HOW TO BE A BAD EMPEROR

ANCIENT WISDOM FOR MODERN READERS

How to Be a Bad Emperor: An Ancient Guide to Truly Terrible Leaders by Suetonius

How to Be a Leader: An Ancient Guide to Wise Leadership by Plutarch

How to Think about God: An Ancient Guide for Believers and Nonbelievers by Marcus Tullius Cicero

How to Keep Your Cool: An Ancient Guide to Anger Management by Seneca

How to Think about War: An Ancient Guide to Foreign Policy by Epictetus

How to Be Free: An Ancient Guide to the Stoic Life by Epictetus

How to Be a Friend: An Ancient Guide to True Friendship by Marcus Tullius Cicero

How to Die: An Ancient Guide to the End of Life by Seneca

How to Win an Argument: An Ancient Guide to the Art of Persuasion by Marcus Tullius Cicero

How to Grow Old: Ancient Wisdom for the Second Half of Life by Marcus Tullius Cicero

How to Run a Country: An Ancient Guide for Modern Leaders by Marcus Tullius Cicero

How to Win an Election: An Ancient Guide for Modern Politicians by Quintus Tullius Cicero

HOW TO BE A

BAD EMPEROR

An Ancient Guide

to Truly Terrible Leaders

Suetonius

Selected, Translated, and Introduced by

Josiah Osgood

PRINCETON UNIVERSITY PRESS

PRINCETON AND OXFORD

Copyright 2020 by Princeton University Press

Requests for permission to reproduce material from this work should be sent to permissions@press.princeton.edu

Published by Princeton University Press

41 William Street, Princeton, New Jersey 08540

6 Oxford Street, Woodstock, Oxfordshire OX20 1TR

press.princeton.edu

All Rights Reserved

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Suetonius, approximately 69-approximately 122, author. | Osgood, Josiah, 1974- translator. | Suetonius, approximately 69-approximately 122. De vita Caesarum. Selections. English | Suetonius, approximately 69-approximately 122. De vita Caesarum. Selections.

Title: How to be a bad emperor : an ancient guide to truly terrible leaders / Suetonius ; selected, translated, and introduced by Josiah Osgood.

Description: 1st. | Princeton : Princeton University Press, 2020. | Series: Ancient wisdom for modern readers | Includes bibliographical references and index. | In English and Latin.

Identifiers: LCCN 2019026869 (print) | LCCN 2019026870 (ebook) | ISBN 9780691193991 (hardback) | ISBN 9780691200941 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: EmperorsRomeBiographyEarly works to 1800. | RomeHistoryEmpire, 30 B.C.-476 A.D.

Classification: LCC DG277.S7 O84 2020 (print) | LCC DG277.S7 (ebook) | DDC 937dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019026869

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2019026870

British Library Cataloging-in-Publication Data is available

Editorial: Rob Tempio and Matt Rohal

Production Editorial: Sara Lerner

Text and Jacket Design: Pamela Schnitter

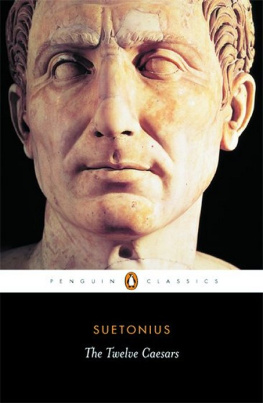

Jacket Credit: Bust of Caligula (Gaius Julius Augustus Germanicus), AD 1241, 3rd Roman emperor. Rome, AD 3741. Marble.

Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Copenhagen. (Photo by PHAS/Universal Images Group via Getty Images)

CONTENTS

INTRODUCTION

As president in the White House, a man becomes himself, squaredhis hyperself, flaws and virtues enlarged by world attention and brought to fulfillment by the nature of the work and the power, and by the inescapability of the buck that stops on the desk in the Oval Office. So journalist Lance Morrow has argued, in the introduction to a book about three American presidents, John F. Kennedy, Lyndon B. Johnson, and Richard M. Nixon. The Roman biographer Gaius Suetonius Tranquillius, though he could not have known about the White House or Oval Office, and could not have understood the buck that stops, would have found himself in firm agreement with Morrows basic point.

As the selections included in this book show, Suetonius believed that once in power, the emperors of Rome felt free to indulge their own passions and pursuits, no matter how weird or reckless. The moment Nero became emperor, Suetonius writes, he summoned the lyre-player Terpnus, considered the best at the time, and for days on end sat by him after dinner as he sang late into the night. Soon enough, he wished to drive chariots himself.

Power unmasked the true identity of emperors. It brought to light quirks and vices that, as Suetonius saw, make for fascinating reading. In his biography of Tiberius, we see the emperor retreat to the beautiful and isolated isle of Capri, where it was easier to ignore public affairs and give free rein to all of the vices that he had badly concealed for so long.

Although he was writing about emperors, Suetonius was determined to provide more than a rehashing of major historical events. He wanted readers to see what emperors were really like, in private as well as in public. So he tells the famous story of Julius Caesars brutal murder on the Ides of March. But he also tells us about Caesars dining habits and sex life, his physical health and appearance. Small observations matter: Caesar was always irritated by his baldness, because he could be mocked for it, and he was thrilled when he was voted the right to wear a laurel crown on all occasions. Before then, he had been forced to rely on a comb-over. Readers have fun with juicy details like these. They make Caesar seem like a real person. They also help us to grasp Caesars arrogance and vanity, and understand how those qualities ultimately led to his catastrophic end.

The way Suetonius organized his lives helped him to avoid recreating standard histories. While he does typically start with an emperors family background, birth, and life up to the point of gaining power, and end with the emperors death and the omens foretelling it, the central part of each biography is organized not chronologically, but topically. In this main section, Suetonius might talk about the emperors public policy, his games and shows, and his building projects; but also, after that, his family and friends, his sense of humor and hobbies, his religious practices, and his health, appearance, even sleep habits; and then, too, his arrogance and disrespectfulness, his cruelty, his sexual excesses, his extravagance and greed. This allowed Suetonius to showcase details that might be hard to fit into a linear narrative. Moreover, the Lives of the Caesars include altogether twelve emperors, beginning with Julius Caesar (Caesars successor Augustus nowadays is more commonly regarded the true first emperor) and ending with Domitian. Thus the reader can easily compare one emperor to another, and see similarities and differences. While the bad emperors featured in this bookJulius Caesar, Tiberius, Caligula, and Nerohave much in common, Caligula emerges as far worse than Tiberius. Tiberius at least tried to hide his cruelty; Caligula wanted to flaunt it.

For all the care with which he collected and catalogued details of emperors lives, Suetonius was not aiming for an objective presentation. He is not afraid to include what he knew were only rumors. There was... a set of rumors, Suetonius writes, that Caesar was going to move to Alexandria or Troy, taking all of the empires money with him. Such vivid images, even when identified as hearsay, stamp themselves on readers minds. They are almost the equivalent of modern political cartoons.

Next page