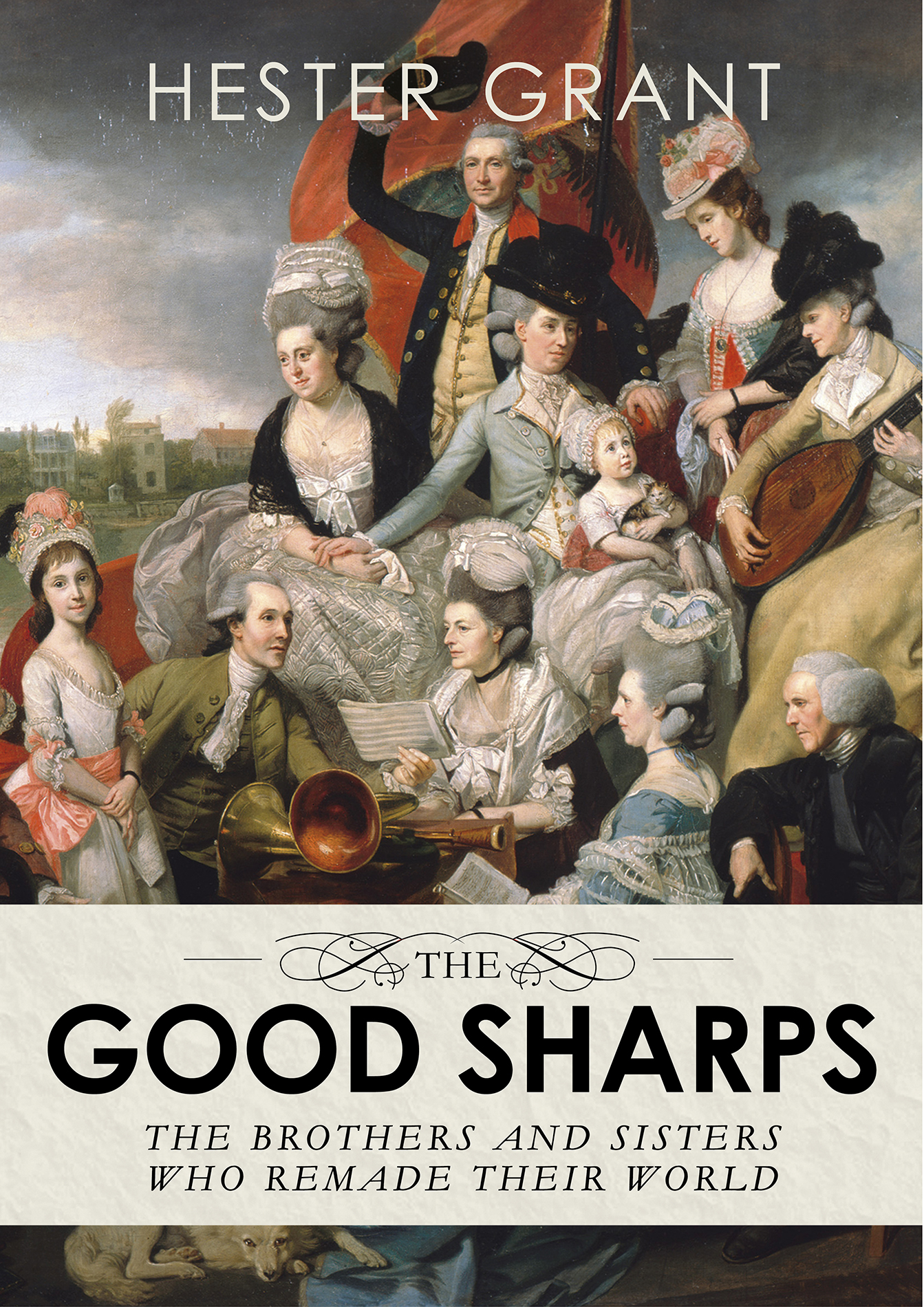

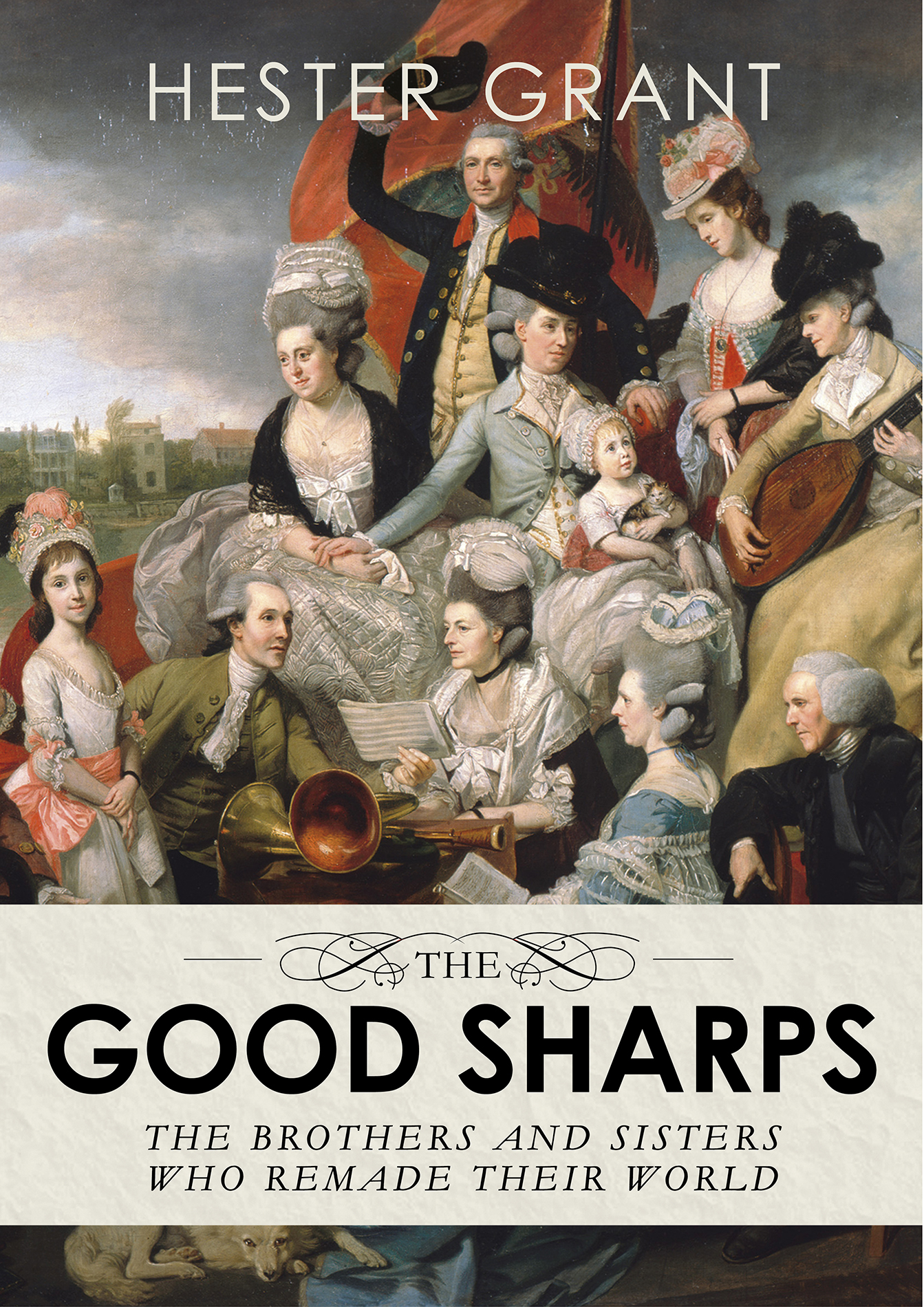

Hester Grant

THE GOOD SHARPS

The Brothers and Sisters Who Remade Their World

Contents

About the Author

Hester Grant studied modern history at Christ Church, Oxford, where she was awarded the J. L. Field Exhibition and the Keith Feiling History Prize. She subsequently trained and practised as a barrister. Hester gave up her legal career to bring up her three children, and to pursue her great loves of writing and eighteenth-century British history. Her fascination with the Sharps began when she saw their portrait at the 2012 Johan Zoffany exhibition at the Royal Academy.

In memory of my father

Picture Credits

The South West View of the City of Durham (1776) archivist 2015/Alamy Stock Photo;

Charles White, View of the River Thames from Chelsea (1750) Guildhall Library & Art Gallery/Heritage Images/Getty Images;

Michael Angelo Rooker, A View of the Princes House at Kew (1776) The Print Collector/Getty Images;

Robert Laurie, View of Fulham from the White Lion Inn, Putney (1783) Guildhall Library & Art Gallery/Heritage Images/Getty Images.

Johan Joseph Zoffany, The Sharp Family (177981), from a private collection; on loan to the National Portrait Gallery, London.

Johan Joseph Zoffany, Self-Portrait with His Daughter Maria Theresa, James Cervetto, and Giacobbe Cervetto (1780): Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection;

Engraving of Thomas Sharp, from The works of Thomas Sharp, D.D. Late Archdeacon of Northumberland, and Prebendary of Durham, in six volumes (1763), shelf mark Bamburgh K.7.17. Reproduced by permission of Lord Crewes Charity and of Durham University Library;

Thomas Bowles, The South West Prospect of London, from Somerset Gardens to the Tower (1750): Yale Center for British Art, Paul Mellon Collection;

Letter from Granville Sharp to his sisters dated 18 October 1757 (D3549 7/2/15), from the Lloyd Baker archive. Reproduced by kind permission of Gloucestershire Archives.

James Sharp, manufacturer of agricultural impliments, eighteenth-century advert Culture Club / Getty Images;

Two views of a bladder stone (D3549 10/1/3), from the Lloyd Baker archive. Reproduced by kind permission of Gloucestershire Archives.

Charles Turner, after J. Abbot, William Sharp (1784) National Portrait Gallery, London;

Portrait of English abolitionist, scholar and philanthropist Granville Sharp (17351813), from Encyclopaedia Londinensis (1827) The Print Collector/Alamy Stock Photo;

Steel-engraved antique print of Wicken Park, Northamptonshire (1847), from a drawing by J. P. Neale.

Johan Joseph Zoffany, Queen Charlotte (17441818) with members of her family (c. 17712) Royal Collection Trust/Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020;

Johan Joseph Zoffany, George III (17381820) (1771) Royal Collection Trust/Her Majesty Queen Elizabeth II 2020.

Bamburgh Castle, in Northumberland, from The Antiquities of England and Wales by Francis Grose Antiqua Print Gallery/Alamy Stock Photo;

James Hayllar, Granville Sharp (17351813), The Abolitionist, Rescuing a Slave from The Hands of His Master (1864) Victoria and Albert Museum, London.

Johan Joseph Zoffany, A View in Hampton Garden with Mr and Mrs Garrick Taking Tea (1762). Courtesy of the Garrick Club, London;

The Sharp family flotilla, from a painting in the private collection of the Lloyd-Baker family, reproduced by kind permission of the Lloyd-Baker Estate.

The good Sharps! None ever spoke of them without good before their name!

annie raine ellis , Sylvestra: Studies of Manners in England from 1770 to 1800, Vol. 1 (1881)

Overture

When Johan Zoffany returned to London, in the spring of 1779, it was on the crest of a gilded wave. Flushed with the triumph of his reception in the Habsburg courts of Europe, the German artist could boast to his friends in the expatriate community of musicians, singers, sculptors and engravers that thrived in cosmopolitan London at that time, of the patronage of Pietro Leopoldo, Grand Duke of Tuscany, of the Duke and Duchess of Bourbon-Parma and of the empress Maria Theresa herself. Had she not ordered him to travel from Florence to her palace in Vienna with his unfinished painting of Duke Leopoldos family, in a specially adapted carriage? And afterwards, in recognition of his services to the imperial majesty, bestowed on him the title of Baron of the Holy Roman Empire? With such testimonials, and the proceeds of his continental commissions swelled by a speculative trade in the sale of old masters, Zoffany could look forward to the revival of his English portrait practice, and a life of extravagant ease.

Perhaps, in the weeks that followed, as he fingered the exquisite furnishings of his newly acquired town house in Albemarle Street, or sauntered along the Thames by his country home at Strand-on-the-Green, Zoffany pondered on the glories of this homecoming, and compared it to his arrival in London nineteen years before. Then he had been a nobody, an obscure artist from Regensburg, whose sole claim to fame was a series of murals in the chapel and palace of the Archbishop of Trier at Koblenz.

Behind the constant revolutions of Zoffanys life lay a restless ambition that the rewards of an ordinarily comfortable existence did not satisfy. Impulsive, capricious and intellectually curious, the artist sought stimulation in new experience, while his delight in the material trappings of wealth demanded a steady stream of rich clients. It was a quest for adventure, and a newly acquired interest in the art and antiquities of the East, as well as the lure of the riches of the East India Company Zoffany anticipates to roll in gold dust noted his fellow artist Paul Sandby that inspired his travels in India in the 1780s.

It was on his return from Italy and Vienna in the spring of 1779, when his travels in India still lay ahead of him, that Zoffany was approached by William Sharp, a London surgeon, with a request to paint a portrait of his extended family. Fresh from the resplendence of the Habsburg court, the German artist might have looked askance at the advances of a client of a distinctly sub-aristocratic hue. But Zoffanys portrait practice had failed to live up to the glorious promise of his homecoming. Instead of a revival of royal and noble favour, he had been shunned at court partly on account of his failure to obtain the kings permission before accepting a title from the empress Maria Theresa while fashion now favoured the grand style of portraiture practised by Joshua Reynolds and George Romney in preference to his own more muted sensibility. In these circumstances, Zoffany could hardly afford to be contemptuous of the 400-guinea fee a vast sum for the time agreed for the painting of the Sharp family.

There were other reasons why Zoffany looked kindly on the Sharp commission. Patron and artist shared a passionate love of music, which each indulged by throwing musical water parties on barges on the Thames, and had friends in common such as the German musicians Johann Christian Bach and Carl Friedrich Abel. There was also a synchronicity between William Sharps journey from middle-class obscurity to wealth and position, and Zoffanys own. Both enjoyed a remarkable talent for society, that in Zoffanys case facilitated his acceptance by groups as diverse as the patricians whose portraits he painted in the late 1760s, louche expats in Florence, and the intellectuals who met at Jacks Coffee House every Wednesday evening to discuss natural history, amongst them the naturalist Daniel Solander, Captain James Cook and Josiah Wedgwood. Occasionally Zoffany overstepped the mark, as when he offended Lord Cowper by wearing a pink coat in Rome apparently the preserve of English earls but mostly his social instincts were pitch perfect.

Next page