PUBLISHED BY ALFRED A. KNOPF

All rights reserved.

Published in the United States by Alfred A. Knopf, a division of Random House LLC, New York, and in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto, Penguin Random House companies.

Knopf, Borzoi Books, and the colophon are registered trademarks of Random House LLC.

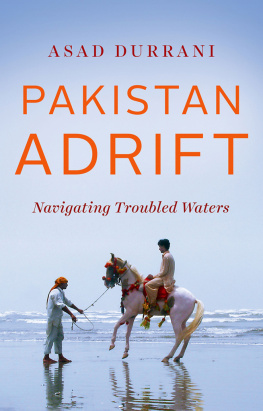

A man of good hope / by Jonny Steinberg. First edition.

This is a Borzoi bookT.p. verso.

ISBN 978-0-385-35272-7 (hardcover : alk. paper) ISBN 978-0-385-35273-4 (eBook)

1. Abdullahi, Asad. 2. SomaliaBiography. 3. RefugeesSomalia. 4. SomalisSouth AfricaBiography. 5. SomalisUnited StatesBiography. I. Title.

CT 2208. A 23 S 74 2014

Cover image: A view of Blikkiesdorp (Tin Can Town in Afrikaans) East of Cape Town, South Africa by Rodger Bosch/AFP/Getty Images

Preface

Asad Abdullahi sits opposite me at a table in the Company Gardens. Around us, elderly white men are playing chess.

My notebook is open on the table, my pen in my hand. I am asking Asad about the Kaaraan district of Mogadishu, where he spent the first eight or so years of his life. He says he remembers so little.

It doesnt matter, I say. Instead of trying to remember, just tell me what comes into your head when you think of Mogadishu.

The oddest thought comes to me. He is wearing a body-hugging yellow hoodie and skinny blue jeans, and, in this tight attire, he seems not just tall and thin, but elongated. Each part of himhis nose, his cheeks, his palms and his fingers, his torsoappears to have been ever so caringly stretched. The result is elegant.

It occurs to me that he is sitting at Cape Towns point of origin. The gardens around us were planted 358 years ago, almost to the day. Here is Asad, on very old ground, while he himself is so new and so decidedly unwelcome.

In his slender fingers is a twig. I think he found it while we were strolling up from the library. Now he snaps it in half and draws it to his nose.

His eyebrows rise with surprise. He smells it again.

Amazing, he says. From the moment I saw it lying on the ground, I knew what the smell would remind me of.

And he begins to tell me how he made ink. He was seven years old, he thinks, a student at a madrassa, preparing the charcoal mixture into which he would dip his pen in order to copy out the Koran. To bind the ink, he says, you need the sap of the agreeg tree. You snap open a branch and with pinched fingers tease out the juice, allowing it to drip into the charcoal and water. While stirring the mixture, you absentmindedly put your fingers to your nose. You breathe in deeply. Ah!

The smile on his face is wistful and intense, and I think I have an inkling of where he has gone.

He knows that I am still here, that, at the table next to us, men are playing chess. But he is also elsewhere, and he is savoring it, for he understands that it can last only a few seconds. He has reeled back more than twenty years. With the twig he has found in the Company Gardens, he is reliving a forgotten high, for it is clear from the expression on his face that the sap of the agreeg is narcotic.

I feel a whim rising. I know that if I think about it, even for a moment, I will find a reason to back off, so I do not think about it. A man who idly snaps open a twig and is transported back so vividly, so powerfully, to another world is a man about whom I ought to write a book.

Several weeks earlier, I had driven out to his shack for breakfast. My diary records the day as September 24, 2010, a public holiday in South Africa. I was accompanied by Pearlie Joubert, a journalist, who had introduced us. I had had an idea for a very different book. I had asked Pearlie to introduce me to people who had fled Cape Town in the wake of South Africas surge of violence against foreign nationals in May 2008. I had wanted to compare this episode to events that had happened fifty years earlier.

Asad came out to greet us wearing a turquoise macawi knotted around his waist and dropping to his ankles. Pearlie had told me that he was twenty-seven years old. He seemed more than that to me, perhaps because I associated the macawi with middle age.

The shack into which he invited us was covered everywhere in folds of delicate cloth. A dozen or so of them hung from the ceiling at the edge of his bed, screening it from the rest of the room. The tin walls, too, were coated in cloth, their colors dark and mutedmaroons and deep greens. They dimmed the room, as if dusk were falling and nobody had turned on the lights. It was with a start that I noticed his wife. She was on a stool in the corner, her chubby face staring out from a head shawl that covered most of her cheeks.

Asad invited us to sit, then crouched over a Bunsen burner. He would make us a Somali breakfast, he announced: pancakes. The dough was at his side in a plastic bowl, and the pan on the stove sizzled with strips of meat and onions and peppers.

Asad lives in BlikkiesdorpTin Can Town, in English. It has been described as Cape Towns asshole, the muscle through which the city shits out the parts it does not want. Built by the city in 2007, it consists of sixteen hundred identical one-room structures laid out in sixteen identical square blocks. Erected to house people removed from homes they occupied illegally, it is a dump in which the citys evicted are mixed together. More than thirty kilometers from the center of Cape Town, it is separated from the citys economic heartland by a long and expensive taxi ride. It is the ultimate ghetto, its residents hemmed in by distance, by poverty, and by their own personal histories.

In early 2010, the city and the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees decided, in their collective wisdom, to place thirty-four Somali and Congolese families in Blikkiesdorp. All had had to flee their homes in May 2008 with South African mobs at their heels. Each had spent the better part of the previous two years in makeshift refugee camps, too afraid to enter Cape Town again. Blikkiesdorp was the site of their reintegration. They could live rent-free in one-room shacks surrounded by the citys outcasts, people who could only hate them.