice president to Ronald Reagan for two terms before succeeding him and becoming the first incumbent vice president to be elected to the presidency since Martin Van Buren had done it in 1836, over a century and a half earlier.

Bush skillfully presided over a peaceful end to the Cold War, reunited Germany despite European resistance, and established an unprecedented international coalition around the liberation of Kuwait from Iraqi forces in the Gulf War. But his waterloo came on the domestic front when he broke a no new taxes campaign pledge to facilitate a 1990 budget deal while conservatives, always wary of Bush as a closet moderate, cried foul. He left the White House unseated by his Democratic challenger, Bill Clinton, after a single term. Though Bush handled defeat with graciousness that eluded the irascible Adams, he left Washington with an unfinished agenda and an ambiguous legacy, a disappointment Adams would not have found unfamiliar.

Just as the fathers stood on common ground, there were similarities in circumstance between their oldest sons. Like John Quincy Adamss, George W. Bushs election had come hard. After a mutable election night grounded in uncertainty, Bushs contest against Democratic challenger Al Gore came down to the state of Florida, where voting irregularities held up the final results. Gore had won the popular vote nationwide, but Florida would give either candidate the necessary electoral votes to swing the election overall. It fell to the U.S. Supreme Court to resolve the dispute. In a divisive judgment reminiscent of the vote rendered by the U.S. House of Representatives in 1825, the high court made its ruling in Bush v. Gore on December 12, 2000, a month and five days after the election: George W. Bush would be going to the White House.

So, in effect, would his father.

Few fathers have lived to see their sons become president. It had happened only twice in the twentieth century: Calvin Coolidge Sr., a modestly successful politician and businessmanand a notary publicswore his son into office at his home in Plymouth, Vermont, in 1923, after Vice President Calvin Coolidge Jr. assumed the presidency upon the death of Warren Harding. Thirty-seven years later, in 1960, Joseph Kennedys wealth and power were instrumental in propelling his son Jack into the White House. After an earlier race for the U.S. Senate, the younger Kennedy joked that his father had sent a wire instructing him to buy no more votes than necessary. Ill be damned if Im going to pay for a landslide. When John F. Kennedy won the presidency in a squeaker, he realized not only his own ambitions, but also those of the imperious Kennedy patriarch. Coolidge Sr. died in 1926, midway through his sons tenure as president, and the elder Kennedy suffered a massive stroke less than a year into his own sons presidency, rendering him partially paralyzed and unable to speak. Regardless, whatever paternal guidance they could offer their sons in their journeys at the nations helm, neither had been there before them.

Bush had been there. And unlike John Adams, who died in Quincy (providentially on July 4, 1826), having seen his son only once for a few short days in Quincy during the course of the latters presidency, Bush was readily accessible to his son in a communications age the Adamses could only have imagined. Twenty-four years had elapsed between the Adams presidencies, but only eight years separated the Bushes terms in officeinterrupted only by Clintons administrationand the elder Bush, a nimble seventy-six upon his sons 2001 inauguration, could be there for him.

And he was there: not only in the White House, where he spent many nights during his sons tenure and where much of the staff had remained unchanged since his presidency, but also at Camp David, the presidential mountain retreat, on his sons Texas ranch outside Waco, and at the Bush family compound in Kennebunkport, Maine. When he wasnt there physically, he could be on the other end of the phone whenever the president called. He could provide not only succor but also the counsel of one who knew firsthand the burden his son carried. Father and son would come to refer to themselves numerically as 41 and 43, a nod to their places in the presidential continuum and to their mutual attainment.