This edition is published by PICKLE PARTNERS PUBLISHINGwww.picklepartnerspublishing.com

To join our mailing list for new titles or for issues with our books picklepublishing@gmail.com

Or on Facebook

Text originally published in 1930 under the same title.

Pickle Partners Publishing 2015, all rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system or transmitted by any means, electrical, mechanical or otherwise without the written permission of the copyright holder.

Publishers Note

Although in most cases we have retained the Authors original spelling and grammar to authentically reproduce the work of the Author and the original intent of such material, some additional notes and clarifications have been added for the modern readers benefit.

We have also made every effort to include all maps and illustrations of the original edition the limitations of formatting do not allow of including larger maps, we will upload as many of these maps as possible.

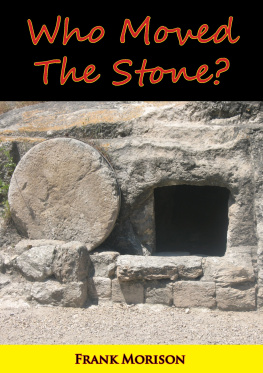

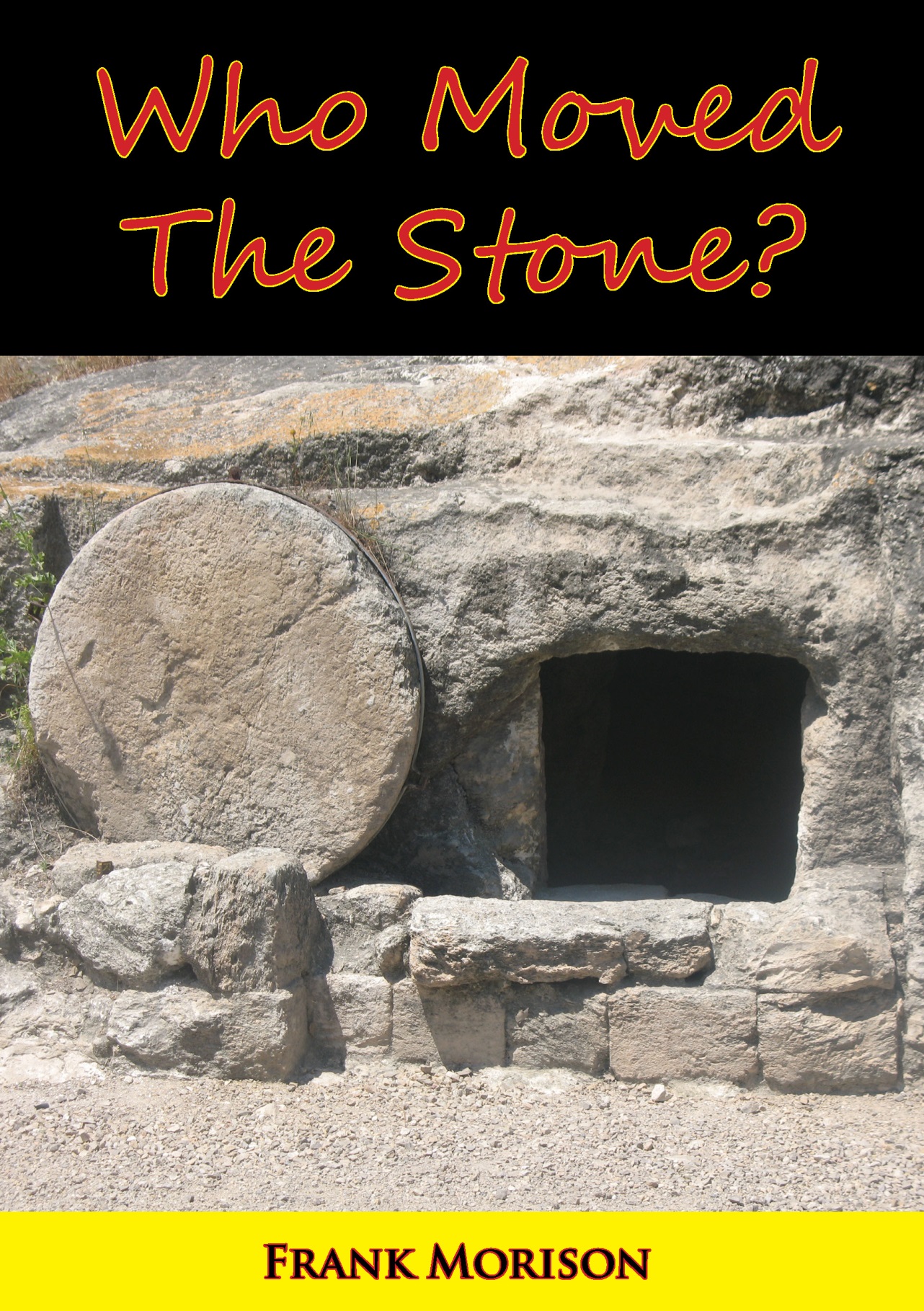

WHO MOVED THE STONE?

THE EVIDENCE FOR THE RESURRECTION

BY

FRANK MORISON

...Suffered under Pontius Pilate, was crucified, dead, and buried....The third day he rose again from the dead...

ABOUT THIS BOOK

It is not only a study on the Resurrection account as the title seems to suggest, but it retells the whole passion of Jesus Christ. Because the author does not concern himself with textual criticism, he is able to impress on the reader a consistent picture of the events of Passion and Resurrection. For this reason the book will perform a helpful service to everyone who wants a reconstruction of those events. Augustana Book News

A well-arranged summary of events relating to the resurrection of Christ and the pros and cons in the debate over their acceptance with emphasis on the latter. Watchman Examiner

The story Mr. Morison has told of the betrayal and the trial of Christ is fascinating in its lucid, its almost incontrovertible, appeal to the reason. For me, he made those scenes live with a poignancy and vividness that I have found in no other account, not even in the various attempts that have been made to present the same facts in the guise of a novel.J. D. Beresford

PREFACE

This study is in some ways so unusual and provocative that the writer thinks it desirable to state here very briefly how the book came to take its present form.

In one sense it could have taken no other, for it is essentially a confession, the inner story of a man who originally set out to write one kind of book and found himself compelled by the sheer force of circumstances to write quite another.

It is not that the facts themselves altered, for they are recorded imperishably in the monuments and in the pages of human history. But the interpretation to be put upon the facts underwent a change. Somehow the perspective shiftednot suddenly, as in a flash of insight or inspiration, but slowly, almost imperceptibly, by the very stubbornness of the facts themselves.

The book as it was originally planned was left high and dry, like those Thames barges when the great river goes out to meet the incoming sea. The writer discovered one day that not only could he no longer write the book as he had once conceived it, but that he would not if he could.

To tell the story of that change, and to give the reasons for it, is the main purpose of the following pages.

CHAPTER ITHE BOOK THAT REFUSED TO BE WRITTEN

I suppose that most writers will confess to having hidden away somewhere in the secret recesses of their most private drawer the first rough draft of a book which, for one reason or another, will never see the light of day.

Usually it is Timethat hoary offenderwho has placed his veto upon the promised task. The rough outline is drawn up in a moment of enthusiasm and exalted vision; it is worked upon for a time and then it is put aside to await that leisured tomorrow which so often never comes. Other and more pressing duties assert themselves; engagements and responsibilities multiply, and the treasured draft sinks further and deeper into its ultimate hiding-place. So the years go by, until one day the writer awakens to the knowledge that, whatever other achievements may be his, this particular book will never be written.

In the present case it was different.

It was not that the inspiration failed, or that the day of leisure never came. It was rather that when it did come the inspiration led in a new and unexpected direction. It was as though a man set out to cross a forest by a familiar and well-beaten track and came out suddenly where he did not expect to come out. The point of entry was the same; it was the point of emergence that was different.

Let me try to explain briefly what I mean.

When, as a very young man, I first began seriously to study the life of Christ, I did so with a very definite feeling that, if I may so put it, His history rested upon very insecure foundations.

If you will carry your mind back in imagination to the late nineties you will find in the prevailing intellectual attitude of that period the key to much of my thought. It is true that the absurd cult which denied even the historical existence of Jesus had ceased to carry weight. But the work of the Higher Criticsparticularly the German criticshad succeeded in spreading a very prevalent impression among students that the particular form in which the narrative of His life and death had come down to us was unreliable, and that one of the four records was nothing other than a brilliant apologetic written many years, and perhaps many decades, after the first generation had passed away.

Like most other young men, deeply immersed in other things, I had no means of verifying or forming an independent judgment upon these statements, but the fact that almost every word of the Gospels was just then the subject of high wrangling and dispute did very largely colour the thought of the time, and I suppose I could hardly escape its influence.

But there was one aspect of the subject which touched me closely. I had already begun to take a deep interest in physical science, and one did not have to go very far in those days to discover that scientific thought was obstinately and even dogmatically opposed to what are called the miraculous elements in the Gospels. Very often the few things the textual critics had left standing Science proceeded to undermine. Personally I did not attach anything like the same weight to the conclusions of the textual critics that I did to this fundamental matter of the miraculous. It seemed to me that purely documentary criticism might be mistaken, but that the laws of the Universe should go back on themselves in a quite arbitrary and inconsequential manner seemed very improbable. Had not Huxley himself declared in a peculiarly final way that miracles do not happen, while Matthew Arnold, with his famous gospel of Sweet Reasonableness, had spent a great deal of his time in trying to evolve a non-miraculous Christianity?

For the person of Jesus Christ Himself, however, I had a deep and even reverent regard. He seemed to me an almost legendary figure of purity and noble manhood. A coarse word with regard to Him, or the taking of His name lightly, stung me to the quick. I am only too conscious how far this attitude fell short of the full dogmatic position of Christianity. But it is an honest statement of how at least one young student felt in those early formative years when superficial things so often obscure the deeper and more permanent realities which lie behind.

Next page