The Secret Life of Plays

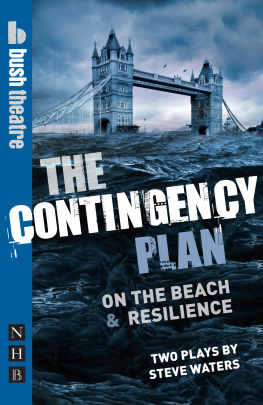

Steve Waters

NICK HERN BOOKS

London

www.nickhernbooks.co.uk

For Hero, Joseph and Miriam

Acknowledgements

The author and publisher gratefully acknowledge permission to quote from the following:

Attempts on her Life (1997), The Country (2000), The Treatment (1993) by Martin Crimp; Translations by Brian Friel (1981); Observe the Sons of Ulster Marching Towards the Somme by Frank McGuinness (1986); The Birthday Party (1960), The Caretaker (1961), Old Times (1971) by Harold Pinter; all published by Faber and Faber Ltd.

Lear (1972), Saved (1966) by Edward Bond; Mother Courage and Her Children by Bertolt Brecht, translated by John Willett (1980); Top Girls by Caryl Churchill (1982); Copenhagen by Michael Frayn (1998); Across Oka by Robert Holman (1988); Cleansed (1998), Crave (2001) by Sarah Kane; Edmond (1983), Glengarry Glen Ross (1984), Oleanna (1993) by David Mamet; The Wonderful World of Dissocia by Anthony Neilson (2007); Handbag by Mark Ravenhill (1998); all published by Methuen Drama, an imprint of A&C Black Publishers Ltd.

Woyzeck by Georg Bchner, translated by Gregory Motton (1991); Apologia by Alexi Kaye Campbell (2009); The Cherry Orchard by Anton Chekhov, translated by Stephen Mulrine (1998); Far Away by Caryl Churchill (2000); Conversations with Pinter by Mel Gussow (1995); all published by Nick Hern Books Ltd.

Every effort has been made to contact copyright holders. The publisher will be glad to make good in any future editions any errors or omissions brought to their attention.

Writing this book has made me very aware of the many people to whom I am indebted in terms of my own education in playwriting. I would like to mention with thanks a few of them here, beginning with Professors Valentine Cunningham and Thomas Docherty, and Susan Hitch, who shaped my thinking on so many aspects of this book; to David Edgar himself, without whom it would simply have been an unthinkable project; to the late Clare McIntyre, who taught me the instinctual aspect of the craft and to the also much-missed Sarah Kane, who taught me to rethink everything I thought I had learned hitherto; to my former colleagues at Homerton College, Cambridge, especially Dr Helen Nicholson and Dr Peter Raby, who inducted me into scholarship as an art form; to my friend Ian Smith, whose company and theatrical awareness has informed my own thinking in a multitude of ways; to my former teaching colleagues in numerous schools and especially Simon Veness, who bore the brunt of my very partial theatrical awareness, and to my current colleagues at the University of Birmingham who continue to do so. But most critical of all, to all of those who have been my students across the years in schools, FE colleges, as undergraduates and post-graduates, who have kept the learning alive and vital, and all my comrades as writers and directors in the theatre, and our conversations over the years which have been ruthlessly pillaged here in particular to Josie Rourke, and my agent and friend Micheline Steinberg. Finally, a debt of love and gratitude is owed to my wife Hero Chalmers, who has encouraged and supported me throughout this project and whose own sharp thinking has been crucial to the outcome; and to my children Joseph and Miriam, who are a daily inspiration.

Last of all I would like to express enormous thanks to my editors at Nick Hern Books and especially to the assiduous and meticulous Robin Booth who has been the kindest and most patient midwife any embryonic author could hope for.

Steve Waters

Introduction

Inside the Apple

The author is the worm at the core of the apple

Samuel Beckett

There is something mysterious in the effect and impact of a good play, something that might originate in the intentions of an author, but which soon outstrips them.

As a playwright myself, I recognise the truth of Becketts image of the place of the author in the act of writing. I have been that worm in the apple, excavating my plays from within. My working process is less that of a sculptor, looming over their block of stone in a posture of mastery, and more akin to a miner working their way out from within the rock, hoping to bring some precious metal to light. Plays remain stubbornly paradoxical at their core, beginning as dreams and ending as public documents, as full of space and silence as they are of words and intention.

Most mysterious of all is the very source of a play, the authors intuitive creativity, which resides encrypted in what T.S. Eliot called the dark embryo. If a play doesnt have an umbilical cord feeding into that dark embryo, itll be dead on arrival. And sounding out such sources is unwise. Seamus Heaney characterises the moment of inspiration as being like putting your hand into a nest and finding something beginning to hatch out in your head. What hatches out in the head, not what lurks in the nest, is the concern of this book.

If I begin by recognising the mysteries ahead, its because all too often writing about playwriting and drama boils down to offering an inventory of conventions, as if plays were no more than the sum of their parts. This approach resembles the attempts of phrenologists to detect a felon from the shape of their skull. In this respect the father of all such commentaries, Aristotle, is culpable in effect, if not intent: how many generations of playwrights and critics have rummaged through the checklist of elements in his Poetics, hoping to find there a ready-made framework for their plays? Its all too tempting. Technical terms, especially Greek ones, sound very authoritative: take some dianoia, add in a little sophrosyne, sprinkle over it a smidgeon of anagnorisis, work the whole lot into a lovely peripeteia, and wait for the inevitable katharsis. It would be unfair to blame this reductiveness on Aristotle alone, whose text was probably a set of lecture notes rather than a more considered work. Nevertheless, his crib set the discussion going and its approach is still mirrored in what there is of playwriting pedagogy today.

Another shortcoming of Aristotles account of the heyday of Greek theatre is its relentless focus on Sophocles Oedipus Tyrannus. Yes, its a very good play, no question, but this poster-boy of formal perfection has too often served as a cudgel to beat into shape all sorts of equally good but formally eccentric works. How would Aristotles toolkit of unities have served him had he considered the unruly danger of Euripides The Bacchae or the trilogy of The Oresteia, let alone the madcap playfulness of Aristophanes? The fact that it stakes everything on one exemplary text perhaps explains the seductive reductiveness of the Poetics.

Aristotle was primarily a philosopher, and philosophers tend to make dogmatic critics, veering to the prescriptive, dismembering plays to illustrate their concepts. Anyone who has battled with Hegels writings on tragedy can testify to how theory even magnificent theory tends to pare the biodiversity of actual plays back to a monoculture of well-behaved exemplars. Nevertheless, however much we might crave papyrus records of Aeschylus in a post-show discussion, or Euripides unpublished essays Writing in Tavernas, Aristotles end-of-term report still sets the standard.