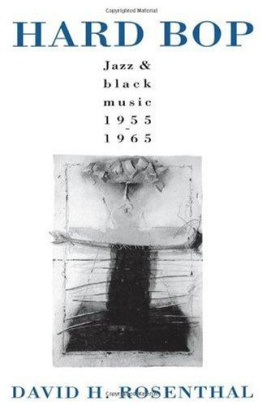

JAZZ AND

BLACK MUSIC

19 5 5-1965

DAVID H. ROSENTHAL

PREFACE

My brother David wasfourteen (I was ten) when he discovered jazz while attending one of those musicand art summer camps in the Berkshires. Chuck Israels, soon to be Bill Evans'sbassist, was the son of the woman who ran the place. Randy Weston, a fabulouspianist, would drop by to play basketball. Within a year, David knew more aboutjazz than many adult jazz-lovers ever do (many of the thoughts contained inthese pages were already being expressed), and had managed by hook or crook togather around himself a very serious little record collection.

At this time (1960),almost all the musicians David discusses in this book were hard at workcreating sounds that are still lighting fires under jazz enthusiasts."Hard bop," whatever the hotly-debated merits of the term, was"alive," by which I mean not just that the music was being played (asit still is), but that it was responding with passionate urgency (as itemphatically no longer is) to its own imbedded implications and those of thelarger surrounding culture. It was in, of, and about the world in which itlived.

To David, a poet, critic,and savvy observer of the chaotic postwar world, this quality of currency wasnever secondary throughout his thirty-year involvement in jazz. Music was only one of the trouble spotshe kept an eye on, and he was untiringruthless, reallyin his determination topull it all together. Not a jazz musician but a jazz-loving artist who was verymuch of like mind, David was the perfect man for the job of chronicling thecomplex processes by which jazz flowed into and out of its "hip"environs. He especially relished those dizzying moments when some new artisticflowering, individual or collective, would swoop down to startle sleepyexpectations.

Conversely, he distrustedart that had been cut off from its own time to drift, encapsulated and revered,into the future. As the last chapters of this book were being completed, itappeared that jazz might be headed for just such a fate. The "nostalgicnineties" were in full swing (more people probably heard John Lennon's"Imagine" in 1991 than during the entire 1970s). The big jazz labels,seeking salvation by promoting a small group ofeighteen-to-twenty-five-year-old males as the "young lions" of theirgeneration, had giddily exhumed a number of early-sixties musical, demographic,and sartorial cliches. Lincoln Center launched a successful jazz program, whilepreviously all-classical magazines and record outlets expanded theirwell-guarded boundaries just far enough to include jazz. Such intimations ofrespectability made it seem that "standard repertoire" classicalmusic and 1945-1970 jazz were preparing to share a single high-toned niche inthe twenty-first century.

David was disheartened bysuch possibilities. We spent many hours brooding together over thepost-apocalyptic state of our beloved culture, a state he once likened to agarbage can that had been overturned on a windy day. As jazz musicians andlisteners continually readjust their fix on the music's future, strength andsanity can be derived from David's refusal to "dumb down" the past interms of later developments. It was utterly characteristic of him to write (inChapter 3), "Jazz has always been a volatile music, changing quickly andoften, and the hard-bop period ... represents a moment of balance and polish in the workof many musicians.... (But) the elegant equilibriums thus achieved cannot besustained for long. Such styles generate their own pressures for radicalchange." No one would cite the jazz of the last fifteen years as a shiningexample of healthy evolution; David's use of the present tense in this passagetypifies his uncompromising attitude.

David completed thewriting of this book in 1990. Although he continued following the jazz sceneafter that, his views on the music discussed here, molded by a lifetime ofintense concentration, remained about the same. The major exception to this wasthe pianist Elmo Hope. In 1991, Blue Note reissued Hope's two ten-inch LPs,from 1953 and 1954, on CD. David was struck by the strength, focus, andoriginality of the 1953 trio date (with Percy Heath on bass and Philly JoeJones on drums). He felt that he had been too dismissive of Hope's pre-1959playing, and realized that inadequate rehearsal opportunities and the exigenciesof heroin had conspired to misrepresent Hope as much more of a "latebloomer" than he really was. Many of the qualities David described inHope's Hifijazz and Riverside albums can be heard to only slightly lessstunning effect on this wonderful earlier session.

Finally, a personal note.Although David and I certainly had our differences in musical outlook, there isno point in pretending otherwise: his view of the jazz universe, the thoughtscontained in these pages, were the mother's milk that started and guided me inmy life as a jazz pianist. As my family continues struggling with the emptinessleft by his unexpected illness and death, this "piece" of him,recalling so powerfully the smoke-filled, jazz-filled hours we spent together,is a tremendous comfort.

Alan Rosenthal April 28,1993

C ONTENTS

I NTRODUCTION

In January 1972, in ascene straight out of "Frankie and Johnny," trumpeter Lee Morgan wasshot dead by his mistress at Slug's, a jazz club on New York City's Lower EastSide. Morgan was thirty-three years old. His deathspectacular in jazz not somuch because he was young as because it involved a woman instead of drugsisremembered thus by one of his closest musical associates: "For years Leehad been with Helen [More], an older womanmaybe ten years older than him whosort of looked after him and had straightened him out a little, helped him stayaway from dope. A few weeks before his death, Lee had started hanging out witha younger girl, very pretty; she looked like Angela Davis. He was taking herall over town, showing her off to his friends. One day he dropped by the schoolin Harlem where I was teaching jazz workshops and introduced her to all of us.

"That night inJanuary was one of the coldest nights of the year. It was about five degreesbelow zero, and Lee was relaxing between sets at the bar with this fine newgirlfriend of his when Helen walked in. She came up to him, but Lee didn't wantto be bothered and he walked her over to a table, sat her down, and told her towait. Then he went back to the bar. After a while she came up to him again.This time Lee took her by the shoulders and, without her overcoat or anything,marched her over to the door and put her out in the cold. Now she had Lee'spistol in her pocketbook, and when she came back in she pulled it out and shothim: one of those shots that go straight to the heart. A little red stain cameup on his shirtthe bleeding was all insideand a few minutes later he wasdead. Then she realized what had happened and she was crying and hanging overhim and screaming 'Mogie'that was what she called him'What have I done?' Buthe was dead."*

In a number of respects,Morgan could be considered a quintessentialor even the quintessentialhardbopper. His sardonic, "dirty" solos, full of aggressively bent,half-valved, and smeared notes, epitomized the "badness" many jazzmenof his school strove to achieve. Like James Brown in soul music, he had honedhis time, attack, and timbre to razor sharpness. The development of his style,from its early bebop-influenced phase when he was with Dizzy Gillespie's bigband to the surging modal compositions of his later records, closely paralleledhard bop's evolution. Morgan's life and personalitythe moody arrogance thatstill glares out at us from so many photos, and his readiness to live willfullyfor the momentwere also those of a typical jazz hipster of the era. Finally,his death coincided with the collapse of hard bop artistically and economically(as music with a large enough audience to support it). And, of course, itdeprived the school of its star trumpet player.

Next page