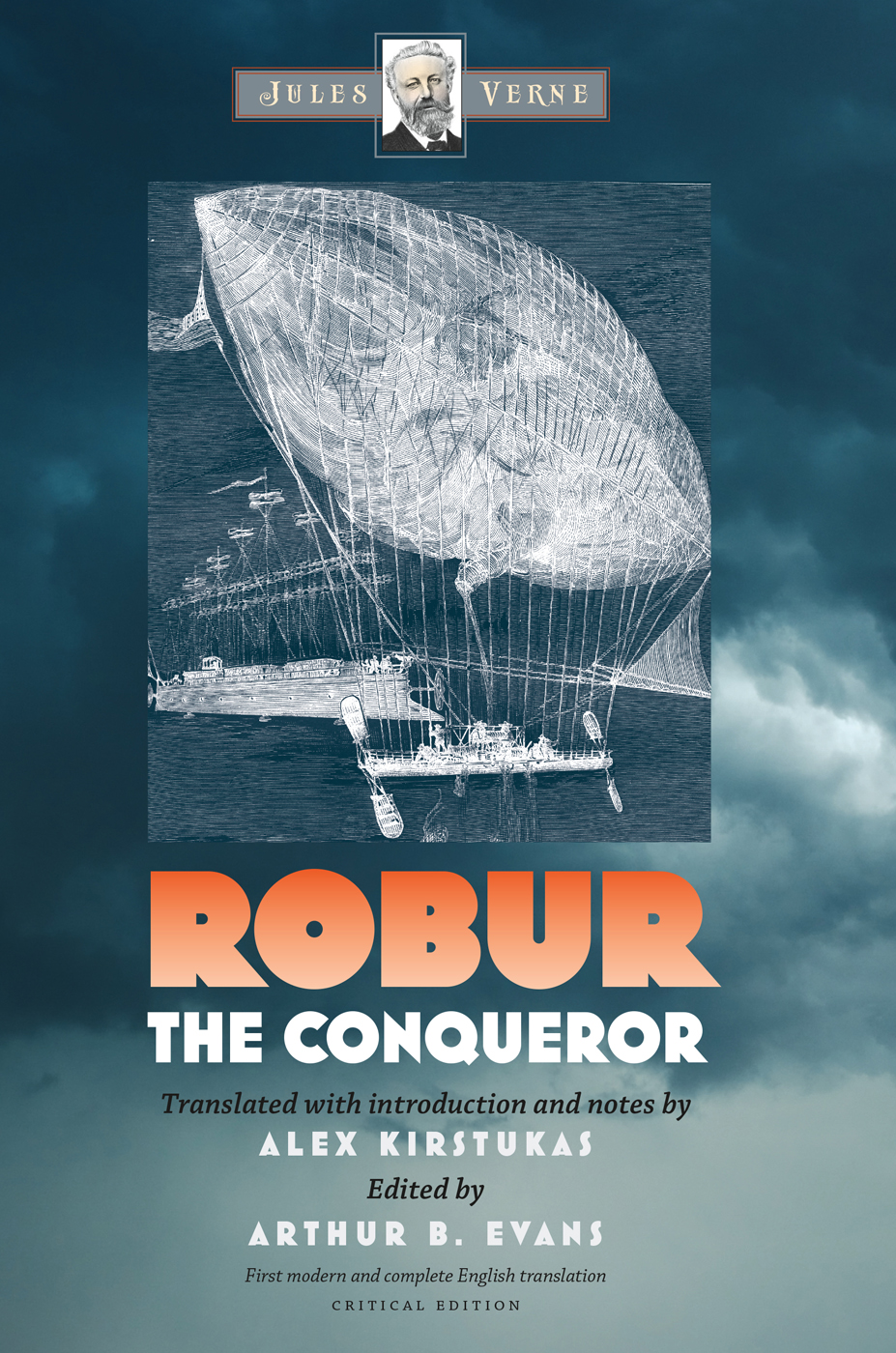

Robur

THE CONQUEROR

ROBUR

THE CONQUEROR

Jules Verne

Translated with introduction

and notes by Alex Kirstukas

Edited by Arthur B. Evans

First modern and complete English translation

WESLEYAN UNIVERSITY PRESS

Middletown, Connecticut

Wesleyan University Press

Middletown CT 06459

www.wesleyan.edu/wespress

Translation, introduction, and annotations 2017 Alex Kirstukas

Bibliography and biography 2017 Arthur B. Evans

All rights reserved

Manufactured in the United States of America

Designed by Richard Hendel

Typeset in Miller and Egiziano by Tseng Information Systems, Inc.

Hardcover ISBN: 978-0-8195-7726-9

Ebook ISBN: 978-0-8195-7728-3

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data available on request

5 4 3 2 1

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

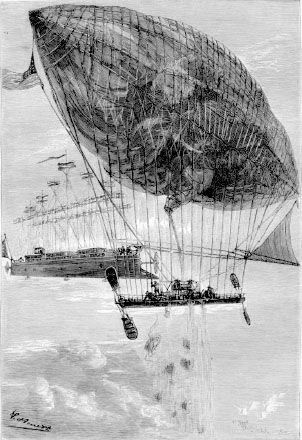

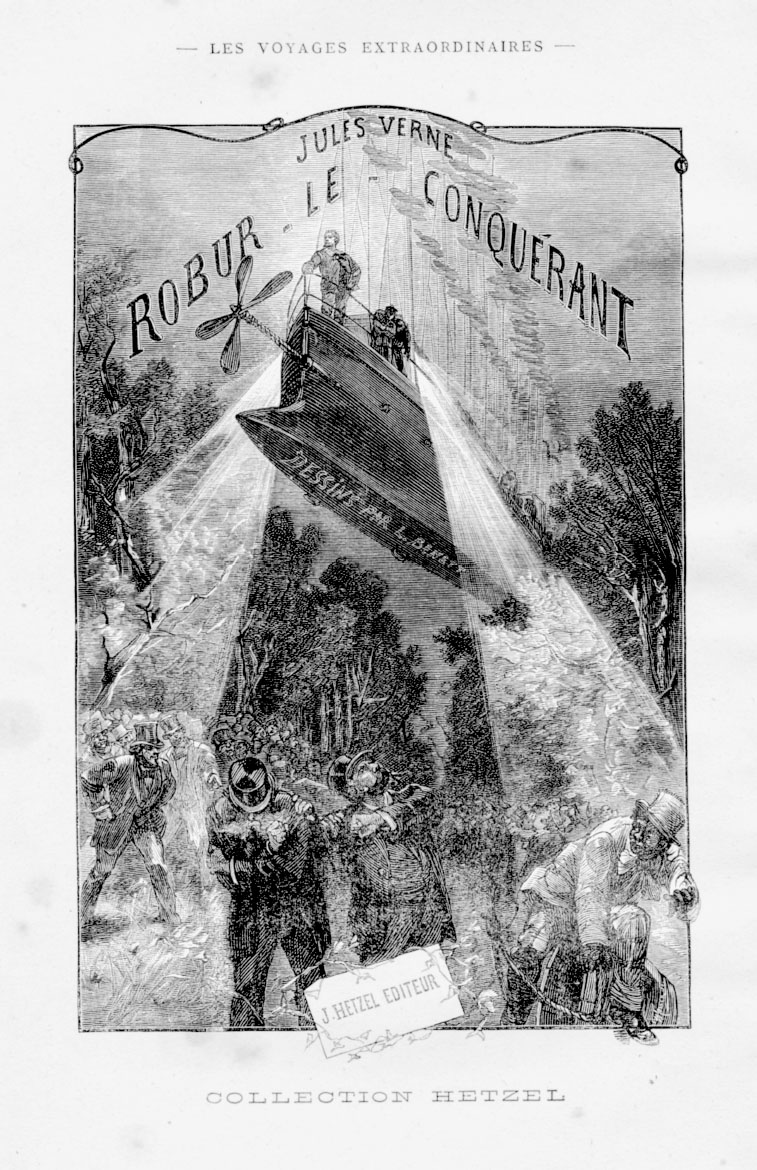

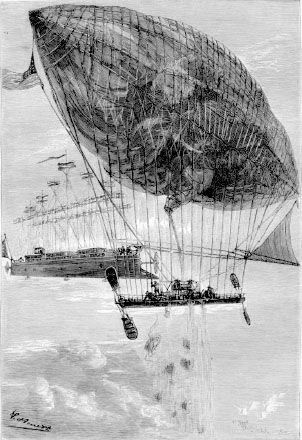

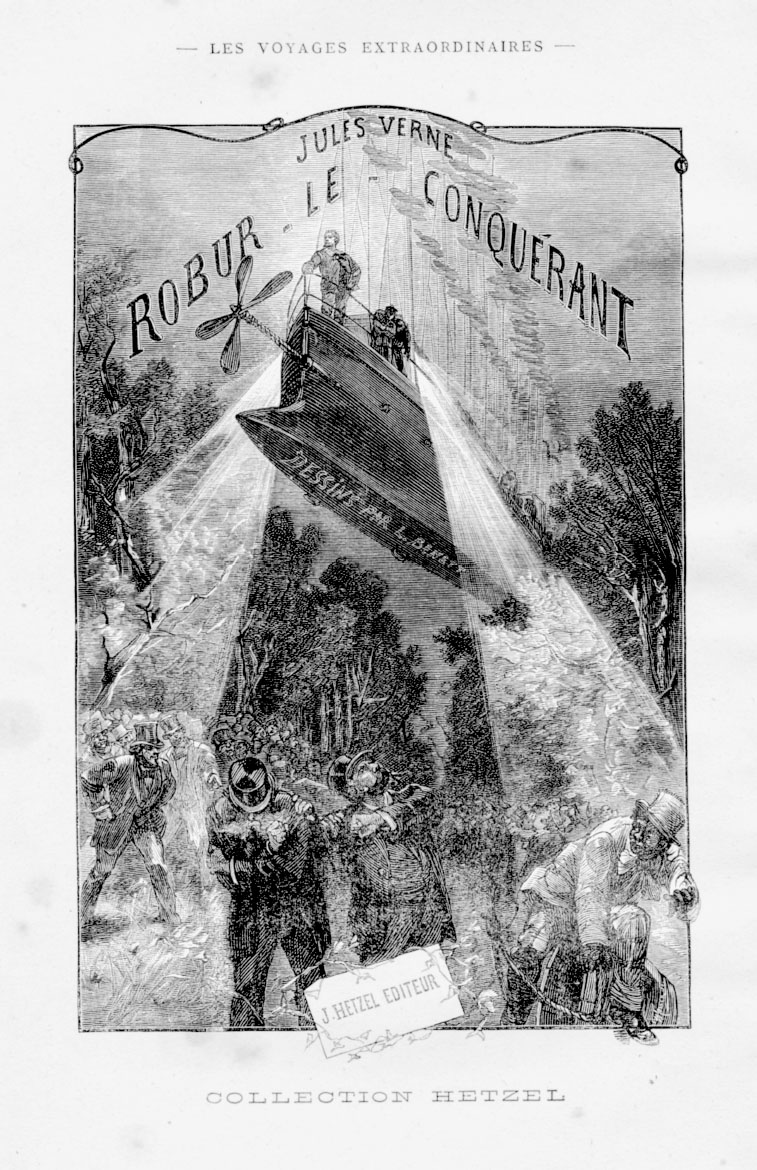

When Jules Verne takes to the air, we have every reason to anticipate something special. Robur-le-conqurant (Robur the Conqueror, 1886) is one of the phenomenally influential French novelists most iconic works, with its enigmatic central figure and especially its magnificent imaginary aircraft, the Albatross. Though the novel took its impetus from a now-obscure debate that pitted lighter-against heavier-than-air flight technology, it still thrills and perplexes in equal measure. Much ink has been spilled over the books faults, merits, and multiple themes, but this much is immediately clear: it is a playful, argumentative, often compellingly ambiguous explorationfrom the distant past to what was then the near futureof humankinds quest to conquer the sky.

France had been deeply interested in flight since 1783, when aeronautical history was made twice: the brothers Joseph-Michel (17401810) and Jacques-tienne Montgolfier (17451799) developed the hot-air balloon or Montgolfire, and Jacques Charles (17461823) invented the gas balloon or Charlire. Balloon mania swept France, continuing unabated through the mid-nineteenth century.

But could a balloon be controlled? Verne, then an unknown twenty-three-year-old writer, implied doubts about that possibility in his second published story, Un Voyage en ballon (A Voyage in a Balloon, 1851), where a character who claims to have invented a steering mechanism is quickly revealed to be insane. So speaks Samuel Fergusson, hero of Vernes first published novel, Cinq semaines en ballon (Five Weeks in a Balloon). With this books publication in January 1863, Verne began his legendary collaboration with the publisher Pierre-Jules Hetzel (18141886), launching a series of grippingly plotted and abundantly well-researched novels that would soon be collectively titled the Voyages extraordinaires (Extraordinary Voyages).

As both the short story and the novel suggest, Vernes interest in balloons was complex. On the one hand, his fascination with the mysterious and the wondroushis Romantic side, with a capital Rmade him as excited as anybody about the possibilities of flight. On the other, his equally strong pull toward the rational and the scientific led him to realize that balloons could not, and probably would never be able to, live up to the idealized expectations being set for them.

Verne was not alone. Just a few months after Five Weeks was published, three people equally excited about the boundless potential of flight, and equally convinced about the impracticality of balloons, joined forces to advocate for other means to the sky. The viscount Gustave de Ponton dAmcourt (18251888) and the writer Gabriel de La Landelle (18121886) believed the future belonged to heavier-than-air flying machines driven by propellers; the two of them coined the words hlicoptre and aviation, respectively. On July 6, 1863, they teamed up officially with the polymathic photographer-journalist-balloonist-showman Gaspard-Flix Tournachon (18201910), known as Nadar, to launch a Socit dencouragement pour la locomotion arienne au moyen dappareils plus lourds que lair (Society for the Encouragement of Aerial Locomotion by Means of Heavier-Than-Air Machines). Verne, one of the earliest to join, was made one of the finance directors. He fulfilled the post diligently and came regularly to meetings.

Nadar, a dyed-in-the-wool rabblerouser, went into high gear to promote the Society and popularize his colleagues plans for proto-helicopters. First he published an iconoclastic Manifeste de lAuto-locomotion arienne (Manifesto of Aerial Autolocomotion, La Presse, August 7, 1863), casting heavier-than-air researchers as underdog heroes fighting a pompous, pretentious establishment obsessed with balloons. The battle imagery caught on; soon, inspired by a joke from the Manifesto, journalists were referring to Nadar and his colleagues as les chevaliers de La Sainte Hlice (the Knights of the Holy Propeller). Nadar continued the publicity blitz by launching the illustrated magazine LAronaute, complete with cover art by the eminent Gustave Dor. In the most memorable publicity stunt of all, Nadar raised funds for aircraft experimentation by commissioning the largest balloon ever built, the Gant, and gathering audiences to watch his ascensions in it, just as professional aeronauts were doing all over Europe. The Society was soon swarming with scientists, researchers, writers, and musicians, everyone from George Sand to Jacques Offenbach. In December 1863, Verne did his own part to raise publicity for the work, pointing out the advantages of helicopters and the drawbacks of balloons in the short essay propos du Gant (About the Gant).

But the Society produced no workable results in its few years of activity, and after a brief flare of interest, flying machines faded from the popular imagination. Balloons served heroically during the Siege of Paris in 187071, carrying mail and people over the entrapped city walls. Nadar himself was a leading player in the heroics.

But Verne was not finished with the heavier-than-air aspirations of the 1860s. He nearly wrote an aircraft into the Extraordinary Voyages in 1875, when he planned to gather the heroes of his previous booksSamuel Fergusson, Pierre Aronnax, Phileas Fogg, and so forthand send them on an aerial trip around the world.

Two years later, flight returned to the news. On August 9, 1884, the French captains Charles Renard (18471905) and Arthur Krebs (18501935) flew twenty-three minutes in an electric dirigible, La France. The flight was an obvious and celebrated successso much so that the polymathic aeronautical brothers Gaston (18431899) and Albert Tissandier

Vernenow fifty-six, a frequent yachter, and a very busy writerthought otherwise. Though in the thick of working on one of his longest novels,

Next page