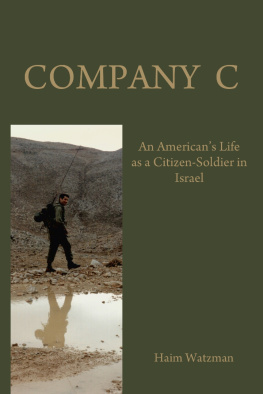

COMPANY C

COMPANY C

COMPANY C

COMPANY C

An Americans Life as a Citizen-Soldier in Israel

Haim Watzman

Copyright 2005 by Haim Watzman

All rights reserved

This book may not be reproduced in whole or in part, by mimeograph or any other means, without permission. For information, address Writers House LLC at 21 West 26th Street, New York, NY 10010.

Grateful acknowledgment is made to the following for permission to reprint previously published material:

What to Do When Surrounded, copyright 2003 by David Wagoner. Used by permission of the author.

Odysseuss Secret, from Different Hours by Stephen Dunn. Copyright 2000 by Stephen Dunn. Used by permission from W. W. Norton and Company, Inc.

Some names have been changed.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Watzman, Haim.

Company C : an Americans life as a citizen-soldier in Israel / Haim Watzman.

p. cm.

ISBN-13: 978-0-7867-5355-0

1. Watzman, Haim. 2. AmericansIsraelBiography. 3. IsraelArmed ForcesReservesBiography. 4. Arab-Israeli conflictAnecdotes. 5. Arab-Israeli conflictMoral and ethical aspectsIsrael. I. Title.

DS113.8.A4W37 2005

956.9405'092dc22

2004006578

Distributed by Argo Navis Author Services.

For Ilana, with all my love

A man finds his shipwrecks,

tells himself the necessary stories.

STEPHEN DUNN, ODYSSEUSS SECRET

CONTENTS

COMPANY C

COMPANY C

A KHAKI-COLORED CANVAS BAG SLUMPS BEHIND THE FILING CABINET in the tiny basement storeroom that doubles as my study. It bears faded Hebrew letteringmy name and serial numberand inside is a pair of black army boots, a set of work fatigues, and a hat. Theres a battered pocket-sized prayer book, a pen and notepad, and sand from the Negev desert, from Hebron and Jenin in the West Bank, from Mt. Hermon, and from Lebanon.

In army slang its called a chimidan, a word that, like so many others in the peculiar argot of this most Israeli of institutions, comes from another languagein this case, the authorities say, from Tatar, by way of Russian. After twenty years of intensive use, my chimidan is still strong. The canvas handles have withstood the weight of thick novels and extra ammunition, and the heavy-duty zipper has survived the strain of chronic overstuffing. It could be used for camping trips or family vacations, since I no longer need it for the army. But I havent had the heart to unpack it. Too much history, too many memories, too much of my biography is in there. It just wont do for anything else.

Owl-necked looking back / to where you might have been / or what you could have done /... you cant believe this skintight is your skin, says Sharon Dolin, in a poem called Regret that I have pasted on my door. Memories are tricky; they dont really tell us what was, but rather what was through the scrim of what happened after. But Im pretty sure that no one who knew me in high school would have predicted that in middle age Id be sitting down to write about my military career. Not that bookish kid, so physically inept that any team forced to take him in gym class got two extra players as compensation. I am the antithesis of a warrior. I cant throw a grenade far enough to keep myself alive. I never use bad language, and I daydream under pressure. Yet for twenty years of my life I was a soldier. I was a soldier as I adjusted to a new country, as I sought and found love, as I raised my children, as I pursued my career. At times I patrolled and defended my countrys borders; at other times I served beyond them, or in that gray area, the occupied territories, the West Bank and Gaza Strip. I served in uniform in conflicts that I demonstrated against in civilian clothes.

I never planned to or particularly wanted to join an army. No romantic images of heroic fighters were instilled in me when I was young. There was no family military tradition to speak of. My paternal grandfather, apparently the first Watzman in untold generations to bear arms, was drafted into the czars army in 1914 and deserted at the first opportunity. My father served honorably as a rifleman in the U.S. army at the tail end of World War II, but he did not speak of this much when I was a boy and certainly never expressed any hope that I would follow in his footsteps.

In the 1960s, the years of my childhood, middle-class Jewish boys were not inculcated with a sense of military duty. The army was just not something we did. As the Vietnam War escalated, military service became first something one avoided, and then, as political opposition to the war burgeoned, something one criticized, even despised. This was certainly not World War II, when my father eagerly awaited his eighteenth birthday so he could join the fight against Hitler. Hitler had been a clear and immediate threat both to the Jewish people and to the United States. The Viet Cong were not, as far as my friends and I could make out.

Israels warsspecifically the Six-Day War of 1967, which broke out when I was at the end of sixth grade, and the Yom Kippur War of 1973, which erupted at the beginning of my senior year in high schoolseemed different. I wasnt one of those guys with romantic ideas about heroic Israeli citizen-soldiers battling evil Arabs, though some of my friends were, and aspired to go to Israel to become such men. But even without the romance, service in the Israeli army looked different. Israeli soldiers were defending their homes and families, not serving as pawns in a geopolitical game. And their cause, protecting the Jewish state from enemies who sought to destroy it, seemed just beyond dispute. Yet I felt no particular obligation to enlist in that cause. My family and friends were in America, and I had no thought of living elsewhere.

Unlike many of my Jewish friends at my high school in suburban Washington, I did not join one of the several Zionist youth movements that had active local chapters. Perhaps I would have, had someone invited me. But, at least in early adolescence, when those cliques formed, I didnt fit in well. Anyway, Zionism didnt fire me up the way it did others. Of course I was a Zionistwerent all the Jews I knew? It went without saying that I supported the state of Israel. In my family, however, Zionism was but one of many aspects of our Jewish identity. Unlike the parents of one high school friend, my own parents had never tried to settle in Israel. Unlike some other classmates, I had no relatives there. Most of my friends went on summer trips to Israel with their youth groups. I did not.

Given my personality, its not surprising that the part of Judaism that caught my attention was not Israel but books. At a communitywide after-school program for Jewish teens, I became aware of a vast corpus of Jewish textsthe Bible, commentaries, Talmud, Midrashwith which the Jews I knew seemed to have little acquaintance. Most of the teachers in this program were Orthodox, and I was surprised and intrigued to discover that the stereotype I had of religious Jewsdogmatic, rigid, afraid of new ideasdid not fit them. True, they were strictly observantmuch more strictly than I could ever imagine myself being. But they liked nothing more than a lively argument. They seemed willing to entertain, dissect, analyze, and dispute any notion or idea my classmates and I could throw at them, no matter how hereticaleven if, at the end of the discussion, they stuck to their Orthodox guns. I soon came to realize that this love of a good argument, and the keen talent for turning every proposition over every which waystripping it of cant and emotion, and measuring its strengths and weaknesseswas rooted in the rabbinical texts that we studied. There was a lot more intellectual energy in Maimonides and the Talmud than in the bland American synagogue Judaism with which Id grown up.

Next page

COMPANY C

COMPANY C