BY GEORGE VECSEY

Baseball: A History of Americas Favorite Game

Forever Yours, Faithfully (by Lorrie Morgan)

Troublemaker (by Harry Wu)

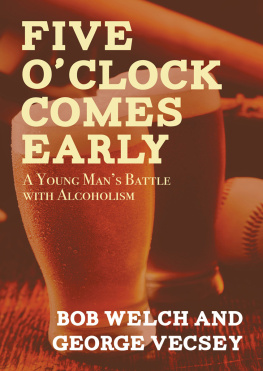

Five OClock Comes Early: A Young Mans Battle With Alcoholism

(by Bob Welch)

Get to the Heart (by Barbara Mandrell)

A Year in the Sun

Martina (by Martina Navratilova)

Sweet Dreams (with Leonore Fleischer)

Kentucky: A Celebration of American Life (with Jacques Lowe)

Getting Off the Ground: The Pioneers of Aviation Speak for Themselves

(with George C. Dade)

Coal Miners Daughter (by Loretta Lynn)

One Sunset a Week: The Story of a Coal Miner

The Way It Was: Great Sports Events from the Past (Editor)

Joy in Mudville: Being a Complete Account of the Unparalleled History

of the New York Mets

Naked Came the Stranger (1/25th authorship) (Lyle Stuart, 1969)

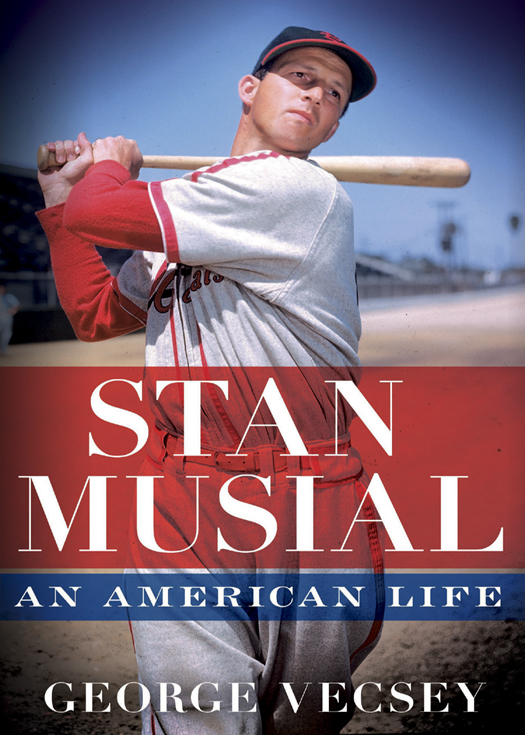

Stan Musial: An American Life

CHILDRENS BOOKS :

Frazer/Ali

The Bermuda Triangle: Fact or Fiction? (with Marianne Vecsey)

The Harlem Globetrotters

Pro Basketball Champions

Photographer with the Green Bay Packers (with John Biever)

The Baseball Life of Sandy Koufax

Baseballs Most Valuable Players

Copyright 2011 by George Vecsey

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by ESPN Books, an imprint of ESPN, Inc., New York, and Ballantine Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York.

BALLANTINE and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

The ESPN Books name and logo are registered trademarks of ESPN, Inc.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Vecsey, George.

Stan Musial: an American life / George Vecsey.

p. cm.

eISBN: 978-0-345-52644-1

1. Musial, Stan, 1920 2. Baseball playersUnited StatesBiography. 3. St. Louis Cardinals (Baseball team)History. I. Title.

GV865.M8V47 2011

796.357092dc22 [B] 2011003271

www.ballantinebooks.com

www.espnbooks.com

Front-jacket photograph: Hulton Archive/Getty Images

Jacket design: Scott Biel

v3.1_r1

TO THE MUSIAL FAMILY

WITH ADMIRATION

Contents

Prologue

MORNING IN FLORIDA

W E DROVE straight through the night, married only a few months, on spring break, our first vacation together. Like Bonnie and Clyde, we had the feeling of putting something over on everybody. Every mile we traveled south of Baltimore was the farthest I had ever been from New York. We were twenty-one.

We arrived in St. Petersburg just after dawn on a Sunday, nothing much moving but the pelicans down by the bay. It was much too early to locate our friends, so we had a few hours to kill.

I happened to find the ballpark.

I had known about Al Lang Field since I was young, hearing Mel Allen describe DiMaggio and Henrich taking their first rips of the spring, the waves, and the sailboats on Tampa Bay.

The Yankees shared this homey little ballpark with the Cardinals, a team I had followed since I was seven years old, back in 1946. It was a wonderful year for the game, even though the Cardinals beat our beloved Brooklyn Dodgers in a playoff.

As that epic World Series began, my father, who worked at the Associated Press, brought home a full set of photographsglossies, they called themof all the players: one head shot and one posed action shot of all thirty Cardinals and Red Sox. (The rosters were expanded that year to make room for the veteransthe rusty, the wounded, and the aged.)

Mesmerized by the glossies, I would make lineups out of them, scrutinize the faces of the hard-boiled players who had known war and the Depression and the struggle to get to the major leagues.

I can remember the studious glint of Bostons Dominic DiMaggio, who wore glasses, and the exuberance of the Cardinals Joe Garagiola, who already had a reputation as a clubhouse character. But the player I liked best was Stan Musial, the lithe slugger of the Cardinals, just back from the war, who always seemed to be smiling as he went about his business of smiting terror in Brooklyn. Stan the Man, as we had named him, seemed to represent all the daily goodness of his sportthe workaday regularity, the possibilities, the joy.

Now, fourteen years later, I was a young sportswriter who had covered a few Yankee games, Casey and Mantle, the year before. I was old enough to be married, to be parked outside Al Lang Field, noticing a few cars arriving, men disappearing through the clubhouse door, with the quiet diligence of Depression-era workers grateful to be punching the time clock for another paycheck.

From the rearview mirror, I spotted two men strolling down the sidewalk, each carrying a bat. Why, it was Stan Musial and Red Schoendienst, old friends reunited after Schoendiensts four-year exile in New York and Milwaukee. They seemed as comfortable as matching salt and pepper shakers, wearing nice slacks and collared shirts, most likely just having come from church.

They walked past my car, not noticing the grimy clunker with New York plates that had gotten us out of the frozen North. Up close, I spotted Schoendiensts freckled catlike features and Musials vaguely lopsided smile, straight off the glossies I had studied years earlier. They were strolling to another March Sunday at the ballpark.

My pretty, young wife professed not to mind when I woke her up to point out the two ballplayers. Look, I babbled, its Stan and Red. I tried to explain about Musials coiled batting stance, how he could run, how we had loved him in Brooklyn, how he was the most beloved man in his sport. She humored me. We had driven through the night and had found the heart of baseball.

THE DO-OVER

B UD SELIG could see it coming. He did not know exactly which great player was going to be overlooked by the capricious impulses of baseball fans, but he was certain it was going to be somebody he loved.

The commissioner had brought this agony on himself by approving a commercial gimmick he suspected might backfire. A credit card company, a major sponsor, would arrange for fans to select the top twenty-five players of the twentieth century, using computerized punch cards. The winners would be announced during the World Series of 1999.

The drawback, and Selig knew it right away, was that this election could produce an injustice for some great players who had concluded their careers before the current generation of fans, before cable television began displaying endless loops of home runs by sluggers who were mysteriously growing burlier by the hour.

In addition to being the commissioner, with all the crass business decisions that post entails, Selig is a legitimate fan who grew up in Milwaukee, whose mother took him to Chicago and New York, giving him a lifelong appreciation for the game.

Knowing, just knowing, that some great players would be left out by mathematical inevitability, Selig did the prudent, fretting, consensual, quintessential Bud Selig thing: he arranged for an oversight committee that would add five players, making it a top-thirty team. He just knew.

Seligs premonition came true when voting closed on September 10, 1999. Pete Rose, who had been banned from baseball after blatantly denying he had gambled on games, was among the top nine outfielders on the all-century team; Stan Musial, with his perfect image, who ranked among the top ten hitters who ever played, was mired at eleventh. Stan the Man, an also-ran.