MOOMIN-GALLERY

I am Moominpappa, but of course, you all know me by now. Here I am in pensive mood I wish I knew where that hat disappeared to.

This is Sniff, one of Moomintrolls young friends. A little clumsy sometimes, but means well. After all the Muddler was his father.

A solitary chap, young Snufkin. Quite unlike the Joxter, his father, but with the same independent outlook on life.

I dont quite know what the Groke is doing here. She isnt much use for anything except as an exclamation!

Ha! here is the would-be-philosopher, our old friend the Muskrat, who likes to be left in peace to think at least that is what he wants us to believe he is doing.

These two are apt to turn up anywhere. Thingummy and Bob mischievous pair, too fond of pea-shooters and such; but I was young once.

The feminine touch. The Snork Maiden has taken a fancy to Moomintroll, but look what he did for her. Now I remember when I was a boy

But to proceed. Moomintroll now there is a chip off the old Moominblock if you like. An eternal reminder of my youth

As for the Hemulen why do they wear so much clothing? Must remember to look that up he is our leading Moominphilatelist and also sound on Moominchology.

So, if you want to read more about these curious but likeable inhabitants of Moominland, you should look at the list of books at the front. I wrote the notes above in 1952, how time goes, and have now added a few more opposite.

Misabel we met that curious summer. How she enjoyed acting in my plays, and changing clothes.

A tremendous big fellow that Hemulen who invaded the valley one winter. One of those terrific do-gooders. Hmm bit noisy.

Ah, Too-ticky much addicted to bathing-houses, the sea-side in every particular in fact, and quite a philosopher in a way.

No selection would be complete without Little My. What would we do without her imperturbability good word, what! good girl, good-bye for now.

me, boredom when you ought to enjoy yourself is the worst kind of boredom.

I went and called on the hedgehog.

Well? she said. Only dont say a word about Hemulens.

No, no, I said. But wont you come and look at my house? We could sit there for a while and have a chat. Ill tell you all about my strange birth.

That would be fascinating, said the hedgehog. Im so sorry I havent got the time. Im making milk-bowls for all my daughters.

And that went for all the people in the wood. The birds, the worms, the tree-spirits, and the mousewives seemed to be in a great hurry about something or other. Nobody wanted to look at my house, or hear about my escape, or about the strange way I came into the world.

I went back to my green garden by the brook and sat down on the verandah. My verandah. My lonely fretwork verandah.

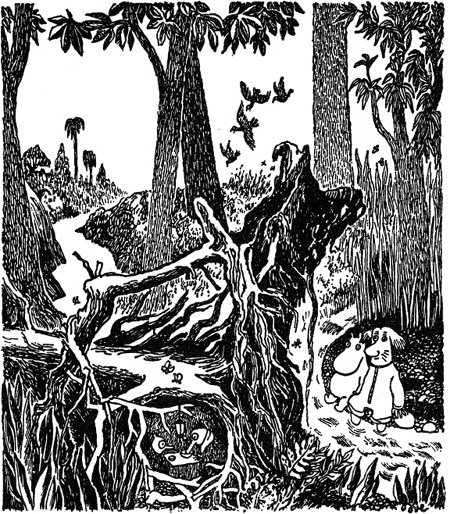

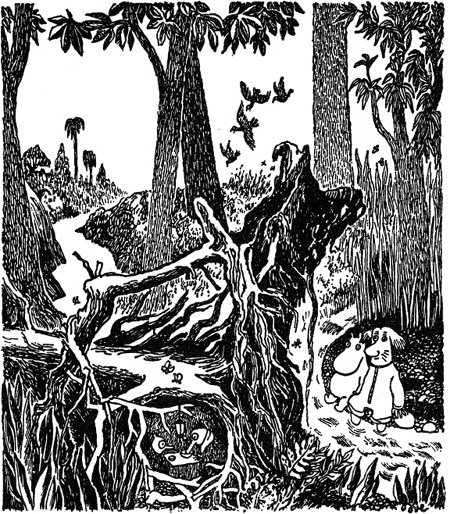

And suddenly click I had a new idea: to find out where the brook led.

I stepped into the cool water and began wading downstream. The brook ran as brooks do; with many freaks and

no hurry. Sometimes it rippled along, clear and shallow, over lots and lots of pebbles, and sometimes the water darkened and rose up to my snout. There were blue and red water-lilies floating everywhere in the stream. The sun was already setting and shone straight in my face. And after a while I began to feel almost happy again.

Then I heard a funny little whirring noise. Straight in front of me a splendid water-wheel was spinning. It was made of small sticks and stiff palm-leaves.

And somebody said: Please be careful.

I looked up and saw a couple of hairy ears in the long grass by the brook.

Im just looking, I said. Who are you?

Hodgkins, said the owner of the ears. And you?

The Moomin, I said. A lonely refugee born under rather special stars.

What stars? asked Hodgkins, and his question made me very happy, because it was the first time anybody had asked me something I wanted to answer.

So I went to the shore and sat down at his side, and there I told him everything that had happened to me since the day I was found in the newspaper parcel. (Only I told him it had been a small basket of leaves.) And all the time the water-wheel was spinning in a little cloud of glittering waterdrops, and the sun reddened and sank, and my heart found new peace and happiness.

Strange, said Hodgkins when I had finished. Rather strange. That Hemulen. Bit of a cad, I think.

Quite, I said.

Not many worse, are there? said Hodgkins.

Certainly not, I said.

Then we were silent for a while and looked at the sunset.

It was Hodgkins who showed me how to construct a water-wheel, an art that I have later taught my son. (Cut two forked branches and stick firmly in stream. Sandy bottom is best. Choose four stiff leaves, cross to form a star, pierce with stick. Strengthen construction with twigs. Carefully place stick on forks, and wheel will turn.)

In the evening twilight Hodgkins and I walked back to my house and I asked him in.

He said it was a good house. (Thereby he meant that it was a wonderful and fascinating house. Hodgkins never cared much for big words.) The night wind came and sang us a song.

I had now found my first friend, and so my life was truly begun.