Contents

Page List

Guide

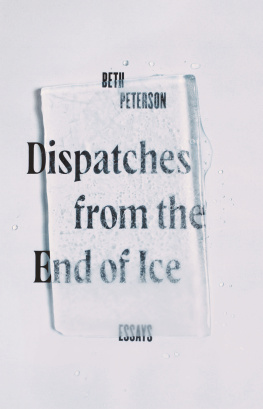

Dispatches from the End of Ice

Dispatches from the End of Ice

BETH PETERSON

TRINITY UNIVERSITY PRESS

San Antonio, Texas

Published by Trinity University Press

San Antonio, Texas 78212

Copyright 2019 by Beth Peterson

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without permission in writing from the publisher.

Book design by BookMatters

Cover design by ALSO

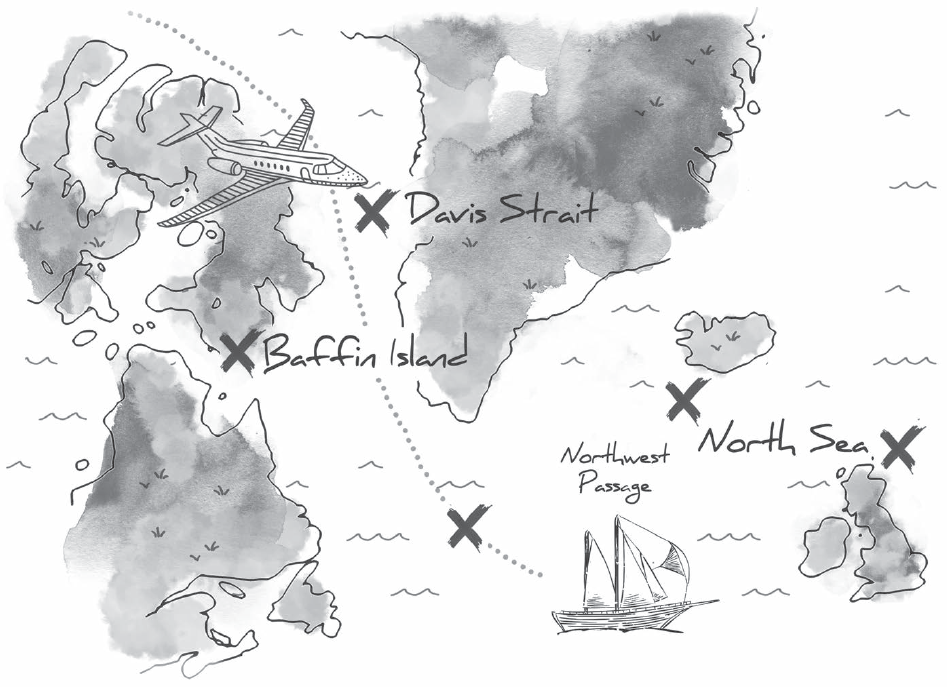

Maps and illustrations by Maya Blue

Author photo by Bobbie Peterson

Frontis: On July 12, 2011, the crew from the U.S. Coast Guard Cutter Healy retrieved a canister dropped by parachute from a C-130, which brought supplies for some midmission fixes.

NASA/Kathryn Hansen.

ISBN 978-1-59534-899-9 hardcover

ISBN 978-1-59534-900-2 ebook

Early versions of these essays were published in River Teeth (Glaciology), Passages North (Driving Wyoming), Newfound (Lost: An Inventory), The Pinch (Speed of Falling), the Ocean State Review (Baffin Island), Flyway (Theory of World Ice), the Mid-American Review (Wittgensteins Cabin), Terrain.org (Finding Atlantis), and Post Road (Journey to the Center of the Earth).

Trinity University Press strives to produce its books using methods and materials in an environmentally sensitive manner. We favor working with manufacturers that practice sustainable management of all natural resources, produce paper using recycled stock, and manage forests with the best possible practices for people, biodiversity, and sustainability. The press is a member of the Green Press Initiative, a nonprofit program dedicated to supporting publishers in their efforts to reduce their impacts on endangered forests, climate change, and forest-dependent communities.

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information SciencesPermanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI 39.48-1992.

CIP data on file at the Library of Congress

23 22 21 20 19 | 5 4 3 2 1

for Kate Northrop, Elizabeth Chang, and S. A. Stepanek

CONTENTS

BEFORE

BAFFIN ISLAND

THE AMERICAN MIDWEST

A few months after I leave the windswept plains of the Wyoming West for the last time, a flat, white document box comes for me in the mail. When I see the package resting against my front door, I will wonder for a moment if its an old passport finally returned or maybe my university diploma. I pick up the box and, still standing on the porchtall, narrow blades of bluegrass edging the boards, springing up through the wooden-slatted floorcarefully slide it open with a house key. Its not a passport, a diploma, or anything else Ive been waiting for. Instead, out of that box slips a small, hand-tipped map, dated 1750.

The map is of Norway, but not the Norway I know. There are no country boundaries between Norway, Sweden, and Finland, only lakes, mountain ranges, and rivers. Regions are separated by color and by tiny dots, bordering the edges. Letters in the place-namesBerghen, Gothland, Stavangerare fine and carefully printed, some closer together, some farther apart, the lengths and angle of es and ts varying based on their size and position. The sides of the map are crosshatched in black ink, but the rest of the map is painted in faded yellows, blues, and greens. Theres a water spot in one of the corners, then just above that, the name of the mapmaker, Robert de Vaugondy, and his own handwritten note in French with privilege.

For almost a year before that box arrived in the maila gift, it turns out, from my friend and former professor, KateId been thinking about maps. Id hung maps around the tall, white walls of my apartment; Id watercolor painted a five-foot-wide outline map of the world in vivid blues and purples; Id placed an old wooden globe that had once been my fathers in the center of my desk, traced its continents onto scraps of paper. Id even contacted an acquaintance from college who had become a cartographer and asked him if he could tell me how contemporary maps were made.

It had started with a question from a friend. I had intended to write a short collection of poetry in those days in Wyoming, but all my poems had been turning into scenes: nonfiction rescue scenes. At first, those scenes were traditional rescuesbystander saves boy from near-drowning in local lake; family of four and eleven cats escape house firebut gradually they had become stranger and more unrecognizable: deer jumps through back window of 1998 gold Toyota Tercel; mobile home blows off semi-truck bed in Virginia Dale, Colorado; two men struck by lightning under the same flowering willow. After reading a draft of one of these scenes, a friend had penned a single note on the bottom of my page. Where, he asked, is the rescue?

I read that note and then I read it again; I walked around, it seemed, for days, along the high mountain plain bordering the city where I lived, trying to pinpoint an answer to my friends question. I knew that with his where is the rescue? my friend was asking whether I was actually writing rescue scenes if the people in the scenes dont get rescued. In the end, though, it was the other part of that double-meaning where which always eluded me. The thing I needed to know was where; where in physical spacein what mapped placewould we be safe?

THE NORTHWEST PASSAGE

Norse mythology tells a story about a vast chasm and about a rescue. The chasm was famed to be the entrance from one world to the next, the exact spot where the earth originated and where, in the end of all days, it would disappear. As the tale goes, the cosmos was first made of three parts. To the north was the homeland of ice; to the south was the homeland of fire; and between them was a great gap called the Ginnungagap. Described by one writer as the chaos of perfect silence and by another as the yawning emptiness, the Ginnungagap represented nothingness: an immense primordial void.

Still, this void didnt stay empty forever. Over time, the land of ice and the land of fire began to move toward each other, gradually overtaking the Ginnungagap. Then, one fateful day, sparks from the land of fire and a frozen river from the land of ice finally met. The fires heat warmed the ice until there was frost and then melting frost, and then the melting frost transformed into a frost giant and into a cow; the cows milk was the giants food; the cows food was the salty ice.

It wasnt just ice though. Caught beneath all that ice was a man. That first day, as the cow licked the ice around her, the mans hair appeared. On the second day of licking her hot tongue against the frozen water, the mans head appeared. On the third day, the whole man was freed, cracked out of the ice like a nut from its casing. It was this man, Buri, whose great-grandsons would one day slay the giant, flinging forth from the giants frosted body the stars, the sky, and the earth as we know it.