BORDER RADIO

Quacks, Yodelers, Pitchmen, Psychics, and Other Amazing Broadcasters of the American Airwaves

REVISED EDITION

GENE FOWLER & BILL CRAWFORD

FOREWORD BY WOLFMAN JACK

University of Texas Press

Austin

Copyright (c) 2002 by Gene Fowler and Bill Crawford All rights reserved

First University of Texas Press edition, 2002

Fourth paperback printing, 2006

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to Permissions, University of Texas Press, P.O. Box 7819, Austin, TX 78713-7819.

http://utpress.utexas.edu/index.php/rp-form

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS CATALOGING-IN-PUBLICATION DATA Fowler, Gene, 1950

Border radio : quacks, yodelers, pitchmen, psychics, and other amazing broadcasts of the American airwaves / by Gene Fowler and Bill Crawford.-Rev. ed.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 13 978-0-292-72535-5

1. Radio broadcastingMexican-American Border Region. I. Crawford, Bill, 1955-II. Title.

PN1991.3.U6 F66 2002

384.54'0972'1dc21

2001037616

ISBN 978-0-292-75971-8 (library e-book)

ISBN 978-0-292-78914-2 (individual e-book)

DOI: 10.7560/725386

Foreword

BY WOLFMAN JACK

First off, if it wasnt for border radio, I doubt very much if there ever wouldve been a Wolfman Jackat least not the Wolfman Jack you and I have come to know.

It was those 250,000 watts, baby, each and every one of em making their way across the continent, getting into every city, every little town and hamlet, cuttin through the night like a knife through a thick fog.

We will probably never again see the likes of it. Times have changed, and its hard to imagine anyone like Dr. Brinkley doing his thing over the airwaves again. Or the voices of Reverend Ike and well, even the Wolfman has never really been the same as back in the days of XERF and XERB.

Border Radio succeeds in its attempt to explain to you not only how this phenomenon of broadcasting affected the industry but also how it influenced a whole generation of peoplepeople like George Lucas. Border radio inspired his motion picture American Graffiti, which took me outta the shadows and gave a whole new dimension to my career.

In this book youll get quite a vivid picture of outlaw broadcasting, so to speak. And youll realize how something like this could only have happened when it did, with the characters it did.

But most of all, Border Radio reminds us all of the magic that enlivened the airwaves when hundreds of thousands of watts were let loose, and all of us involved were allowed to shuck and jive and explore new areas of broadcasting. And youll learn how the magic was destroyed by everyday forces like politics and greed.

Ya know, its a fact that everything ever broadcasted stays out there in the stratosphere, and sometimes, through some fluke of transmission, old sounds return exactly as they were originally heard. So if one night youre cuddled up in bed with the radio on and the moon gleaming through your window, and suddenly you hear a strange static followed by a howl, or a plea to get a goat-gland operation, or a voice tellin you to send a few hard-earned bucks for a reverends down-home church, listen closely you are most likely in tune with the magic that was border radio.

Introduction: Turn Your Radio On

and youll be free.

TURN YOUR RADIO ON, HYMN SUNG BY RHUBARB RED AND HIS RUBES, ADAPTED FROM A SONG WRITTEN BY ALBERT E. BRUMLEY AND BROADCAST OVER XEG, MONTERREY, MEXICO, 1940S

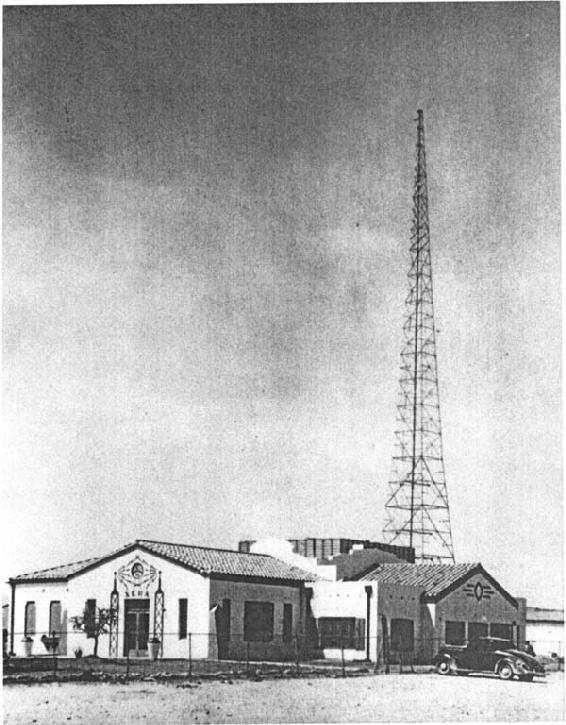

In the Old West, it was not unusual for outlaws to make a break for the Mexican border. More than a few rebellious souls took refuge in her sleepy villages and desert oases. Decades after the last desperado splashed across the Rio Grande, a new breed of badmen crossed to the rivers southern banks. The radio outlaws who built and operated the superpowered broadcasting stations just south of the border between 1930 and the mid-1980s stood in this tradition. The men and women who created border radio were frontiersmen of the ether, imaginative experimenters who came to la frontera seeking freedom from the restrictions of the American media establishment. By building huge transmitters and testing new and untried formats, these pioneers created a proving ground for many of the technical, legal, and programming aspects of todays broadcasting industry, and they managed to be quite entertaining as well.

At the turn of the twentieth century, Americas airwaves were a virgin communication wilderness, barely touched by Guglielmo Marconis recent discovery, the wireless. The transmission of voices through the North American airwaves began on Christmas Eve, 1906, when Reginald Aubrey Fessenden fired up his experimental radio station at Brant Rock, Massachusetts. Wireless operators on ships off the East Coast, listening on their headsets for the short electronic burst of messages in Morse code, were astounded to hear a woman singing. They called in ships officers and other technicians to experience this wireless miracle and thrilled to the sound of a violin soloist performing O, Holy Night. With this successful experimental broadcast of his own violin performance, Fessenden displayed one of the most important capabilities of Marconis invention: the capability of sending the human voice out through the heavenly ether.

Following the lead of this media trailblazer, hundreds of amateur radiophiles leapt into the world of the wireless, which soon became known as radioshort for radiotelegraphy. They filled their attics with wires, Leyden jars, and the other paraphernalia necessary to transmit and receive the magical radio signals. They watched sparks flash brilliantly across homemade receivers and tweaked tuning crystals with thin wires called cats whiskers as they strained to hear the secrets of the airwaves. When one devoted band of radio enthusiasts heard a musical broadcast for the first time, they called in the neighbors just to make sure that not a single one of us was having a daydream. Some spent their evenings searching the electromagnetic spectrum, trying to make contact with ships at sea, while others tuned in faraway time signals and marveled at the ability of man to conquer distance. In 1912 the U.S. government passed the first laws concerning radio broadcasting. Within five years, more than 8,500 transmitting licenses had been issued, and a chorus of radio voices was creating an amateur clamor in the American heavens.

World War I brought an end to the squawking, as the Navy ordered all transmitters off the air to keep the airwaves clear for the vital function of ship-to-shore communication. At the close of the war, the Navy tried to maintain control of all broadcasting, arguing that the medium was too important to be managed by private commercial interests. But when the doughboys returned from France, radio amateurs returned to the ether, and federal officials decided to let free enterprise determine the fate of American broadcasting.

Americas fascination with radio soon turned into an obsession. In the first issue of Radio Broadcast magazine, published in 1920, the editors commented on the growth of the new medium, writing that the rate of increase in the number of people who spend at least part of their evening listening in is almost incomprehensible. Colleges, churches, newspapers, department stores, radio manufacturers, hundreds of enterprising individuals, and even stockyards started their own stations. Jazz bands, poets, starlets, and elephants broadcast live in a rush of largely unrehearsed programming. The number of stations mushroomed from just 8 in 1921 to 564 in 1922, and investment in radio equipment zoomed from $60 million in 1922 to $358 million in 1924.