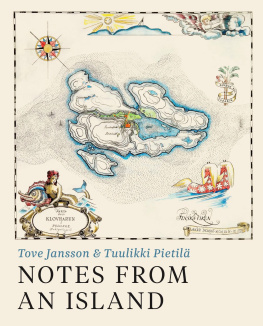

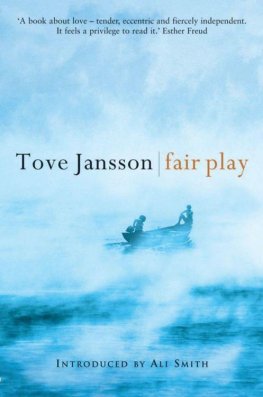

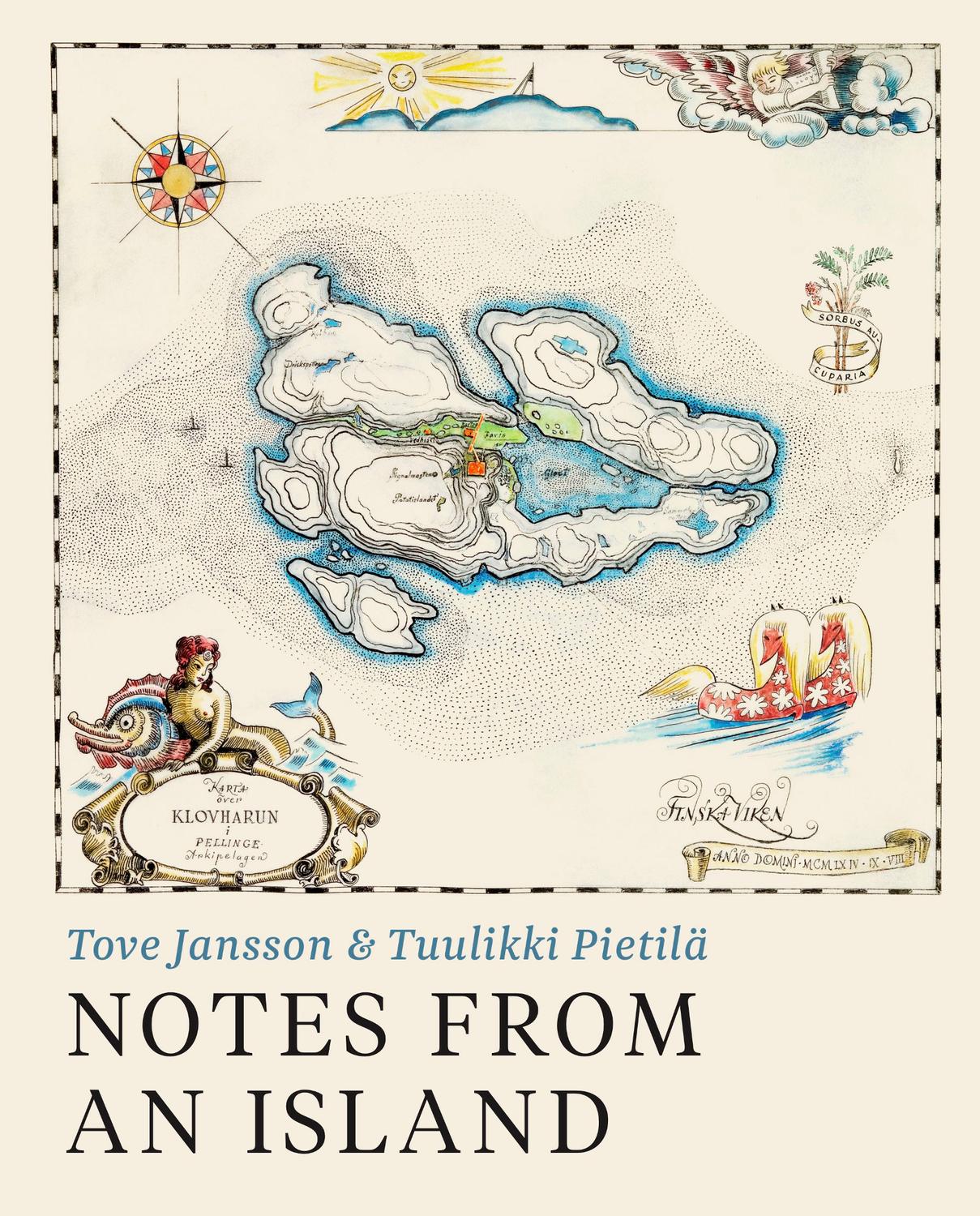

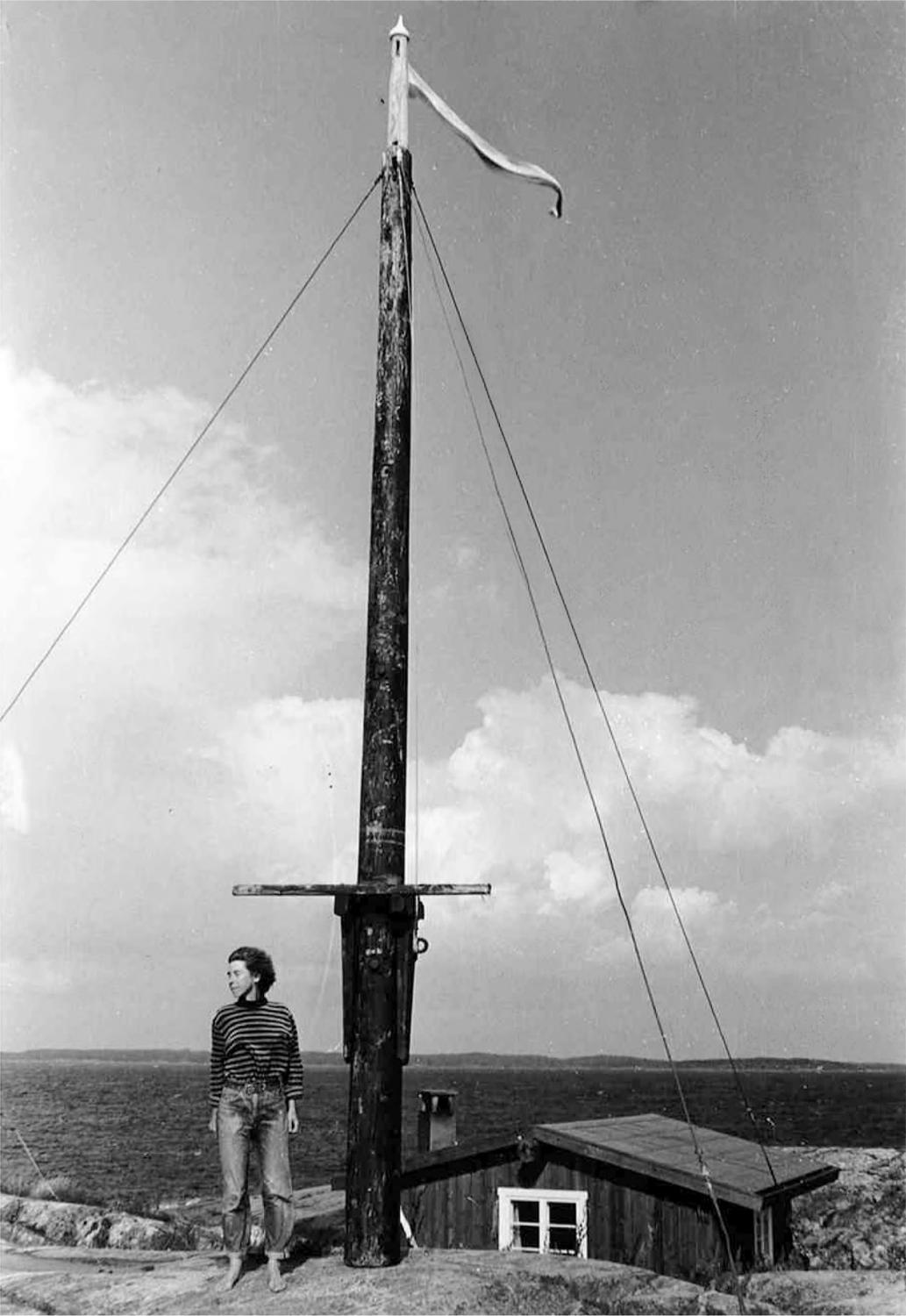

But, as Tove and Tooti reached their mid-seventies, the confidence they needed to thrive in such a harsh environment began to ebb and the exhilaration they had felt at storms and rough seas gave way to unease. A system of signals was arranged a raised flag or a call on the walkie-talkie to reassure those on Bredskr that all was well. However, they knew their last summer was approaching and told each other they would relinquish the island before age and anxiety forced the issue. In 1991, they signed a gift deed so the cabin could be used by hunters and fisherfolk, pinned up notices explaining its quirks, and left. They would never return. Indeed, such was the grief of separation that it would take nearly four years for Tove to allow herself to discuss Klovharun, and to begin the unique collaboration that would lead to Notes from an Island.

The kernel of this book (first published in Swedish in 1996) are the twenty-four copperplate etchings and wash drawings of Klovharun that Tooti completed in the 1970s. Their calm, meditative impact would be reflected in Toves prose, written as diary entries, lists and vignettes, and winnowed to ensure that not a single inessential phrase appears. Added to these are extracts from a logbook sent to Tove by Brunstrm, a man so laconic that he uses no adjectives in everyday speech (he is portrayed as Eriksson in The Summer Book). The whole is a moving homage to a tiny, rugged island and to a profound and enduring relationship.

I love rock sheer cliffs that drop straight into the ocean, unscalable mountain peaks, pebbles in my pocket. I love prising stones out of the ground, heaving them aside and letting the biggest ones roll down the granite slope into the water! As they rumble away, they leave behind an acrid whiff of sulphur.

Searching for building stones or just for pretty rocks to make mosaics, bulwarks, terraces, supports, smoke ovens, strange unusable structures made just for the sake of constructing, and for making piers which the sea will carry away next autumn and which Ill rebuild better for the sea to carry away all over again.

I am a sculptors daughter, but Tootis papa was a carpenter, so she loves wood, whether shes working with beautiful, heavy lumber or playing with featherweight balsa. We searched for juniper in the woods. Along the shore we managed to find unfamiliar hardwoods with unknown names. From these, Tooti carved the kinds of tiny objects that take time and infinite patience for example, the smallest salt spoon ever made.

But, says Tooti, when youre building big, thats completely different. You need determination and total confidence in your ability to estimate and measure and get things right, down to the centimetre. No, to the millimetre.

Sometimes we build things to be solid and lasting, and sometimes to be beautiful, sometimes both.

Incidentally, Tooti does her wood engravings in beech or pear and her woodcuts mostly in birch.

She often discussed materials with Albert Gustafsson in his boat shed in Pellinge; they also talked about boats. He gave her some small pieces of teak and mahogany to play with, and Tooti took them home and came up with some totally new ideas.

It was Albert who built our boat, in 1962, of mahogany, four metres long, clinker-built. It was the prettiest boat anyone had ever seen along that whole part of the coast. She was strong and agile and positively danced on the waves. Her name was Victoria, because both Tootis father and mine were named Viktor.

Later, as the summers passed, Victoria became more and more Tootis boat because she loved it the most and lavished care and attention on it.

There are many words for island isle, skerry, holm, reef, atoll, key.

The coastal charts for Pellinge archipelago show a crescent of uninhabited skerries west of Glosholm, perhaps the result of a capriciously formed ridge down on the sea floor. Kummelskr is the largest and prettiest pearl in this necklace.

I was still very young when I decided Id be the lighthouse keeper on Kummelskr. Granted, the only thing out there was a blinker beacon, but I was going to build something much bigger, a lighthouse so tall that I could see and watch over the whole eastern Gulf of Finland that is, when I grew up and was rich.

Gradually my dream of the unattainable changed and became a game with the feasible, and eventually merely a stubborn, irritated refusal to give up, until finally the Fishing Association told me in so many words that I was going to distress the salmon, so that was the end of that. But about two and a half nautical miles from Kummelskr, in towards the coast, there were some small islands that no one really cared about. One of them was Bredskr, and it was available for leasing.