THIS IS A BORZOI BOOK

PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF AND ALFRED A. KNOPF CANADA

Copyright 2016 by A. Hope Jahren

All rights reserved. Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Penguin Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Alfred A. Knopf Canada, a division of Penguin Random House Canada Ltd., Toronto.

www.aaknopf.com

www.penguinrandomhouse.ca

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Penguin Random House LLC.

Knopf Canada and colophon are trademarks of Penguin Random House Canada Ltd.

Portions of Chapter 1 originally appeared in Nautilus, Issue 34: Adaptation (nautil.us), as My Family, My Science on March 3, 2016.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Jahren, Hope.

Title: Lab girl / Hope Jahren.

Description: First edition. | New York : Alfred A Knopf, 2016. | A Borzoi Book. | Includes bibliographical references.

Identifiers: LCCN 2015024305 | ISBN 9781101874936 (hardcover : alk. paper) | ISBN 9781101874943 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Jahren, Hope. | BiologistsUnited StatesBiography. | GeobiologyResearchAnecdotes.

Classification: LCC QH31. J344 A3 2016 | DDC 570.92dc23 LC record available at http://lccn.loc.gov/2015024305

Library and Archives Canada Cataloguing in Publication

Jahren, Hope, author

Lab girl / Hope Jahren.

Includes bibliographical references.

Issued in print and electronic formats.

ISBN 978-0-345-80986-5

eBook ISBN 978-0-345-80988-9

1. Jahren, Hope. 2. Women botanistsUnited StatesBiography. 3. Women scientistsUnited StatesBiography. 4. Manic-depressive personsUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

QK31.J33A3 2016 580.92 C2015-907335-9

eBook ISBN9781101874943

Lab Girl is a work of nonfiction. To protect the privacy of others, certain names have been changed, characters conflated, and some incidents condensed.

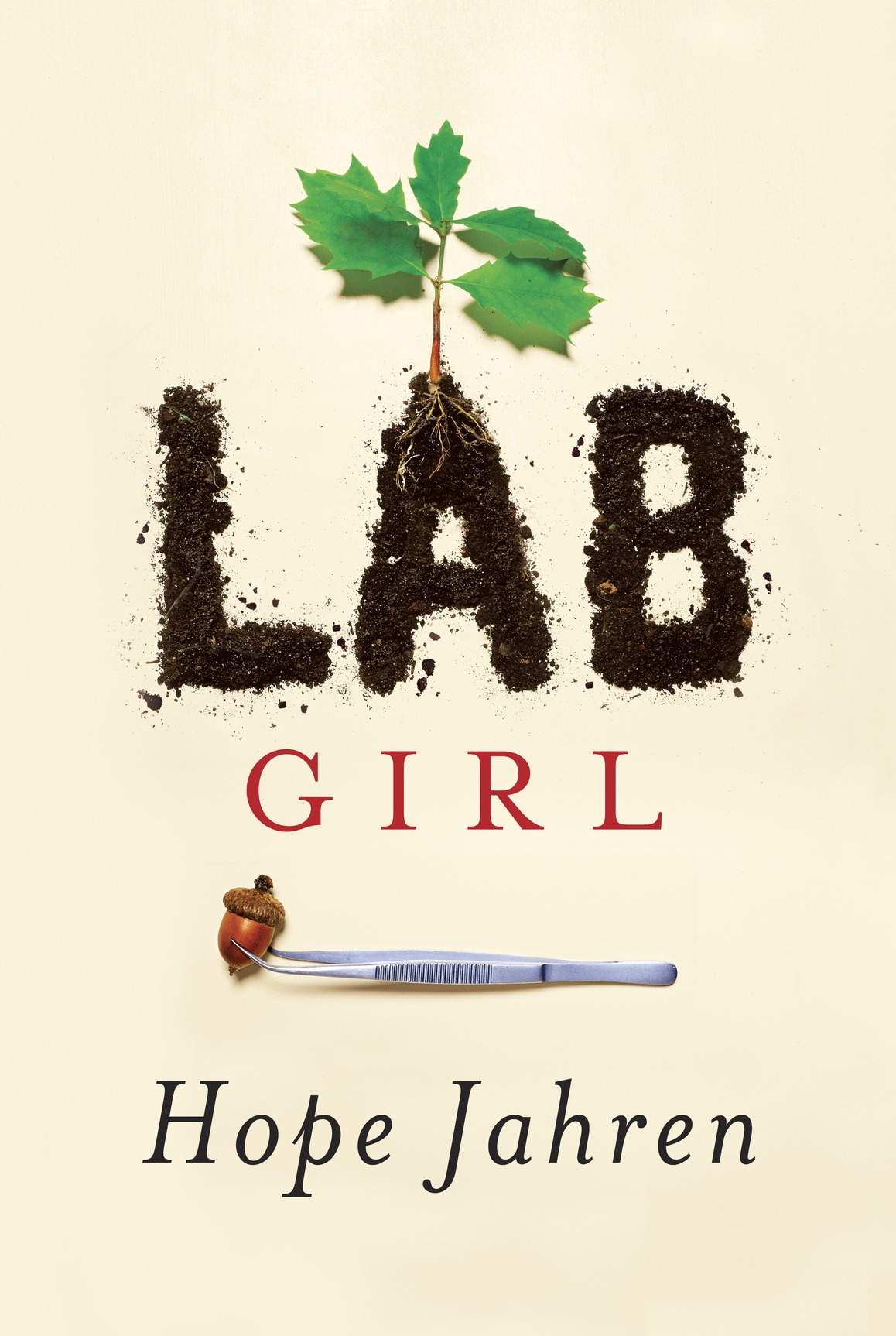

Cover photographs by Jon Shireman

Cover design by Kelly Blair

v4.1_r4

ep

Contents

Everything that I write is dedicated to my mother.

The more I handled things and learned their names and uses, the more joyous and confident grew my sense of kinship with the rest of the world.

Helen Keller

Prologue

PEOPLE LOVE THE OCEAN. People are always asking me why I dont study the ocean, because, after all, I live in Hawaii. I tell them that its because the ocean is a lonely, empty place. There is six hundred times more life on land than there is in the ocean, and this fact mostly comes down to plants. The average ocean plant is one cell that lives for about twenty days. The average land plant is a two-ton tree that lives for more than one hundred years. The mass ratio of plants to animals in the ocean is close to four, while the ratio on land is closer to a thousand. Plant numbers are staggering: there are eighty billion trees just within the protected forests of the western United States. The ratio of trees to people in America is well over two hundred. As a rule, people live among plants but they dont really see them. Since Ive discovered these numbers, I can see little else.

So humor me for a minute, and look out your window.

What did you see? You probably saw things that people make. These include other people, cars, buildings, and sidewalks. After just a few years of design, engineering, mining, forging, digging, welding, bricklaying, window-framing, spackling, plumbing, wiring, and painting, people can make a hundred-story skyscraper capable of casting a thousand-foot shadow. Its really impressive.

Now look again.

Did you see something green? If you did, you saw one of the few things left in the world that people cannot make. What you saw was invented more than four hundred million years ago near the equator. Perhaps you were lucky enough to see a tree. That tree was designed about three hundred million years ago. The mining of the atmosphere, the cell-laying, the wax-spackling, plumbing, and pigmentation took a few months at most, giving rise to nothing more or less perfect than a leaf. There are about as many leaves on one tree as there are hairs on your head. Its really impressive.

Now focus your gaze on just one leaf.

People dont know how to make a leaf, but they know how to destroy one. In the last ten years, weve cut down more than fifty billion trees. One-third of the Earths land used to be covered in forest. Every ten years, we cut down about 1 percent of this total forest, never to be regrown. That represents a land area about the size of France. One France after another, for decades, has been wiped from the globe. Thats more than one trillion leaves that are ripped from their source of nourishment every single day. And it seems like nobody cares. But we should care. We should care for the same basic reason that we are always bound to care: because someone died who didnt have to.

Someone died?

Maybe I can convince you. I look at an awful lot of leaves. I look at them and I ask questions. I start by looking at the color: Exactly what shade of green? Top different from the bottom? Center different from the edges? And what about the edges? Smooth? Toothed? How hydrated is the leaf? Limp? Wrinkled? Flush? What is the angle between the leaf and the stem? How big is the leaf? Bigger than my hand? Smaller than my fingernail? Edible? Toxic? How much sun does it get? How often does the rain hit it? Sick? Healthy? Important? Irrelevant? Alive? Why?

Now you ask a question about your leaf.

Guess what? You are now a scientist. People will tell you that you have to know math to be a scientist, or physics or chemistry. Theyre wrong. Thats like saying you have to know how to knit to be a housewife, or that you have to know Latin to study the Bible. Sure, it helps, but there will be time for that. What comes first is a question, and youre already there. Its not nearly as involved as people make it out to be.

So let me tell you some stories, one scientist to another.

1

THERE IS NOTHING in the world more perfect than a slide rule. Its burnished aluminum feels cool against your lips, and if you hold it level to the light you can see Gods most perfect right angle in each of its corners. When you tip it sideways, it gracefully transfigures into an extravagant rapier that is also retractable with great stealth. Even a very little girl can wield a slide rule, the cursor serving as a haft. My memory cannot separate this play from the earliest stories told to me, and so in my mind I will always picture an agonized Abraham just about to almost sacrifice helpless little Isaac with his raised and terrible slide rule.

I grew up in my fathers laboratory and played beneath the chemical benches until I was tall enough to play on them. My father taught forty-two consecutive years worth of introductory physics and earth science in that laboratory, nestled within a community college deep in rural Minnesota; he loved his lab, and it was a place that my brothers and I loved also.