HONOR DE BALZAC (17991850), one of the greatest and most influential of novelists, was born in Tours and educated at the Collge de Vendme and the Sorbonne. He began his career as a pseudonymous writer of sensational potboilers, before achieving success with a historical novel, The Chouans. Balzac then conceived his great work, La Comdie humaine, an ongoing series of novels in which he set out to offer a complete picture of contemporary society and manners. Always working under an extraordinary burden of debt, Balzac wrote some eighty-five novels in the course of his last twenty years, including such masterpieces as Pre Goriot, Eugnie Grandet, Lost Illusions, and Cousin Bette. In 1850, he married Mme. Eveline Hanska, a rich Polish lady with whom he had long conducted an intimate correspondence. Three months later he died.

RICHARD HOWARD is a poet and translator. He teaches in the School of Arts at Columbia University.

ARTHUR C. DANTO is the Johnsonian Professor of Philosophy Emeritus at Columbia University, art critic for The Nation, and author of many books about art and philosophy. He lives in Manhattan with his wife, Barbara Westman.

This is a New York Review Book

Published by The New York Review of Books

435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

www.nyrb.com

Translation copyright 2001 by Richard Howard

Introduction copyright 2001 by Arthur C. Danto

All rights reserved.

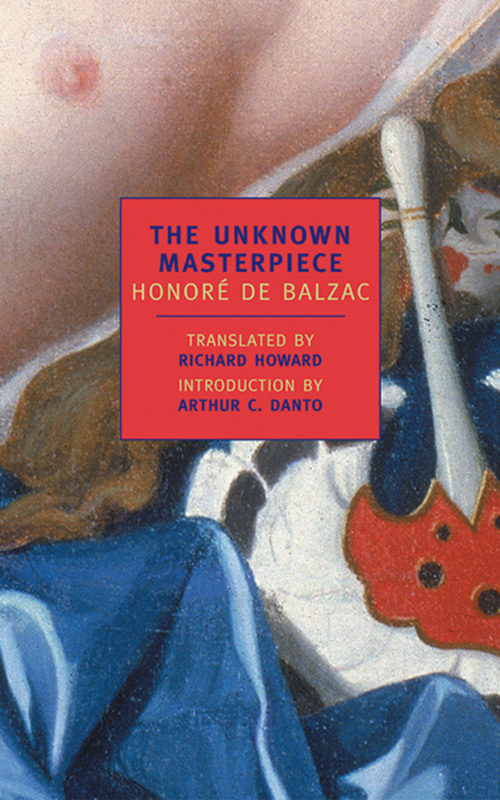

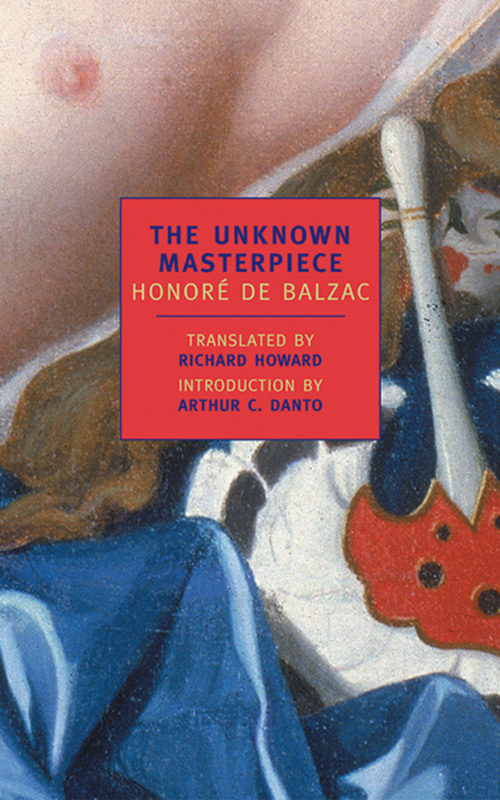

Cover image: Jean Auguste Dominique Ingres, Odalisque with Slave (detail), 1842

Cover design: Katy Homans

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Balzac, Honor de, 17991850.

[Chef duvre inconnu. English]

The unknown masterpiece ; and, Gambara / by Honor de Balzac ;

translated by Richard Howard ; introduction by Arthur C. Danto.

p. cm.

I. Title: Unknown masterpiece ; and, Gambara. II. Howard, Richard,

1929 III. Balzac, Honor de, 17991850. Gambara. English. IV. Title:

Gambara. V. Title.

PQ2163.C4 E5 2001

843'.7dc21

2001000399

eISBN 978-1-59017-415-9

v1.0

For a complete list of books in the NYRB Classics series, visit www.nyrb.com or write to:

Catalog Requests, NYRB, 435 Hudson Street, New York, NY 10014

GAMBARA

To the Marquis of Belloy

It was during afternoon tea at the fireside of a mysterious retreat which no longer exists save as memory will preserve it, overlooking Paris from the hills of Bellevue to those of Belleville, from Montmartre to the Arc de Triomphe, that amid the myriad ideas which exploded and expired like rockets in your sparkling conversation, you offered my pen, with characteristic generosity, this character worthy of Hoffmann, a bearer of unknown treasures and a pilgrim at the gates of Paradise, endowed with ears to hear angelic harmonies yet no longer a tongue to repeat them, touching the keyboard with fingers deformed by the contractions of divine inspiration, under the illusion he was playing celestial music to stupefied listeners. You created Gambara, I merely costumed him. Let me render unto Caesar the things which are Caesars, regretting you did not take up the pen at a period when noblemen might employ it as well as the sword in their countrys service. You may well take no thought for yourself, but your talents you owe to us.

New Years Day of the year one thousand eight hundred and thirty-one was emptying its packet of holiday sugarplums: four oclock had struck, restaurants were beginning to fill, and there was a crowd in the Palais Royal. Presently a carriage stopped at the entrance and out of it stepped a young man of proud bearing, doubtless a foreigner or he would not have been attended by such an aristocratically plumed footman nor displayed on his carriage doors the quarterings still coveted by heroes of the July monarchy. The stranger entered the Palais Royal and joined the crowd under the arcades, patient with the slow pace to which the press of idlers condemned his progress. He appeared accustomed to the measured gait ironically known as an ambassadors walk, though his dignity seemed a trifle theatrical: handsome and severe as his countenance was, his hat, beneath which emerged a tuft of curly black hair, tilted perhaps a little too far over his right ear, belying his gravity by a slightly roguish look; his inattentive, half-closed eyes cast disdainful glances at the crowd.

Now theres a really good-looking man, murmured a shopgirl, stepping aside to let him pass.

Whos well aware of the fact, her homely companion replied in a loud voice.

After a turn around the arcades, the young man glanced at the sky and then at his watch, made an impatient gesture, and entered a tobacconists shop where he lit a cigar and lingered in front of a mirror to inspect his clothes which were a little showier than the laws of French taste prescribe. He fiddled with his collar, tugged at a black velvet vest crisscrossed by one of those heavy gold chains made in Genoa, and, casually flinging over his left shoulder a velvet-lined cloak which he then rearranged with some care, the young man resumed his promenade without permitting himself to be distracted by the appraising glances that marked his progress. When lights began to appear in the shops and the evening seemed dark enough, he headed toward the Place du Palais Royal like a man afraid to be recognized, skirting the square till he reached the fountain where, shielded by the line of fiacres, he entered the dark, dirty, and disreputable rue Froidmanteau, a sort of sewer the police tolerate near the well-swept Palais Royal, the way an Italian majordomo allows a careless footman to leave a pile of household trash in a corner of the staircase. The young man hesitated, for all the world like a suburban matron in her Sunday best anxiously peering across a rain-swollen gutter. Yet the hour was well chosen to satisfy even the most shameful fantasy: earlier one might be found out, later one might be forestalled. To have let himself be lured by one of those glances that prompt without being exactly provocative; to have followed for an hour, perhaps even a whole day, some lovely young woman idealized in his thoughts, her most trivial actions interpreted a thousand flattering ways; to have started believing in sudden, irresistible sympathies; to have imagined, in the heat of a passing exhilaration, an adventure in an age when romances are written precisely because they no longer occur; to have dreamed, wrapped in Almavivas cloak, of balconies and guitars, of stratagems and locks; to have written a rapturous poem and now be standing at an ill-famed door; and thenfor a grand finale!to discover his Rosinas decorum to be no more than a precaution imposed by a police regulationis not all this a disappointment many men have endured without admitting it? The most natural emotions are those we acknowledge with the most repugnance, and conceit is surely one of these. When the lesson stops there, a Parisian will profit by it or put it out of his mind, and no great harm is done; but this is scarcely the case for a foreigner about to discover how much his Parisian education may cost.

This stroller was a Milanese nobleman banished from his country, where several liberal escapades had rendered him persona non grata to the Austrian government. Count Andrea Marcosini had found himself welcomed to Paris with that entirely French enthusiasm invariably encountered by a lively wit and a resonant name accompanied by two hundred thousand francs a year and a charming presence. For such an individual, exile was a pleasure trip; his property was merely sequestrated, and his friends informed him that after an absence of two years at the most, he could reappear in his homeland without the slightest danger. After rhyming