Contents

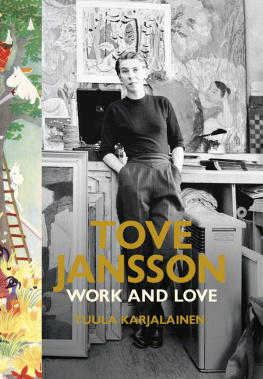

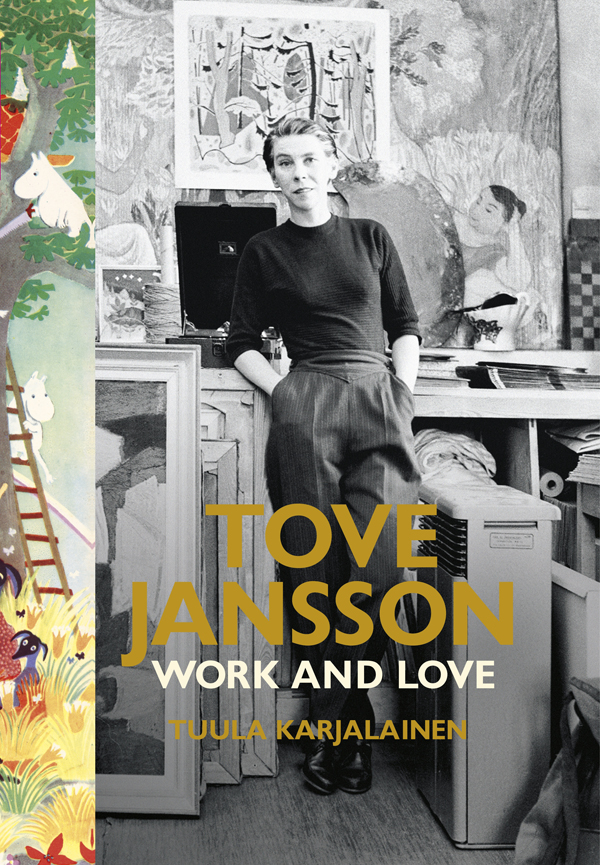

Tuula Karjalainen

TOVE JANSSON

Work and Love

Translated by David McDuff

PARTICULAR BOOKS

Published by the Penguin Group

Penguin Books Ltd, 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

Penguin Group (USA) Inc., 375 Hudson Street, New York, New York 10014, USA

Penguin Group (Canada), 90 Eglinton Avenue East, Suite 700, Toronto, Ontario, Canada M4P 2Y3 (a division of Pearson Penguin Canada Inc.)

Penguin Ireland, 25 St Stephens Green, Dublin 2, Ireland

(a division of Penguin Books Ltd)

Penguin Group (Australia), 707 Collins Street, Melbourne, Victoria 3008, Australia (a division of Pearson Australia Group Pty Ltd)

Penguin Books India Pvt Ltd, 11 Community Centre, Panchsheel Park, New Delhi 110 017, India

Penguin Group (NZ), 67 Apollo Drive, Rosedale, North Shore 0632, New Zealand (a division of Pearson New Zealand Ltd)

Penguin Books (South Africa) (Pty) Ltd, Block D, Rosebank Office Park, 181 Jan Smuts Avenue, Parktown North, Gauteng 2193, South Africa

Penguin Books Ltd, Registered Offices: 80 Strand, London WC2R 0RL , England

www.penguin.com

First published in Finnish as Tove Jansson: Tee Tyt ja Rakasta by Tammi 2013

First published in Great Britain by Particular Books 2014

Copyright Tuula Karjalainen, 2013

Translation copyright David McDuff, 2014

The moral right of the author and the translator has been asserted

Particular Books gratefully acknowledges the financial assistance of FILI (Finnish Literature Exchange) for this translation.

All rights reserved

ISBN: 978-1-846-14849-1

TUULA KARJALAINEN is a Finnish art historian and art critic and historian who has previously worked as director of the Helsinki Art Museum and the Kiasma Museum of Contemporary Art. She is the author of the books Uuden kuvan rakentajat: Konkretismin lpimurto Suomessa (Concretism in Finland), Ikuinen sunnuntai: Martta Wendelinin kuvien maailma (a study of the work of the Finnish painter Martta Wendelin), and Kantakuvat: Yheteinen muistimme (a study of ten well-known Finnish works of art).

THE BEGINNING

Let the conversation begin...

Follow the Penguin Twitter.com@penguinukbooks

Keep up-to-date with all our stories YouTube.com/penguinbooks

Pin Penguin Books to your Pinterest

Like Penguin Books on Facebook.com/penguinbooks

Find out more about the author and

discover more stories like this at Penguin.co.uk

To the Reader

The child moved for the first time. Just a small kick, but one clearly felt through the abdominal wall, and it sent a message I am me. Tove Janssons mother, Signe Hammarsten-Jansson, was out walking in Paris, and had just arrived at rue de la Gat Street of Joy. Was it a portent? Did it mean the child would be happy? At any rate, she would bring an enormous amount of joy to the world.

Times were hard. The threat of war hovered over Europe like the oppressive, stagnant air that precedes a thunderstorm. Despite, or perhaps just because of this, life in the art world was intense. Early twentieth-century Paris saw the birth of modern art Cubism, Surrealism and Fauvism and the city was home to writers, composers and artists whose names would soon become guiding stars. These included Pablo Picasso, Georges Braque, Salvador Dal and many others. Among them were Viktor Jansson from Finland and Signe Hammarsten-Jansson from Sweden, who had only been married a few months and their as yet unborn daughter. The First World War had already broken out when Tove Jansson was born in Helsinki on 9 August 1914.

In writing a biography you inevitably enter another persons reality and begin to live in a kind of parallel universe. Stepping into Tove Janssons life has been a rich and wonderful experience, though I had constantly to be aware that I might not necessarily be welcome. Tove has been the subject of biographies, studies and dissertations written from many different points of view. She permitted it during her lifetime, despite not always being very interested. She usually said that if one was going to write about an author it would be better to wait until he or she was dead, if at all. Yet it is also clear that she prepared for future researchers, as she preserved most of her extensive memoirs, correspondence and notebooks.

I met Tove once, in 1995. By then she was already eighty-one. I was preparing an exhibition about the artist Sam Vanni, who had died a few years earlier, and I was interested in the years that Tove and Sam had shared in the 1930s and 40s. For me, too, Vanni was a very dear and close friend whose work had formed the basis of my doctoral dissertation a few years earlier. I feared that Tove would have neither the time nor the strength for a meeting, but she wanted to see me. We sat in her turret studio in Ullanlinna and talked about art, life and Sam Vanni. Tove told me about their youth, about Maya Vanni and their visit to Italy, and about Sams teaching methods, and their friendship. I received answers to my questions, and for the exhibition catalogue Tove also promised to give us a story from her notebook that Sam then still Samuel Besprosvanni had told her. Suddenly Tove suggested that we take a little whisky. And so we drank whisky and smoked cigarettes, as people did in those decades. And the interviewee became the interviewer. Now I was able to tell her all about Sam, his wife and his sons, of whom Tove did not seem to know much at all. We realized that many other people who were important in Toves life had also touched mine. Of these, Tapio Tapiovaara was someone I knew quite well, and I had also met Tuulikki Pietil and Vivica Bandler many times.

The next time I was in Toves studio was when I was writing my book and studying her archive. For me, the most important items were her letters and notebooks. For months I sat alone in the Ullanlinna studio reading letters, as I couldnt copy them or remove them from the apartment. The studio still looked almost the same as it had done in Toves lifetime. Her self-portrait Lynx Boa (1942) gazed directly at me from the easel. On tables and windowsills were seashells and bark boats, and on the wall a gigantic library stretched from the floor high up to the ceiling, together with paintings stacked closely together. On the wall of the toilet there were pictures of disasters, sinking ships and stormy seas that Tove had cut out from various periodicals. It was all as it had been when she was alive. Her presence could be clearly felt.

There were a great many letters, which Tove had written over some thirty years. The most important were those she had sent to her friend Eva Konikoff in the United States: a large stack of them, written on thin tissue paper in small handwriting that filled each page, some blacked out or even mutilated by wartime military censors. Evas letters were not there. In a strange way the letters particularly brought to life the 1940s, the war and subsequent recovery. They gave a sense of what the war felt like to a woman who at that very time should have been enjoying her youth, making a career and building the framework of her life. And how it felt when the war was over. In addition to Evas letters I was also given access to Toves notebooks and her correspondence with other people, especially her letters to Vivica Bandler and Atos Wirtanen, which have been important for my book. Many of her short stories are based on material from these letters and notebooks, often very directly.