THREE GOTHIC NOVELS

HORACE WALPOLE (171797), fourth earl of Orford, was the son of Robert Walpole, twice Prime Minister of Britain. In 1747 he moved to Strawberry Hill, Twickenham, his little Gothic castle, where he was at the centre of a literary and political society and arbiter of taste. The Castle of Otranto was published anonymously in 1764 and launched the Gothic novel in England. Walpole is also remembered for his witty letters to a wide circle of friends.

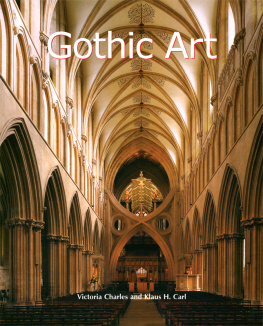

WILLIAM BECKFORD (17591844) was the son of a Lord Mayor of London and at one time was known as Englands wealthiest son, with a fortune derived from the West Indies. He built Fonthill Abbey in Wiltshire, a prime example of Gothic architecture, where he lived until scandal and extravagance forced him to sell. Vathek, originally written in French, was published in 1786.

MARY SHELLEY (17971851) was the daughter of the philosopher and writer William Godwin and of Mary Wollstonecraft, author of Vindication of the Rights of Woman. In 1814 she eloped with the poet Shelley to the continent, marrying him on the death of his first wife. Frankenstein (1818) was written during a stay in Switzerland when she, Shelley and Byron each agreed to write a supernatural story.

MARIO PRAZ Professor of English Language and Literature at the University of Rome until 1966. He wrote a great many books on literature, many of them in English. He died in 1982.

PETER FAIRCLOUGH graduated with an English degree from Durham University and teaches English in Lancashire. He has also edited Oliver Twist, Dombey and Son and The Last Chronicle of Barset for the Penguin Classics.

THREE GOTHIC NOVELS

Edited by Peter Fairclough

with an Introductory Essay by

Mario Praz

THE CASTLE OF OTRANTO

Horace Walpole

VATHEK

William Beckford

FRANKENSTEIN

Mary Shelley

PENGUIN BOOKS

PENGUIN BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England

Penguin Putnam Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Books Australia Ltd, 250 Camberwell Road, Camberwell, Victoria 3124, Australia

Penguin Books Canada Ltd, 10 Alcorn Avenue, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4V 3B2

Penguin Books India (P) Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Books (NZ) Ltd, Cnr Rosedale and Airborne Roads, Albany, Auckland, New Zealand

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, 24 Sturdee Avenue, Rosebank 2196, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R ORL, England

www.penguin.com

Published in the Penguin English Library 1968

Reprinted in Penguin Classics 1986

32

Notes copyright Peter Fairclough, 1968

Introductory Essay copyright Mario Praz, 1968

All rights reserved

Except in the United States of America, this book is sold subject

to the condition that it shall not, by way of trade or otherwise, be lent,

re-sold, hired out, or otherwise circulated without the publishers

prior consent in any form of binding or cover other than that in

which it is published and without a similar condition including this

condition being imposed on the subsequent purchaser

EISBN: 9780141905624

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTORY ESSAY

THE favour recently enjoyed in some European countries (Italy for instance) by Gustav Meyrinks The Golem and Mikhail Bulgakovs The Master and Margarita makes one wonder whether the scanty fare provided by modern experimental novels and anti-romans has made readers so famished, that as soon as they happen to detect the smell of what the French romantics used to call the roman-charogne, they rush for it like mad. The terror and wonder which abound in those two novels have certainly profited also by the example of modern masters, but a reader familiar with the Gothic novels of the end of the eighteenth and the beginning of the nineteenth century will easily recognize in them themes and proceedings which were the stock-in-trade of the tales of terror. The terrific robot of the modern Prague banker is of the same lineage as Mary Shelleys monster, and the underground labyrinth through which the protagonist reaches the awesome room of the dark Jewish school is a commonplace of the Gothic tales, the double is a descendant of many a German Doppelgnger, the motif of the innocent accused and tried for a crime he has not committed, and incapable of proving his innocence, recalls episodes in Frankenstein, in Melmoth the Wanderer and in Franois Soulis Mmoires du diable. In fact, though refined by the lesson of the later masters of the mysterious and the cruel, such as Kafka in fiction and Kubin in painting, the subject-matter of The Golem has such a distinct Gothic flavour that tracing its literary genealogy would take us very far, because on the one hand there is the Rosicrucian strain which begins with Godwins later novels and gains in strength through Hawthornes posthumous work, on the other hand there are Novaliss And in the posthumous work of the Russian novelist there is a devilish cat who descends from Hoffmanns Kater Murr, a man who lacks a shadow like Chamissos Peter Schlemihl, besides obvious echoes of Goethes Faust, of Gogol, and the Wandering Jew.

All this shows that the Gothic flame, as an Indian scholar has called it, is far from extinguished. The appeal of terror and mystery no doubt existed also much earlier than the second half of the eighteenth century, witness the Hellenistic romances and the Elizabethan dramas, but it is in the last portion of that century that in fiction we meet with no less strange fashions than those of the merveilleuses and the incroyables of the Directory, which historians of costume quote as typical instances of the extravagant finery that usually either accompanies or follows epochs of great social revolutions. Thus about the time of the French Revolution there appeared in France the series of infernal novels of the Marquis de Sade, and in England a whole blossoming of Gothic novels, called tales of terror there and romans noirs abroad. The effect, in a survey of literary history, is not unlike the impression we receive in an air journey over Texas and New Mexico to the Grand Canyon, when we see a level plain suddenly interrupted by chains of craggy mountains, with rocks which have the aspect of ruined castles and ranges of convulsed peaks like a tumultuous barbaric horde.

And in the same way as such a full orchestra of the horrid Perhaps the origin of the painful pleasure imparted by the tales of terror is contained in two lines of Baudelaire (Au lecteur Les Fleurs du Mal):

C est lEnnui! Loeil charg dun pleur involantaire

Il rve dchafauds en fumant son houka.

The new sensibility had begun to find literary expression in compositions such as Collinss Ode to Fear and in The Castle of Otranto, written by Walpole as the whim of a dilettante mediaevalist; it had modified the conception of it had sought to analyse its own origins in such essays as that of J. and A. L. Aikin On the Pleasure derived from Objects of Terror, and the Enquiry into those kinds of Distress which excite agreeable sensations (in